A Psychedelic Ban Would Disrupt Important Research

Making DOI and DOC Schedule I drugs would interfere with psychiatric research.

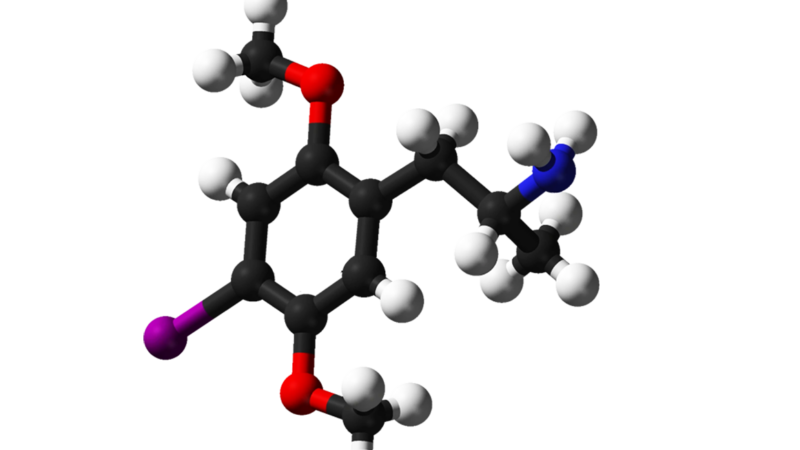

You have probably never heard of 2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine (DOI), much less worried about its possible abuse. Yet the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) wants to ban this synthetic psychedelic, a promising research chemical used in more than 900 published studies, by placing it in Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act. Students for Sensible Drug Policy (SSDP), which defeated a previous DEA attempt to ban DOI in 2022, is determined to stop the agency's interference with science again.

A DEA administrative law judge has scheduled a 10-day hearing on the proposed ban, beginning on November 12. SSDP, which filed a prehearing statement on behalf of more than 20 scientists, argues that placing DOI in Schedule I would impose "onerous financial and bureaucratic obstacles on researchers." SSDP also opposes the scheduling of another psychedelic, 2,5-dimethoxy-4-chloroamphetamine (DOC), under the same proposed rule, which the DEA published last December.

"DOI and DOC are important research chemicals with basically no evidence of abuse," says SSDP alum and legal counsel Brett Phelps. Phelps is working with Denver attorney Robert Rush, who represents University of California, Berkeley, neuroscientist Raul Ramos.

"The DEA's attempt to classify DOI, a compound of great significance to both psychedelic and fundamental serotonin research, as a Schedule I substance exemplifies an administrative agency overstepping its bounds," Rush says. "The government admits DOI is not being diverted for use outside of scientific research yet insists on placing this substance in such a restricted class that it will disrupt virtually all current research."

SSDP describes the two compounds as "essential research chemicals in pre-clinical psychiatry and neurobiology," noting that their unscheduled status has made them accessible as tools for studying serotonin receptors. It says DOI, in particular, has been "a cornerstone in neuroscience research" due to its selectivity for the 5-HT2A serotonin receptor, crucial for understanding the therapeutic effects of psychedelics. Scientists have used DOI to "map the localization of an important serotonin receptor in the brain critical in learning, memory, and psychiatric disease," SSDP notes, and DOI studies "have shown encouraging results in managing pain and reducing opioid cravings."

The DEA argues that DOI and DOC "have a high potential for abuse." While the two compounds "are available for purchase from legitimate chemical synthesis companies," the DEA concedes, "there is no evidence of diversion from these companies." But it notes that both drugs "have been encountered by law enforcement in the United States," indicating their "availability for abuse." Because "DOI and DOC are not found in FDA-approved drug products," the DEA says, people who use them must be doing so "on their own initiative, rather than based on medical advice."

Alluding to online accounts of DOI and DOC experiences on sites such as Erowid, the DEA notes "anecdotal reports" of individuals using these substances "for their hallucinogenic effects." From 2005 through 2022, the DEA's National Forensic Laboratory Information System (NFLIS) logged 40 reports of DOI and 790 reports of DOC. To put that in perspective, the NFLIS collected nearly 1.2 million drug reports in 2022 alone.

Renowned biochemist Alexander Shulgin described the synthesis and effects of DOI and DOC more than three decades ago. Yet the DEA offers no evidence that recreational use of them is common, let alone that it has caused widespread harm. "To date," the DEA admits, "there are no reports of distressing responses or death associated with DOI in medical literature." It does cite three published reports of adverse events linked to DOC between 2008 and 2015, including "seizures, agitation, tachycardia, hypertension, and death of one individual."

The DEA notes that "DOI and DOC share similar mechanisms of action" with "other schedule I hallucinogens," such as DOM, DMT, and LSD, and "produce similar physiological and subjective effects." It says they therefore "pose the same risks to public health." Although those risks, such as "hallucinogenic effects, sensory distortion, impaired judgment, [and] strange or dangerous behaviors," are mainly "borne by users," the DEA says, "they can affect the general public, as with driving under the influence."

The fact that the DEA counts "hallucinogenic effects" and "sensory distortion" as "risks" underscores its hostility toward psychedelics and its refusal to recognize their potential benefits. In assessing DOI's "potential for abuse," Phelps and Rush note, the DEA "does not distinguish between use and abuse."

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "A Psychedelic Ban Would Disrupt Important Research."

Show Comments (175)