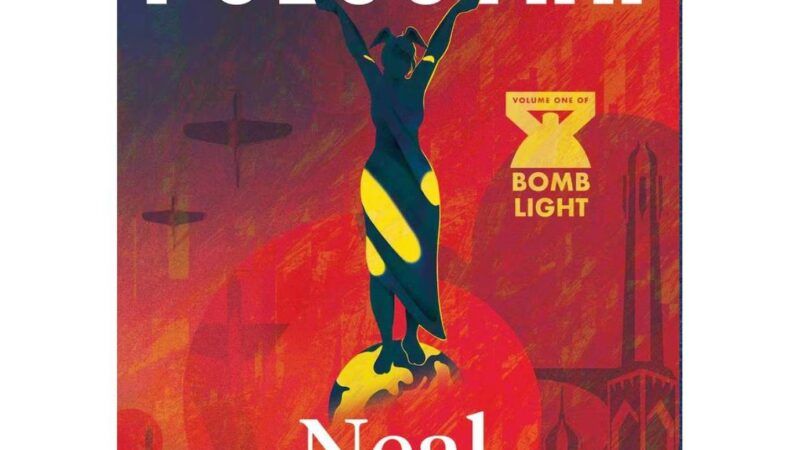

Neal Stephenson's Polostan Is a Compact Epic About Communism, Science, and the Dawn of the Atomic Age

A short-yet-sprawling historical tour of the atomic age.

Critics sometimes gripe that Neal Stephenson's sprawling, discursive, episodic, prop-up-your-laptop-sized novels may be smart, but they need focus and paring back. Too many of his novels have approached, or even run past, the thousand-page mark. In this view, he needs an editor, a groundskeeper, someone to trim his excesses and check his enthusiasm.

Yet part of the pleasure of a large, long Stephenson novel is the sheer expansiveness of his vision, the vastness of his imagination, the marvel of his world building, and the sly comedy he wrings from it. Stephenson's cinderblock-sized books are geeky odes to editorial noninterference.

Those critics might enjoy his latest novel, Polostan, which runs just over 300 pages, making it his shortest in decades. The book is lean and light, but it's far from slight. Even in its slimmed-down form, it retains Stephenson's sense of comedy and awe-struck enormity. Like a skinny person on Ozempic, Polostan still feels suspiciously like a much bigger book. It's a characteristically grand, Stephensonian vision, about the perils of Communism and the tumultuous glory of scientific progress. Or at the very least, it's part of one.

To some extent, the book's sense of scale is a result of the subject matter: Polostan is a story about the dawn of the atomic age.

Set largely in the 1930s, it sweeps across the Soviet Union and the United States in an era of momentous change. The Soviets have embraced a cruel and all-encompassing Communism. The United States is in the midst of its own political-social upheaval, with anarchists and agitators scattered across the country, plotting ideological victories and fomenting unrest. And in the background, the pace of scientific discovery and accomplishment is accelerating.

But it's also because of the way that Stephenson simply gravitates toward large-scale engineering projects and mechanical complexity. His most recent novel, Termination Shock, featured an extended sequence involving the Maeslantkering, a Dutch storm surge barrier that is one of the largest moving objects in the world; Snow Crash depicts a refugee camp nested in a massive boat network surrounding a decommissioned aircraft carrier. Seveneves closes with a depiction of a massive ring habitat and a hanging city that slowly circumnavigates the equator.

Stephenson has sometimes argued for optimistic, hopeful science fiction that inspires people to believe in a bigger, better, bolder future, one defined by human ingenuity and scientific accomplishment. So it is no surprise that his own stories tend to dwell at length on the imposing details of these infrastructure megaprojects, portraying them with fawning, nerdy awe. For Stephenson, bigger is almost always better—or at least more interesting to write about.

Polostan continues in this tradition, except that instead of inspiring readers through grandiose visions of the future, Stephenson wants to remind them of the scientific glories of the past that made our present possible. And so he treats the past as a sort of science-fictional setting, an unfamiliar world of great technological wonders, the dawn of modernity and scientific progress. The protagonist, amusingly, is a teenage girl named Dawn.

The prologue is set in San Francisco, a still-forming city on the water, with networks of ferries and cargo ships tacking back and forth along the waves, in the shadow of the not-yet-built Golden Gate Bridge. Another early chapter takes readers to a massive Soviet steel mill, giving readers a guided tour of the still-being-built facility and its complex operations. There's a long section set at the World's Fair in Chicago, with lengthy descriptions of seemingly every booth and technological wonder—including X-ray machines and zeppelins—on display. And there are extended descriptions of Moscow's labyrinthine streetcar network and the U.S. freight rail network, which served as an ad hoc public transportation system for an array of hobos, drifters, radicals, and activists. Stephenson is a master of describing complex built environments, the ways in which spaces and places become machines to move people and make things and generally contribute to the human project.

But Stephenson doesn't just see technology in simple builder's terms: He's also keen to explore the ways that technology shapes culture—or rather cultures, and the factions and subfactions that arise within them. Nearly every Stephenson novel is a story of some form of technologically mediated culture clash, of groups of people who respond to the forces of technology and history by choosing to live together in a specific way.

In Polostan, that clash revolves around Communist ideology and its various opponents, fractious offshoots, and second-order movements, like Wobblies, Bonus Workers, and anarcho-syndicalists. In Stephenson's worldview, socioeconomic systems and ideologies are, themselves, a kind of technology, a series of interlinked systems, like streetcar tracks and bridges, that make human activity possible—or, in some cases, impossible.

One of Polostan's recurring notions is just how bad Communism was at using human capital: The books shows how humans are abused, wasted, killed off, sent to work in brutal and thankless conditions on pointless projects, controlled by comfortable elites, tortured by government-employed psychopaths, and generally treated with disregard.

To Stephenson's credit, these scenes tend to be funny as well as horrific: The prisoners forced to build the sprawling Soviet steel mill are forced to play constant mind games with their dim-witted, paranoid party overseers.

One character, a highly credentialed Ukranian scientist who has been sentenced to work in the blast furnace gang, is granted a sort of grudging-yet-suspicious respect. The party minders know they can't quite afford to lose him—he keeps proving stubbornly valuable—but they have also subjected him to a life of physical and mental torture that undermines his talents. Stephenson's point is not only that it's incredibly inhumane, but that it's inefficient, a waste of a great mind and a great resource.

Stephenson's hero is the aforementioned Dawn, also known as Aurora, a plucky teenager raised in both America and the Soviet Union by a true-believing Marxist father and a rebellious anarcho-syndicalist mother.

Dawn is a Forest Gump-like figure, conveniently present at seemingly every pivotal moment in the United States and the USSR during the early 1930s, and much of the story consists of her attempting to explain herself to a KGB apparatchik. How is it that she speaks excellent Russian as well as English? How is it that she knows so much about tommy guns? How, exactly, does she know how to ride a horse and play polo?

The answers to these questions serve as the superstructure to the book's shaggy plot, which is mainly an excuse to explore the era and its techno-ideological underpinnings. Stephenson treats this period as both a playground of scientific wonders and an incubator of social change. It's a chaotic historical moment in which technology collided with ideology and birthed the modern world. And it's all in service of—well, presumably we'll eventually find out.

One of the reasons the book feels so much bigger than its tidy page count is that it's the start of a series, dubbed Bomb Light, with more books to come. It's hard not to wonder if this 300-odd page book is really just the introductory third of another thousand-ish page doorstopper broken into multiple parts, a teaser for what will eventually become a much more sprawling story.

Personally, I can't wait. Even the shortest and slightest of Stephenson's books are vast, intricate machines—bigger, better, and bolder than almost anything else you can read.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Well, his much earlier books - Diamond Age and Snow Crash (and Big U) were short, but I've said for a while that his books are 300 page novels with 600 pages of footnotes incorporated into the text.

This will deffo be added to my reading list.

It's pretty charitable to call 500 page books "short".

Too many of his novels have approached, or even run past, the thousand-page mark. In this view, he needs an editor, a groundskeeper, someone to trim his excesses and check his enthusiasm.

That's why I stopped reading him. He was my favorite author for a while back in the 90s with Snow Crash, The Diamond Age and Cryptonomicon. But then things just started getting... sclerotic.

He's a great writer but... Jesus. Get to the point, dude.

Anathem was fantastic. Seveneves was 50% good, and the last half was just terrible, despite the good ideas within. Fall was pretty tightly written and well paced.

Seveneves was 25% good. Stephenson's moderately intelligent and frequently ahead of the curve but the whole book is chock full of woke garbage that anybody with a passing familiarity with any of the topics who wasn't sucking off Stephenson, woke ideology, or both, would recognize as utter garbage.

If you replaced the second half of the book with a "Planet Of The Lesbians" erotic fiction, the first half of the story is ridiculous enough to support it without missing a beat.

Agree on Seveneves.

Mostly it was miserable. I liked the vision at the last part of the book, though. Seemed like a world worth exploring, rather than the overexplored first part of the novel.

My least favorite Stephenson.

Agree also with Overt. Anathem was fantastic.

Diane, If you liked the Diamond Age and Cryptonomicon, Anathem is worth a read. It’s not at all like the Baroque Cycle and a wonderful paeon to language as well as a cracking story. Good first person, unreliable narrator worthy of Nabakov or Gene Wolfe, a hint to the Glass Bead Game, and prescient as some of his work is. The notion of the internet being so full of bullshit that it is easy to find information, it very difficult to find ACCURATE information, was pretty well stated for 2008.

I liked Reamde, but it was long. He said he started with too many characters and had to wrap them all up. Fall, not a sequel so much as in the same universe, was also long but an interesting look at the concept of mortality and self determination. Probably not for people who gave up over books being too long, though.

Stephenson's hero is the aforementioned Dawn, also known as Aurora, a plucky teenager raised in both America and the Soviet Union by a true-believing Marxist father and a rebellious anarcho-syndicalist mother.

Stephenson going full girl-boss in this one?

How is it that she speaks excellent Russian as well as English? How is it that she knows so much about tommy guns? How, exactly, does she know how to ride a horse and play polo?

Girl boss. Eh, sorry Neal, pass.

Speaking of people like Harris and Charlamagne the God missing the woke meteor bursting into flames as it hit the atmosphere, searing and smashing right through everything as it slammed into the surface of the Earth, and leaving a smoldering hole where previously profitable businesses, franchises, and cultures had been like a massive socialist hammer; did you see that Victoria’s Secret rebooted its runway show?

Spoiler Alert: The new head honchos think the old head honchos who wanted diversity but were more focused on “What women want.” didn’t embrace body diversity, plus size and trans individuals, hard enough.

Yeah...I got too sick of it in Termination Shock and gave up. I was tired of a dude writing about what that horny queen needed and desired in conversing with her daughter. Gimme a break! Do mom's and daughters sit and cajole each other about their sexual needs?

I have read most of his other stuff...actually started with Snow Crash and didn't like it as much as it was hyped. Enjoyed pretty much all of the other stuff except I didn't try out Seveneves, yet.

When did you read Snow Crash?

Just because it was a novel of its time. Or ahead of its time. But its time was 30 years ago and all of that stuff wasn't so wild and didn't spark my imagination last time I reread it, but it definitely did in the early 90s.

>The Soviets have embraced a cruel and all-encompassing Communism

No, the Soviets *were* the cruel Commies. Sheesh.

And Polostan sounds like a rewrite of The Diamond Age.

And I see that the Baroque Cycle has been memory-holed, not that it doesn't well deserve it.

I enjoyed it, though, as with Simon Schama's non-fiction, he wears his learning heavily.

To which ‘Stan does Stevenson’s title refer?

Polo is alive , well and highly competitive in its Northern Areas strongholds in Pakistan, having survived Mao in China, and the Taliban in Afghanistan.

It may yet end up as a Superbowl sport , now that AI drones can chase the action at speed without scaring the horses.