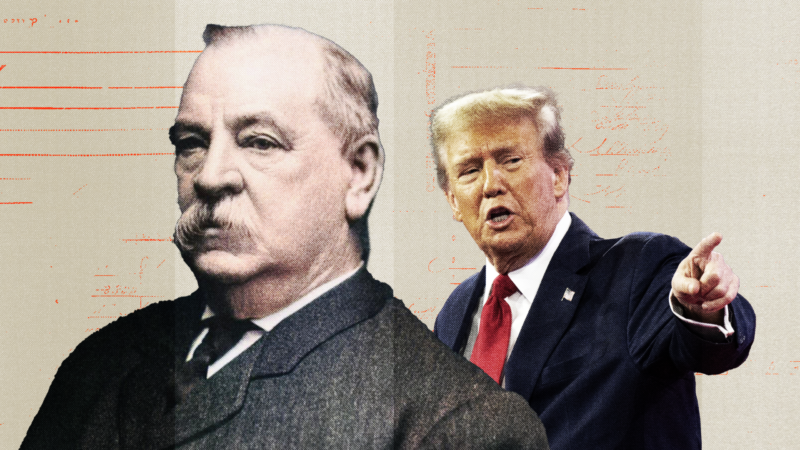

Trump vs. Cleveland: A Tale of Two Tariff Strategies

Grover Cleveland fought high tariffs as a “communism of pelf.” Trump embraces them as an economic cornerstone.

Donald Trump will soon become the second president to serve non-consecutive terms. Naturally, this invites comparison between Trump and the first president to serve non-consecutive terms, Grover Cleveland. In one crucial respect that juxtaposition is both instructive and cruelly ironic.

Trump has made raising tariffs a centerpiece of his economic agenda. Cleveland, by contrast, devoted his career to warning that high tariffs bring a specific and dangerous type of communism to America—a communism of pelf.

"Pelf" is a term for money acquired in a dishonest or dishonorable way, and while it may seem anachronistic, it is the perfect word to capture Cleveland's ideas. As he explained in a frustrated 1894 letter to Mississippi Rep. Thomas Catchings, "The trusts and combinations—the communism of pelf—whose machinations have prevented us from reaching the success we deserved, should not be forgotten nor forgiven." Yet his most consequential statement on tariff reform was a State of the Union message submitted to Congress on Dec. 6, 1887—exactly 137 years from the date of this article's publication.

Cleveland believed so strongly in tariff reform that, because of that State of the Union, he was able to dedicate his entire 1888 reelection campaign to the cause of lowering them. He lost that election in a controversial squeaker, but was decisively reelected in 1892 in no small part because economic events had vindicated his warnings.

When tariffs are too high, Cleveland argued, it means that corrupt politicians and businessmen are able to exploit consumers, often imposing severe hardships through price increases. Just as bad, it means that the government is failing to treat all citizens as equal before the law, instead picking winners and losers in the aforementioned "communism of pelf."

This was the situation that existed in America during and after the Civil War, when politicians imposed weighty tariffs under the pretext of supporting the nation's burgeoning business community. While American consumers initially accepted the additional taxation as a wartime necessity, the high rates persisted even after the nascent military-industrial complex had been wound down.

The problem was both simple and intractable: There were thousands of manufacturing, industrial, agricultural, and other business interests that profited from high tariffs. Each special interest group disregarded the national welfare to protect themselves, and as a result, the government accumulated massive surpluses—$113 million in 1886–1887 alone.

Despite this growing crisis, initially, Cleveland did not prioritize tariff reform. For the first two-and-a-half years after taking office in 1885, Cleveland concentrated on rooting out government corruption, which had reached such a nadir that in 1873 Mark Twain dubbed the post-Civil War era as a "Gilded Age." To the extent that Cleveland's anti-corruption agenda involved vetoing legislation he deemed financially wasteful, he indirectly picked off some of the rotten fruits that grew from the protectionist tree. However, it was not until 1887 that he shifted his attention to a need for sweeping tariff reform. When he did, he transformed the presidency and America in the process.

"Our progress toward a wise conclusion will not be improved by dwelling upon the theories of protection and free trade," Cleveland wrote in his message to Congress, alluding to the various nationalistic arguments made by the protectionists. "It is a condition which confronts us, not a theory." From there, Cleveland proposed moderate tariff reductions, focusing on increasing access to raw materials for ordinary consumers and adding the federal government's financial obligations could be met through internal revenue taxes levied on luxury items (particularly "tobacco and spirituous and malt liquors").

In the long term, the message was good news for America, as the 1887 State of the Union completely dominated national politics for the next year. In the process, Cleveland strengthened the office of the presidency, which had become weak in shaping policy in the more than two decades since the Civil War. Of equal importance, he raised awareness about a grave economic injustice. Finally, Cleveland gave the Democratic Party a new sense of identity after nearly a quarter-century of post-Civil War ennui. Democrats who did not support tariff reform were no longer viewed as proper Democrats; the same was true for Republicans but in reverse, as practically overnight they redefined themselves around the cause of protectionism.

In the short term, though, the message had negative results. Cleveland's tariff reform proposals passed the Democrat-controlled House of Representatives but failed in the Republican-controlled Senate. Even worse, despite winning the popular vote, Cleveland lost the 1888 election to Republican nominee Benjamin Harrison amid Electoral College disputes in the key states of New York and Indiana. (Unlike Trump, Cleveland accepted his defeat with grace and peacefully ended his term in 1889.) The Republicans took office and passed a high tariff law (framed by future president William McKinley, then an Ohio congressman). The McKinley tariffs raised the average duty on imports by almost 50 percent, and as Dartmouth University economist Douglas Irwin demonstrated in 1998, these tariffs did little to stimulate the economy even as they imposed considerable suffering on low-income Americans.

This is why, just like Trump, Cleveland was able to comfortably get elected to a non-consecutive term by promising to lower prices. The key difference is that, unlike Trump, Cleveland proposed an intelligent solution to the problem—lowering tariffs, not raising them.

Unfortunately for both Cleveland and the Americans of his time, he would not live to see his vision for tariff reform realized. America plunged into an economic depression shortly after he took office in 1893, compelling Cleveland to confront a number of unrelated crises before he could get to tariff reform. By the time a tariff bill did reach his desk in 1894, special interest groups in both parties had diluted it almost to meaninglessness. Cleveland couldn't bring himself to veto the Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act of 1894, and he only allowed it to become law without his signature. Adding insult to injury, McKinley and the Republicans politically benefited from the economic misery they'd helped cause, with Democrats getting blamed for the depression because of their incumbency and McKinley winning the 1896 presidential election in a major realignment.

Tariff reform along the lines Cleveland advocated would not become the law of the land until the Underwood-Simmons Act of 1913, which was promoted with far more political effectiveness by Woodrow Wilson, the first Democratic president to serve after Cleveland's administration. By then, Cleveland had been dead for five years.

Yet, Cleveland's tariff reform message was not a failure. In addition to putting himself on the right side of history, Cleveland offered a potent and timeless warning about the dangers of protectionism.

"When we consider that the theory of our institutions guarantees to every citizen the full enjoyment of all the fruits of his industry and enterprise, with only such deduction as may be his share toward the careful and economical maintenance of the Government which protects him, it is plain that the exaction of more than this is indefensible extortion and a culpable betrayal of American fairness and justice," Cleveland wrote. "This wrong inflicted upon those who bear the burden of national taxation, like other wrongs, multiplies a brood of evil consequences."

Show Comments (66)