Does Your State Let You Work Without Government Permission?

A new report ranks the states on their occupational licensing requirements.

Some of the worst barriers to starting businesses, changing jobs, or moving from one state to another are occupational licensing requirements. The need to get permission from the government to work protects existing practitioners at the expense of those trying to enter trades and professions. That reduces competitive pressure that could improve quality and lower prices. If you're trying to maneuver your way around such impediments to prosperity, you might be interested in a new report that examines licensing requirements for each state plus the District of Columbia and ranks them from best to worst.

You are reading The Rattler from J.D. Tuccille and Reason. Get more of J.D.'s commentary on government overreach and threats to everyday liberty.

One in Every Five Jobs Requires Government Permission

The burden of occupational licensing has changed little from last year's edition of this report. "Occupational licensing affects more than 20% of workers in the United States," note co-authors Noah Trudeau of the Archbridge Institute, which publishes the State Occupational Licensing Index, Edward Timmons, director of the Knee Regulatory Research Center at West Virginia University, and Clemson University's Sebastian Anastasi. That's the same share as in 2023, though this year's Index looks at 284 occupations rather than the 331 considered in 2023 because of consolidation of some job categories and reconsideration of what constitutes a license.

Broad licensing requirements are a big problem because "there is evidence that licensing requirements raise the price of goods and services, restrict employment opportunities, and make it more difficult for workers to take their skills across State lines," as an Obama administration report found in 2015.

And while advocates for licensing insist that they're defending the public, "the public safety and health rationale for regulating many of those occupations ranges from dubious to ridiculous," argued Maureen K. Ohlhausen, the Trump administration's acting Federal Trade Commission chairman, in 2017. "Consumers can, and do, easily evaluate the quality of interior designers, make-up artists, hair-braiders, and others."

Research finds "no evidence that licensing raises quality and some evidence that it can reduce it," added a 2022 Institute for Justice report.

So, if Democratic and Republican presidential administrations agree that occupational licensing does harm, and independent researchers concur, why are the rules still in place? Because they are imposed by state governments which determine their own policies. That means there's wide variation from state to state, and promising reforms in some that have yet to be adopted by others.

State-Inflicted Barriers to Work

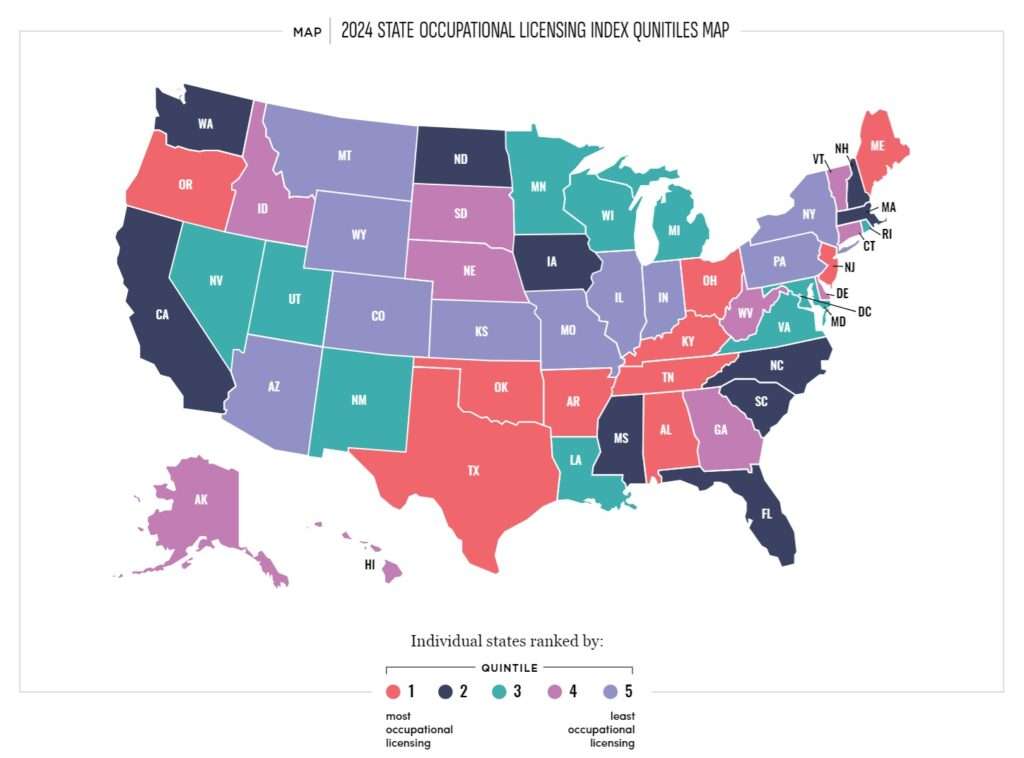

"The five worst states for occupational licensing are Texas, Arkansas, Tennessee, Oregon, and Alabama (in that order), based on the total number of barriers to entry into the labor market and the overall number of licenses required," the Archbridge Institute highlighted in a statement announcing the report. "The five best states, on the other hand, are as follows: Kansas, Missouri, Wyoming, Indiana, and New York (also in that order). Some of the most licensed professions are attorneys, barbers, chiropractors, dentists, and real estate brokers, while some of the least licensed ones are denturists, interior designers, and ocularists."

The arbitrariness of licensing can be seen in the many jobs people can be arrested for working without a license in only a small number of states, while other states require no permission at all with no ill results. These occupations include interior designer (licensed in three states), lactation consultant (two states), and professional geophysicist (one state). As the FTC's Ohlhausen quipped in 2017, "I challenge anyone to explain why the state has a legitimate interest in protecting the public from rogue interior designers carpet-bombing living rooms with ugly throw pillows."

The rankings suggest that occupational licensing doesn't follow common assumptions that red states are market-friendly and blue states are not. That may apply when it comes to taxes and other regulations, but licensing restrictions and reforms seem to cross partisan boundaries. In 2024, Republican-led and Democratic-led states mingle together from the top to the bottom of the index—something most easily seen when the states are divided by quintile. There may be other factors at play in the susceptibility of licensing boards to being captured by the occupations they oversee and turned to limiting competition.

For comparison, Texas, with the highest licensing burden in the U.S., has 199 barriers to work (meaning that tasks associated with an occupation require a license even if the occupation itself isn't licensed) and requires licenses for 163 jobs. Kansas, with the fewest restrictions, has 136 barriers to work and requires licenses for 117 jobs.

Signs of Improvement

Among the positive changes of recent years, point out the Archbridge authors, is the adoption of universal licensing recognition by 26 states. While not as helpful as fully dumping licensing requirements, according to the Index this reform "provides a pathway for licensed or credentialed workers to transfer licenses for nearly all occupations from state to state without typical frictions (e.g., the need to complete more training or long wait times)."

Arizona was the first state to recognize licenses from elsewhere, starting in 2019. The Copper State is in a solid 41st place (first place is the most restrictive and 51st the least). It has 162 barriers to work and requires licenses for 125 occupations. But Arizona's universal recognition isn't perfect; the Index gives the state a silver medal for its implementation, which recognizes the out-of-state licenses of people who move to the state and become residents. Bronze medals go to those that recognize licenses from elsewhere that have requirements "substantially similar" to state-issued licenses—an arbitrary measure that blocks many experienced people from easily working in another state. Gold medals go to states that have neither residency nor "substantially similar" requirements.

With the State Occupational Licensing Index in its second year, the Archbridge Institute and the Knee Center, whose database is used in this report, aren't the first organizations to study licensing requirements and the damage they do. Trudeau, Timmons, and Anastasi point out the similar rankings offered by the Institute for Justice's License to Work and the National Council of State Legislatures' National Occupational Licensing Database.

"License to Work 1, 2, and 3 focus on a list of 102 low- to medium-income occupations," note the Index authors. "NCSL, on the other hand, focuses on 48 occupations across states with the specific requirement that the occupations be licensed in 30 or more states, not require more than a four-year degree, and have positive projected growth over the next decade."

The Cato Institute's Freedom in the 50 States also includes a measure of occupational freedom in its rankings. The organizations share similar concerns, but they look at different (though overlapping) occupations and use varying methodologies. They all do an important service in scrutinizing legal barriers to employment and competition.

"Only through awareness and education can we hope to encourage more research on occupational licensing and pursue reforms that alleviate the burden on America's workers, especially universal licensing recognition," comments co-author Edward Timmons. "In an uncertain labor market, we must recognize and remove the licensing-related barriers to work, financial security, and human flourishing."

Research like this report does important work in documenting the harm caused by regulatory requirements imposed by government officials in the false name of public safety, but which are ultimately responsible for enormous damage to prosperity and opportunity.

Show Comments (38)