Photos Show the Transformation of Great Britain

A new exhibit at the National Gallery of Art displays how the U.K. changed in the 1970s and '80s.

Not so long ago, Great Britain was deemed "the sick man of Europe." The 1970s were plagued by inflation, labor union strikes, and a rise in government spending as a percent of GDP. Now, a new photography exhibition at the National Gallery of Art (NGA) invites an American audience to consider snapshots of life as it was for everyday Britons from the 1970s to the 1980s and how the nation transformed from an ailing, deindustrializing country to greater economic prosperity starting in the 1980s. It's a hard story to tell, because to this day people have feelings about the upheaval that came with that change.

The exhibition, "This Is Britain: Photographs from the 1970s and 1980s," features 45 images taken by a diverse set of around 19 documentary photographers who wanted to convey the circumstances and/or hardships of a particular community. The late photographer Chris Killip (1946–2020), for example, lived in a caravan (trailer park) in northeast England for more than a year, photographing a community of people who subsisted off unemployment benefits and selling waste coal that washed up on the beach (see: Margaret, Rosie, and Val, Seacoal Camp, Lynemouth, Northumberland).

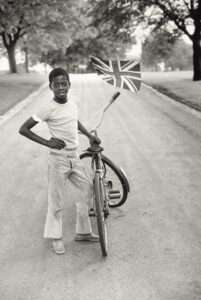

Photographer Vanley Burke, raised in Jamaica until he moved to Birmingham as a teenager in 1965, chronicled black British life, such as a smiling boy posing in 1970 with his bicycle, flying the British flag in a way that conveys the significance of immigrants' self-identification as British (see: Boy with Flag). Graham Smith photographed his economically depressed community in northeast England. His 1981 poignant image Clay Lane Furnaces, South Bank, Middlesbrough seems to tell a story of a receding industry.

An American curator, Kara Felt, spurred this NGA exhibition. Her photo selections and accompanying text make this, in a real sense, a British story told by an American to an American audience. Felt was initially inspired by a similar 2015 exhibition at the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool. The 1970s and '80s represented a "real renaissance in British photography," Felt said in an interview. It was an era in which museums began supporting photography, and schools for the profession grew less vocational and more focused on the medium's artistic aspects, she explained. She also discovered it had been 30-some years since the last major presentation of such photographs to an American audience, a 1991 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York called "British Photography from the Thatcher Years."

The first thing to know about 1970s Britain when viewing the photographs is that things got really bad. Inflation teetered over 24 percent in 1975. The same pound bought far less than before. That is stressful to contemplate, given the U.S. experience in the 1970s era—and again recently—struggling with too-high inflation that peaked at nearly 15 percent by April 1980. Meanwhile, the British government actually owned and operated whole industries (steel, railways, airways, airports, and aerospace) along with utilities (gas, electricity, telecoms, and water). That wasn't going well. Too many industries were propped up by taxpayers rather than striving to win consumers and compete globally.

To make matters worse, labor unions staged relentless strikes throughout the 1970s to pressure lawmakers into raising their wages. "Because so many industries were nationalized, wage rises were agreed over 'beer and sandwiches' in 10 Downing Street, not in corporate offices; and if the politicians claimed to be out of money, the unions could hold the public to ransom through strike action," explains my colleague, Iain Murray, who hails from South Shields, the "industrial heart of the northeast of England," where most of the menfolk were employed in shipbuilding and coal mining.

In fact, the list of striking industries is somewhat horrific—crucial sectors of the economy like gravediggers, car makers, coal miners, train drivers, garbage collectors, nurses, sewage treatment workers. The strikes disrupted everyday life, especially during the "Winter of Discontent" between November 1978 and February 1979. This meant problems like hours or days with no electricity, the dead going unburied, piles of uncollected refuse, and even raw sewage poured into the rivers Thames and Avon.

These dire circumstances led to voters ending Labour Party rule and instead, in May 1979, giving the Conservative Party a chance to run the country. And this brings us to the political figure inexorably associated with the decade to follow: Margaret Thatcher, the "Iron Lady" elected Conservative Party leader in 1975 and then Prime Minister from 1979 to 1990. She was and is alternately despised and revered, depending on who you ask.

"Margaret Thatcher was not a conservative; she was a revolutionary," explains Marian Tupy, a scholar at the libertarian Cato Institute. "The structure of the British economy changed under Thatcher," further transitioning from heavy manufacturing to a service economy. In 1970, 30 percent of the U.K. economy was manufacturing and about 56 percent services, according to the U.K. Office for National Statistics. By 1989, it was 20 percent manufacturing and nearly 67 percent services. "Instead of being a sixth or 10th generation miner, people had to try something new," said Tupy.

In short, Thatcher was not trying to conserve a long-standing status quo. She espoused free market values, broke the power of the labor unions, junked price controls and other stifling economic regulations, and set about privatizing government-run industries. "We have stopped creating wealth," Thatcher told William F. Buckley in 1977. "To create more, you need a slightly freer society and you need an incentive society." That kind of change didn't sit well with everyone. It meant hard times.

"Looking back to the 60s and 70s, you were thinking you had a job for life, you know?" a former coal miner turned museum curator told a Welsh newspaper in 2020. "The collieries [coal mines] had always been there in one form or another. The education was quite good if you wanted it in the colliery, and the wages were reasonable. So, you thought, 'that's it.' And then all of a sudden, the place shut."

When Thatcher took office in 1979, 25 percent of unemployed people had been out of work for over a year. By 1984, it was 39.6 percent. At the end of 1973, the unemployment rate itself was a record low of 3.4 percent but had almost tripled to 11.9 percent by April of 1984. There was a real initial human cost to the Thatcher reforms. But by the mid to late 1980s, the country was enjoying an economic boom.

Over at the NGA exhibition, the 1980s room is introduced by the caption "Picturing Absurdity in the Thatcher Years" and explains that photographers "used the brash colors of advertising to poke fun at the rise of leisure activities, consumerism, and corporate greed" of that boom period and "openly satirize long-held traditions and question emerging values in British society." This includes, for example, an image from the 1989 Cambridge University Ball by Chris Steele-Perkins, in which party revelers are put under hypnosis, just for fun. The accompanying curator text explains this image "wryly comments on the excesses and zombie-like conformity of upper-class British youth." (Making fun of the "yuppies," as Tupy aptly put it.)

As a viewer, I could readily rewrite this as "capturing delight and relief that people now had more leisure time and activities, access to better and more affordable consumer goods, and all thanks to private sector companies generating real economic prosperity." That's not how the photographic journalists seem to see it. Behold, for example, photographer Paul Reas's 1987 garish image of a man shopping for pork while wearing a pig-motif jumper, Hand of Pork, Newport South Wales. Or the set of photos by Anna Fox "mock[ing] the escalating materialism associated with Margaret Thatcher" and "prob[ing] the competition, stress, and alienation of London office work."

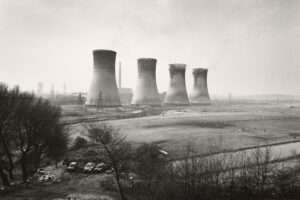

Photojournalists may have been, on average, more cynical about consumerism than ordinary people. The trappings of industry and manufacturing can appear noble and beautiful, in a way (see: Agecroft Power Station, Salford by John Davies). But industrial-age manual labor was no joke.

In November 2021, I visited the remnants of a turn-of-the-century coffin-making factory in Birmingham, a leading city in the Industrial Revolution, the second largest city in Britain, and the hometown of Rock and Roll Hall of Fame band members of Duran Duran. The Newman Brothers factory is now the Coffin Works museum. But back in the day, workers manufactured coffins for the booming business of formal funerals. Sometimes, if they weren't careful or fast enough, they could lose a finger in the machinery, like the "drop stamp" used to press a shape into a piece of sheet metal. All day, a worker had to repeatedly drop a heavy weight or hammer onto the metal piece and then whisk it away, swiftly replacing it with a new metal piece. Windows, which many 21st-century workers in developed countries now take for granted, were needed for daylight to illuminate the factory but were made opaque to prevent workers from window gazing. There's a reason so many young people probably didn't want the jobs their parents and grandparents had.

The country's transformation to a post-industrial economy had tradeoffs, but they surely amounted to a net gain for Britons. Where photographers may seem alternately nostalgic and cynical, an American viewer of the National Gallery of Art exhibition could see a country's emergence from drudgery to opportunity, abundance, and prosperity.

It's worth mentioning that the exhibition also references violent political unrest of the era, in England and over Northern Ireland, along with two films dealing with race and sexuality, all fraught topics worthy of their own consideration and review.

"This Is Britain: Photographs from the 1970s and 1980s" is on view at the National Gallery of Art from January 29 through June 11, 2023, in the West Building.

Show Comments (76)