The Supreme Court Weighs State Sovereignty and the Status of Puerto Rico

The justices heard oral arguments in Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico v. Centro de Periodismo Investigativo.

One of the ways in which the U.S. Supreme Court recognizes the interests of the states is through a doctrine known as state sovereign immunity. This doctrine says that a state generally may not be sued in federal court unless it consents to it. A state is, of course, free to waive its sovereign immunity. And Congress may sometimes waive a state's sovereign immunity, too, whether the state likes it or not. However, the Supreme Court held in Atascadero State Hospital v. Scanlon (1985), "Congress may abrogate the States' constitutionally secured immunity from suit in federal court only by making its intention unmistakably clear in the language of the statute."

The Supreme Court heard oral arguments this week in a case that applies those sovereign immunity principles to the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico. Centro de Periodismo Investigativo is a Puerto Rican nonprofit news organization that seeks to obtain public documents, via a Freedom of Information Act-like request, from the Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico, an agency established by the U.S. Congress to implement the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act of 2016 (PROMESA). Among other things, PROMESA says that "any action against the Oversight Board, and any action arising out of [this law], in whole or in part, shall be brought in a United States district court for the covered territory or, for any covered territory that does not have a district court, in the United States District Court for the District of Hawaii."

That statutory language, the oversight board argues in Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico v. Centro de Periodismo Investigativo, fails the "unmistakably clear" test for abrogating the sovereign immunity of the board, which gets its sovereign immunity as an arm of the Puerto Rican government, which itself gets sovereign immunity as a state-like entity under the authority of the United States. "There is zero evidence in the text or legislative history of PROMESA that Congress ever considered abrogating or intended to abrogate the Board's immunity," the oversight board told the Court in its principal brief.

The news outfit Centro counters by arguing that because Puerto Rico is not entitled to sovereign immunity in the first place, the Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico is not entitled to it either. "State sovereign immunity belongs to States. And Territories are not States," Centro told the Court in its brief. "When subjecting territories to suit in federal court, Congress need not satisfy a clear-statement rule that requires Congress to express its intent to abrogate state sovereign immunity. There is thus no bar to federal courts entertaining [Centro's] suit against the Board requesting documents about how the Board runs Puerto Rico."

Justice Sonia Sotomayor did not sound thrilled with the scope of Centro's argument. "You've not given me a reason why Puerto Rico should be treated differently than" the Indian tribes, which get sovereign immunity, she told Centro's lawyer. Sotomayor also likened Puerto Rico to "the territories that became states," such as Louisiana. "Historically, no territory was dragged into federal…or territorial courts unless their sovereignty had been waved." So, Sotomayor said, "to the extent that the United States has not permitted, entertained, or looked at suits against these territories, they've acted akin to states."

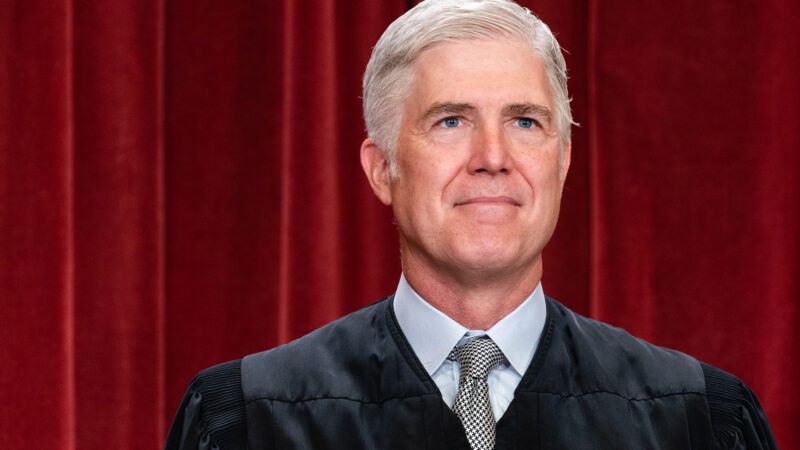

Justice Neil Gorsuch, meanwhile, suggested that the Court might want to find a way to avoid the question of territorial sovereign immunity altogether. "We don't have Puerto Rico before us. We have this Board that may expire and was a creation of Congress. We don't have the other territories," Gorsuch observed. "And it's a rather large and important constitutional question that really may only be relevant in a small number of cases too, given that, by statute, Congress has effectively given Puerto Rico sovereign immunity for purposes…of general purpose federal statutes." So why, Gorsuch asked Centro's lawyer, "aren't all those just good reasons to defer this question for another day?"

There are undoubtedly some tricky legal and political factors at play in this case. Fans of an expansive sovereignty doctrine, for example, might be quite happy to see the board prevail. So, too, might advocates of Puerto Rican statehood, since a Supreme Court judgment finding Puerto Rico "akin to states" would have obvious political value. Open records enthusiasts, meanwhile, would probably like to see Centro succeed in its journalistic quest.

And yet, as Gorsuch observed, no U.S. territorial government directly participated in a case that might well decide the big question of whether any of them are entitled to sovereign immunity as a constitutional first principle. That absence alone might be enough for a majority of the Court to follow Gorsuch's suggestion and find an off-ramp.

Show Comments (39)