Did Decriminalization Boost Drug Deaths in Oregon?

Recent research finds "no evidence" that it did, undermining a key claim by critics of that policy.

Oregon is considering legislation that would recriminalize low-level drug possession, reversing a landmark reform that voters approved in 2020. Although critics of that ballot initiative, Measure 110, cite escalating drug-related deaths, decriminalization is not responsible for that trend.

Opioid overdose fatalities have been rising nationwide for more than two decades. That trend was accelerated by the emergence of illicit fentanyl as a heroin booster and substitute, a development that hit Western states after it was apparent in other parts of the country.

"Overdose mortality rates started climbing in [the] Northeast, South, and Midwest in 2014 as the percent of deaths related to fentanyl increased," RTI International epidemiologist Alex H. Kral and his colleagues noted at a conference in Salem, Oregon, last month. "Overdose mortality rates in Western states did not start rising until 2020, during COVID and a year after the introduction of fentanyl."

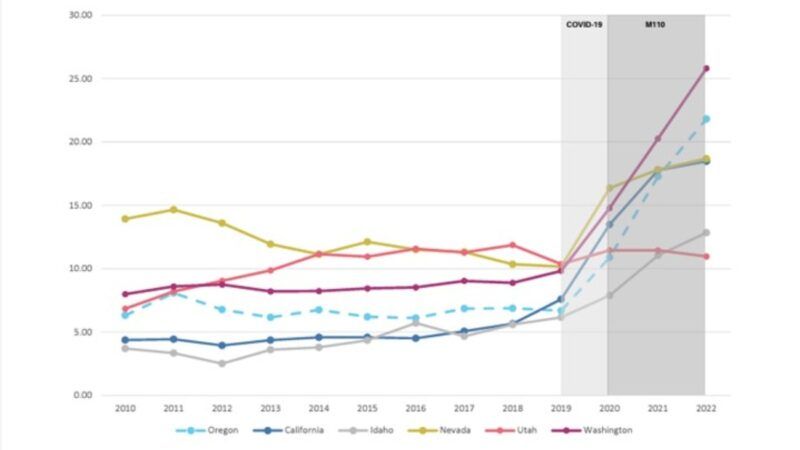

That lag explains why Oregon has seen a sharper rise in opioid-related deaths than most of the country since 2020. But so have California, Nevada, and Washington, neighboring states where drug possession remains a crime.

Decriminalization under Measure 110 took effect in February 2021, and a 2023 Journal of Health Economics study estimated that it was associated with a 23 percent increase in "unintentional drug overdose deaths" that year. But "after adjusting for the rapid escalation of fentanyl," Brown University public health researcher Brandon del Pozo reported at the Salem conference, "analysis found no association between [Measure 110] and fatal drug overdose rates."

Kral and his collaborators concurred, saying "there is no evidence that increases in overdose mortality in Oregon are due to" decriminalization. That is consistent with the results of a 2023 JAMA Psychiatry study, which found "no evidence" that Measure 110 was "associated with changes in fatal drug overdose rates" during the first year.

The expectation that decriminalization would boost overdose deaths hinges on the assumption that it encourages drug use. Yet an RTI International study of 468 drug users in eight Oregon counties found that just 1.5 percent of them had begun using drugs since Measure 110 took effect.

Because Measure 110 did nothing to address the iffy quality and unpredictable potency of illegal drugs, it is not surprising that overdoses continued to rise, consistent with trends in other Western states. Those problems are created by drug prohibition and exacerbated by efforts to enforce it.

When drug consumers do not know what they are getting, as is typical in a black market, the risk of a fatal mistake is much greater. That hazard was magnified by the crackdown on pain pills, which pushed nonmedical users toward more dangerous substitutes, replacing legally produced, reliably dosed pharmaceuticals with products of uncertain provenance and composition.

Worse, the crackdown coincided with the rise of illicit fentanyl, which is much more potent than heroin and therefore made dosing even trickier. That development also was driven by prohibition, which favors highly potent drugs that are easier to conceal and smuggle.

The perverse consequences of these policies soon became apparent. The opioid-related death rate, which doubled between 2001 and 2010, nearly tripled between 2011 and 2020, even as opioid prescriptions fell by 44 percent. In 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention counted more than 80,000 opioid-related deaths, nearly four times the number in 2010.

Although it is hard to make much progress in reversing these depressing trends without addressing the underlying legal regime, harm reduction tools such as fentanyl test strips, naloxone, and supervised consumption facilities can make a dent in the death toll by preventing or reversing overdoses. Treating drug users as criminals, by contrast, compounds the harm caused by prohibition, unjustly punishing people for conduct that violates no one's rights.

"It is no longer 2020," Albany, Oregon, Mayor Alex Johnson told state legislators last week, urging recriminalization. "The world has changed. Fentanyl has become a death grip." Before legislators take Johnson's advice, they should reflect on how that happened.

© Copyright 2024 by Creators Syndicate Inc.

Show Comments (70)