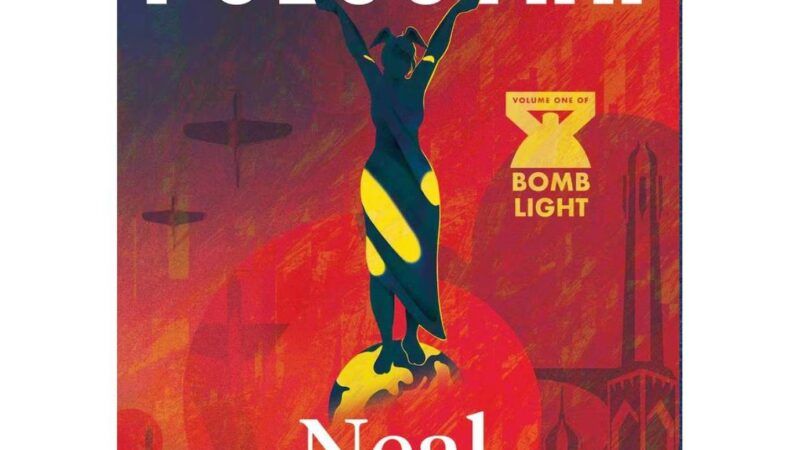

Neal Stephenson's Polostan Is a Compact Epic About Communism, Science, and the Dawn of the Atomic Age

A short-yet-sprawling historical tour of the atomic age.

Critics sometimes gripe that Neal Stephenson's sprawling, discursive, episodic, prop-up-your-laptop-sized novels may be smart, but they need focus and paring back. Too many of his novels have approached, or even run past, the thousand-page mark. In this view, he needs an editor, a groundskeeper, someone to trim his excesses and check his enthusiasm.

Yet part of the pleasure of a large, long Stephenson novel is the sheer expansiveness of his vision, the vastness of his imagination, the marvel of his world building, and the sly comedy he wrings from it. Stephenson's cinderblock-sized books are geeky odes to editorial noninterference.

Those critics might enjoy his latest novel, Polostan, which runs just over 300 pages, making it his shortest in decades. The book is lean and light, but it's far from slight. Even in its slimmed-down form, it retains Stephenson's sense of comedy and awe-struck enormity. Like a skinny person on Ozempic, Polostan still feels suspiciously like a much bigger book. It's a characteristically grand, Stephensonian vision, about the perils of Communism and the tumultuous glory of scientific progress. Or at the very least, it's part of one.

To some extent, the book's sense of scale is a result of the subject matter: Polostan is a story about the dawn of the atomic age.

Set largely in the 1930s, it sweeps across the Soviet Union and the United States in an era of momentous change. The Soviets have embraced a cruel and all-encompassing Communism. The United States is in the midst of its own political-social upheaval, with anarchists and agitators scattered across the country, plotting ideological victories and fomenting unrest. And in the background, the pace of scientific discovery and accomplishment is accelerating.

But it's also because of the way that Stephenson simply gravitates toward large-scale engineering projects and mechanical complexity. His most recent novel, Termination Shock, featured an extended sequence involving the Maeslantkering, a Dutch storm surge barrier that is one of the largest moving objects in the world; Snow Crash depicts a refugee camp nested in a massive boat network surrounding a decommissioned aircraft carrier. Seveneves closes with a depiction of a massive ring habitat and a hanging city that slowly circumnavigates the equator.

Stephenson has sometimes argued for optimistic, hopeful science fiction that inspires people to believe in a bigger, better, bolder future, one defined by human ingenuity and scientific accomplishment. So it is no surprise that his own stories tend to dwell at length on the imposing details of these infrastructure megaprojects, portraying them with fawning, nerdy awe. For Stephenson, bigger is almost always better—or at least more interesting to write about.

Polostan continues in this tradition, except that instead of inspiring readers through grandiose visions of the future, Stephenson wants to remind them of the scientific glories of the past that made our present possible. And so he treats the past as a sort of science-fictional setting, an unfamiliar world of great technological wonders, the dawn of modernity and scientific progress. The protagonist, amusingly, is a teenage girl named Dawn.

The prologue is set in San Francisco, a still-forming city on the water, with networks of ferries and cargo ships tacking back and forth along the waves, in the shadow of the not-yet-built Golden Gate Bridge. Another early chapter takes readers to a massive Soviet steel mill, giving readers a guided tour of the still-being-built facility and its complex operations. There's a long section set at the World's Fair in Chicago, with lengthy descriptions of seemingly every booth and technological wonder—including X-ray machines and zeppelins—on display. And there are extended descriptions of Moscow's labyrinthine streetcar network and the U.S. freight rail network, which served as an ad hoc public transportation system for an array of hobos, drifters, radicals, and activists. Stephenson is a master of describing complex built environments, the ways in which spaces and places become machines to move people and make things and generally contribute to the human project.

But Stephenson doesn't just see technology in simple builder's terms: He's also keen to explore the ways that technology shapes culture—or rather cultures, and the factions and subfactions that arise within them. Nearly every Stephenson novel is a story of some form of technologically mediated culture clash, of groups of people who respond to the forces of technology and history by choosing to live together in a specific way.

In Polostan, that clash revolves around Communist ideology and its various opponents, fractious offshoots, and second-order movements, like Wobblies, Bonus Workers, and anarcho-syndicalists. In Stephenson's worldview, socioeconomic systems and ideologies are, themselves, a kind of technology, a series of interlinked systems, like streetcar tracks and bridges, that make human activity possible—or, in some cases, impossible.

One of Polostan's recurring notions is just how bad Communism was at using human capital: The books shows how humans are abused, wasted, killed off, sent to work in brutal and thankless conditions on pointless projects, controlled by comfortable elites, tortured by government-employed psychopaths, and generally treated with disregard.

To Stephenson's credit, these scenes tend to be funny as well as horrific: The prisoners forced to build the sprawling Soviet steel mill are forced to play constant mind games with their dim-witted, paranoid party overseers.

One character, a highly credentialed Ukranian scientist who has been sentenced to work in the blast furnace gang, is granted a sort of grudging-yet-suspicious respect. The party minders know they can't quite afford to lose him—he keeps proving stubbornly valuable—but they have also subjected him to a life of physical and mental torture that undermines his talents. Stephenson's point is not only that it's incredibly inhumane, but that it's inefficient, a waste of a great mind and a great resource.

Stephenson's hero is the aforementioned Dawn, also known as Aurora, a plucky teenager raised in both America and the Soviet Union by a true-believing Marxist father and a rebellious anarcho-syndicalist mother.

Dawn is a Forest Gump-like figure, conveniently present at seemingly every pivotal moment in the United States and the USSR during the early 1930s, and much of the story consists of her attempting to explain herself to a KGB apparatchik. How is it that she speaks excellent Russian as well as English? How is it that she knows so much about tommy guns? How, exactly, does she know how to ride a horse and play polo?

The answers to these questions serve as the superstructure to the book's shaggy plot, which is mainly an excuse to explore the era and its techno-ideological underpinnings. Stephenson treats this period as both a playground of scientific wonders and an incubator of social change. It's a chaotic historical moment in which technology collided with ideology and birthed the modern world. And it's all in service of—well, presumably we'll eventually find out.

One of the reasons the book feels so much bigger than its tidy page count is that it's the start of a series, dubbed Bomb Light, with more books to come. It's hard not to wonder if this 300-odd page book is really just the introductory third of another thousand-ish page doorstopper broken into multiple parts, a teaser for what will eventually become a much more sprawling story.

Personally, I can't wait. Even the shortest and slightest of Stephenson's books are vast, intricate machines—bigger, better, and bolder than almost anything else you can read.

Show Comments (14)