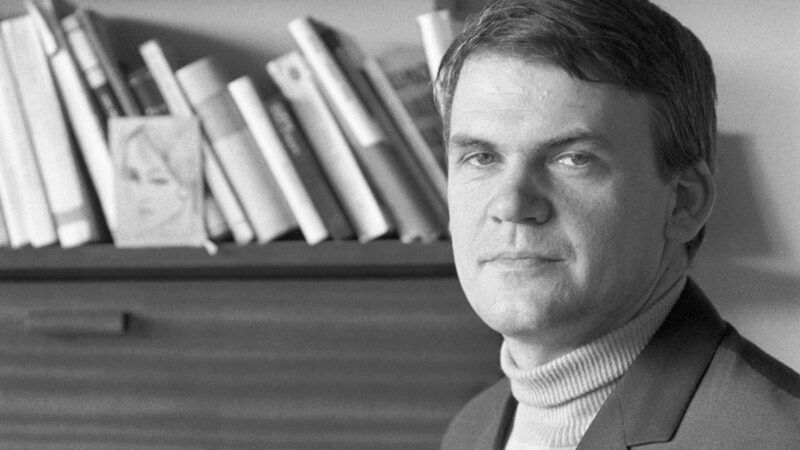

Milan Kundera's Eternal Feud With Václav Havel

In clashing bitterly over how an individual should best confront government evil, the two most famous Czech anti-communists unwittingly demonstrated how totalitarianism mangles human lives.

There is a memorable 15-page section of The Unbearable Lightness of Being, the most famous work by the celebrated Czech-French novelist Milan Kundera, who died this week at age 94, in which the world-weary and sexually voracious brain-surgeon protagonist Tomas dithers over whether he should sign a petition asking Czechoslovakia's communist president to grant amnesty to all the country's political prisoners. The setting is the early 1970s, and the government is midway through the societal suffocation process grotesquely marketed as "normalization."

Signing the petition would be "possibly noble but certainly, and totally, useless (because it would not help the political prisoners)," Tomas muses, as his long-estranged biological son and a dissident editor await an answer, "and unpleasant to himself (because it took place under conditions the two of them had imposed on him)." It was irritating to be put on the spot.

In the end, citing a late-breaking concern for his wife, the doctor declines. "Tomas could not save political prisoners, but he could make Tereza happy. He could not really succeed in doing even that. But if he signed the petition, he could be fairly certain that she would have more frequent visits from undercover agents, and that her hands would tremble more and more."

What the novel's hundreds of thousands of American admirers could not have possibly known was that Tomas' conflicted refusal mirrored a hauntingly similar choice Kundera himself had made at basically the same geopolitical place and time. Dissident playwright Václav Havel in the dreary normalization year of 1972 circulated a petition asking Communist Party General Secretary Gustáv Husák to free all political prisoners during the traditional Christmas amnesty. Thirty-four brave intellectuals signed, Kundera conspicuously did not.

That decision, and the underlying dilemma of how an individual should best oppose a totalitarian state, formed the basis of one of the most consequential, long-lasting, and ultimately tragic political/literary feuds of the past six decades.

Kundera and Havel, the Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig of Czech letters, did more than any other two people to popularize the plight of Czechs and Slovaks subjugated by Soviet communism after the August 1968 Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia. The two had been among the leading figures of the "Prague Spring" cultural and political liberalization during the five years before the tanks. But the mentor and his pupil (Kundera, seven years senior, had been a key sponsor of Havel's intellectual ambitions as early as the late 1950s) clashed vituperatively for a quarter-century over the optimal tactics for confronting commies, an experience that cemented the late novelist's alienation not just from his home country, but eventually from his own mother tongue.

It's not hard to depict the divide between the two men in ways more flattering to the playwright/president. Kundera was the Stalinist-poet-turned-reform-socialist; Havel was a lifelong anti-communist. Kundera was the émigré who found fame describing the Czech condition from afar after decamping to Paris in 1975; Havel was the guy who decided to stay and fight, finding both fame and lengthy jail time after describing the Czech condition in minute and revelatory detail that same year in a remarkable open letter to Husák.

Most significantly, the two disagreed over the meaning and import of individual Davids aiming their slingshots at the all-encompassing Goliath. Kundera dismissed such quixotic gestures as "pure moral exhibitionism"; Havel countered that loudly "living in truth" could unleash the "power of the powerless." The collapse of communism in 1989 seemed to prove Havel right.

But history (which Kundera mordantly maligned as "stupid") almost never produces fairy tales as wholesome as the Velvet Revolution, and the eternal debate over activist motivation and strategy knows no geographical or temporal bounds. The Kundera/Havel fault line is easily mappable onto our present day—should political activity be geared toward plausible change or long-shot miracles? When does realism become pessimism and even fatalism? And is there any real future for the small nation-states between Germany and Russia?

***

Kundera's refusal to sign the petition was an event significant enough that it appeared in fiction six years prior to The Unbearable Lightness of Being, in Havel's withering 1978 play Protest. In it, Havel's dramatic alter-ego Vanek, a dissident writer fresh out of prison, is invited to the home of his squishier pal Stanek, a TV writer who has built a good living out of coloring safely between the regime-approved lines. The play's whole dramatic tension, and laborious intellectual sparring, rests on whether Stanek will sign Vanek's petition to free a singer from jail.

"What follows is a lengthy monologue by Stanek that is painful to read, so naked are his feelings of shame, and so blatant are his attempts to suppress that shame with ostensibly objective, tactical considerations," wrote Benjamin Herman at Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, in an examination of the testy Kundera/Havel relationship a few weeks after the latter's 2011 death. "In the end, Stanek rationalizes himself into the perverse position that adding his name to the petition would actually be selfish, because it would glorify himself but do nothing for the singer. Sound familiar?"

The familiarity was not merely with Kundera's (in)action in 1972, or Tomas' rationalization in 1984, but with a scorching public polemic between the two men after the Soviet invasion, in those waning months before independent expression in Czechoslovakia was snuffed out by the state. This famous Kundera-Havel-Kundera exchange, the last time either would be published in their home country for 20 years, started off as a seemingly innocuous attempt by the elder statesman to salve the fresh wounds of occupation.

"I refuse to call it a national catastrophe, as our somewhat tearful public tends to do today," Kundera wrote in a December 1968 essay titled "Czech Destiny." To the contrary, those who had pushed for "socialism with a human face," who had insisted on a uniquely Western-facing and independent culture despite the ever-present threat of shackles imposed from the East, should feel pride at having "placed Czechs and Slovaks in the center of world history." It is the Czech lot to be hemmed in by imperial neighbors; in that context, independent survival is heroic.

"Havel's reply a month later," his biographer and friend (and former Czech ambassador to the United States) Michael Žantovský wrote, "stunned many people by the openly adversarial, almost hostile tone with which he attacked Kundera's argument." The venom indeed leaps off the page:

All of us—the entire Czech nation, that is—must no doubt be pleased when we find out that we have gained recognition for our stand in August, even from Milan Kundera, that blithely skeptical, intellectual man of the world who always was apt to see our rather negative angles.

Havel dinged his erstwhile friend (quite accurately, it would turn out) for Pollyannaishly declaring "enormous hope" for Prague Spring–style liberalism enduring, and attacked the "Czech Destiny" framing as "pseudo-critical illusionism" that rationalizes defeat as the best one can hope for.

"I do not believe in this fate, and I think that first and foremost we ourselves are the masters of our fate," Havel wrote. "We will not be freed from this by…hiding behind our geographic position, nor by reference to our centuries-old lot of balancing between sovereignty and subjugation. Again, this is nothing but an abstraction cloaking our concrete responsibility for our concrete actions."

The gloves were off. Kundera responded with a March 1969 essay titled "Radicalism and Exhibitionism" attacking Havel's grimmer assessment of the post-invasion situation as a kind of intellectual brush clearing for vainglorious acts of futility:

The person eager for self-display gravitates towards an understanding of the situation as hopeless, for only a hopeless situation can free him from the duty of tactical consideration and fully clears some space for his self-expression, for his exhibition. And he not only understands it as a no-win situation, but he (attracted by the irresistible seduction of theatrical conflict) is even, with his behavior, his "risky acts," capable of making it so. Unlike reasonable (which in his lexicon means cowardly) people, he does not fear defeat. Nevertheless, he is not so wretched as to long for victory. To be more exact, he does not long for the victory of the just thing he is working for; he himself is most victorious precisely in the defeat of the thing he champions, because it is the defeat of the just thing that illuminates, with the light of an explosion, all the misery of the world and all the glory of his character.

With this backdrop, Kundera's refusal to sign Havel's petition in 1972 looks almost pre-ordained; the ask itself like a theatrical act of fraternal cleavage. No wonder the two gifted writers just couldn't let it go.

What happened next is the kind of paradox Central European intellectuals love: The two men switched sides. That is to say, having fled the country in 1975, and finding a new international audience for his novels and essays, Kundera became one of the most pitiless assessors of the attempted "strangulation" of Czech culture, declaring his departed nation on several occasions at being on the verge of death. Havel, having plunged headlong into open opposition in 1975, now bristled at such pessimism, celebrating the green shoots of culture he and his fellow dissidents were helping seed, even in the face of persecution.

"I am irritated by his repeated pronouncements about the cultural graveyard here; whatever we are we do not think of ourselves as corpses," Havel complained in a 1984 letter.

Their respective reputations now grew, exponentially. Havel's Charter 77—an open petition to a totalitarian government!—not only galvanized Czechoslovakia's dissidents and civil society, it became the single most influential anti-communist movement under Soviet misrule, with reverberations felt to this day in places like Cuba and China. The Unbearable Lightness of Being, meanwhile, became an international sensation, introducing a new generation to the horrors of the 1968 invasion. Kundera's essays, too—particularly "The Czech Wager" and "The Tragedy of Central Europe" in The New York Review of Books—had a profound impact on the way people thought about the captive nations between Berlin and Moscow.

And still they were not done talking about 1972. In his 1986 book-length interview Disturbing the Peace, Havel, while otherwise downplaying the supposed rift with Kundera, nonetheless pointed to the lasting importance of that initial petition as "the first significant act of solidarity in the Husák era":

All those who did not sign or who withdrew their signatures in ways similar to Tomas in Kundera's novel. They said they couldn't help anyone this way, that it would only annoy the government, that those who had already been banned were being exhibitionistic, and, worse, that through this petition, they were trying to drag those who still had their heads above water down into their own abyss by misusing their charity. Naturally, the president did not grant an amnesty, and so some signatories went on languishing in prison, while the beauty of our characters was thus presumably illuminated. It would seem, therefore, that history proved our critics to be correct.

But was that really the case? I would say not. When the prisoners began to come back after their years in prison, they all said that the petition had given them a great deal of satisfaction. Because of it, they felt that their stay in prison had a meaning: It helped renew the broken solidarity.…

But the petition had a far deeper significance as well: It marked the beginning of a process in which people's civic backbones began to strengthen again. This was a forerunner of Charter 77 and of everything the Charter now does, and the process has had undeniable results.

Three years later, that process led to results almost no one had foreseen.

Czechoslovakia's liberation from captivity and transition to liberal democracy should have been the end of the Kundera-Havel feud. Certainly, Havel tried magnanimously to bury the hatchet and reunite the Czech author with his home audience; dining with the novelist in Paris ("I don't have the impression he's trying to live in isolation from his native country—only from the media," he said hopefully), and laboriously negotiating a public rapprochement at a 1993 production of a Kundera play in Brno.

But Kundera, who had only traveled back home a couple of times in disguise, backed out at the last minute. The man whose main literary themes (besides sex) were betrayal and exile, just could not steer out of the long curve that communists had imposed on his life trajectory. He dragged his feet on having his novels published in the Czech Republic, blocked attempts at republishing or translating his nonfiction, refused all media interviews, turned down all film adaptations after his disappointment with Unbearable, micromanaged translations, and seemed to live life as more of a paranoid recluse than a cosmopolitan bon vivant. Most tragically of all, for a man who did so much to propagate the notion of a unique Czech literary and national identity, he began in 1993 to write all his novels in French.

In a 2019 interview with the Czech News Agency, Kundera's wife and literary agent Vera Kunderova made the absurd allegation that dissidents back home had always criticized the world's most popular Czech author because they feared his potential political power. "They chose as a leader of the anti-Communist opposition Havel, fearing that Milan, who was much more known abroad, could want to head the political opposition himself," Kunderova said.

The charge may have been nonsensical, but the paranoia was not. As many of the estimated 200,000 post-1968 émigrés had to find out the hard way, the people they left behind could be extremely small-minded and cruel toward the people who found a better life in the West. There was much to criticize in Kundera's analyses and choices at various times, but the level of rancor from his homeland over the years suggested a certain jealousy, or at least a lack of proportionality toward a person who had done so much to champion their cause. It wasn't Milan Kundera who sent in the tanks and jailed the opposition and stifled society; it was the Soviet-dominated communists who forced a never-ending series of terrible choices onto everybody in their path.

The coda to Kundera's Czech-facing career was thus appropriately sour: In 2008, he was accused, I think credibly if unverifiably, of having informed on a returned defector to the secret police in the dark old days of 1950, when he was still an enthusiastic young communist. The defector would go on to serve 14 years in a labor camp. Kundera fiercely denied the charges, calling it a "smear campaign." One of the many literary lions who leaped to the old former commie's defense? Havel.

People who live under totalitarian rule deserve our grace. People who fight against it, even imperfectly, with skeletons in their closet, deserve our thanks. May the rest of us never have to face such terrible choices.

Show Comments (26)