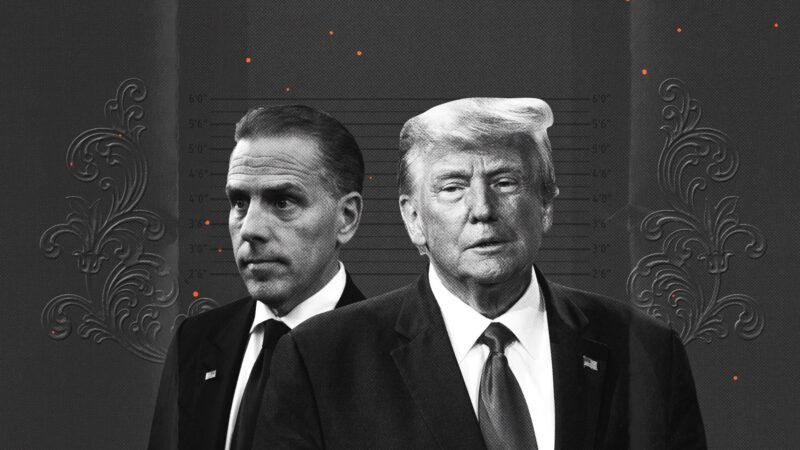

Donald Trump and Hunter Biden Are Both Felons. But What Does Felon Really Mean?

For hundreds of years, a felony has been defined not by the action itself but by how we punish it.

"Guilty," pronounced the May 31, 2024, Associated Press headline: "Trump Becomes First Former US President Convicted of Felony Crimes." Just 11 days later, The New York Times blazoned, "Jury Finds Hunter Biden Guilty of 3 Felonies." Regardless of what politicians and pundits performatively proclaim, Republicans and Democrats share some common ground.

The term felony derives from the Old French felonie, which meant wickedness or treachery. That in turn came from the Medieval Latin term felonia, with similar connotations, though with a melodious flow that could have placed it on the top baby names of 2023 beside Olivia, Amelia, Sophia, and Aria. The word's roots go further back to the Proto-Germanic word fel, which meant "to deceive" or "to betray." From its inception, the word has been associated with severe moral and ethical breaches.

The term began to take on its legal significance in medieval England. The first recorded legal use of felony appears in the Statute of Westminster (1275), enacted during the reign of King Edward I. The statute categorized felonies as crimes punishable by death or severe penalties, reflecting the feudal justice system where such trespasses were seen as grave offenses against the king's peace.

Use of the term hasn't changed much since the 13th century. Felonies are still defined not by the action itself but by how we punish it. In the United States, any offense punishable by death or more than one year's imprisonment is called a felony.

Before acquiring legal connotations, felon was a literary term. Even after it became a category for crimes, in the absence of legal guidance, people turned to sermons and stories for context. The earliest examples of the word in literature are "never about single acts; they are always about identifying what role the character will play in the story," said Elise Wang, an assistant professor at California State University, Fullerton, and the author of The Making of Felony Procedure in Middle English Literature, in a June workshop with the Modern Criminal Law Review. "If someone is called a felon, you know that they're the villain of the story [and] it's almost always about betrayal."

From feudal England to 21st century America, a felony has always had collateral consequences, including a social agreement that the perpetrator has forfeited a good life. Whether the felony is murder, theft, or decidedly modern violations such as fraudulently falsifying business records or lying on a form to purchase a firearm, all are grouped together and theoretically represent the gravest breach of our collective trust.

With an estimated 19 million Americans living with a felony charge—including an extremely disproportionate 33 percent of African-American males—it's worth reexamining this relic of a feudal society. Perhaps it's time to think harder about which behaviors are egregious enough to render those who commit them forfeit of a good life. Indeed, having no king with whose peace we must be concerned, perhaps it's time we consider our own.

Show Comments (94)