Is There a Future for the City of Tomorrow?

The consequences of our obsession with urban dystopias and utopias

For all its pretense of futurism, EPCOT today feels like an anachronism. The first park to open after the death of Walt Disney, it dispenses with Disney World's traditional cartoon characters and Main Street, instead celebrating its founder's preoccupation with progress. Early promotional materials for the park—originally envisioned by Walt Disney as a full-scale Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow—invite visitors to imagine a world of technological progress, centralized planning, and scientific management.

Proposed in the twilight years of our collective love affair with urban utopianism, the park was opened in 1982. But for the next 40 years, when cities of tomorrow came up at all in culture, they were invariably dystopian, from the rampant crime of RoboCop's Detroit to the casual traffic violence of Akira's Neo-Tokyo. Until quite recently, urban settings were so central to dystopian fiction that entirely new cities were often invented to host them, as with Cyberpunk 2077's Night City, or Ghost in the Shell's New Port City.

In our initial attempts to build the city of tomorrow, we sliced up cities with freeways, remade neighborhoods along untested design principles, and locked communities into the zoning straitjacket. The results were an unambiguous failure, yet the nightmares they conjured led subsequent generations to double down on growth controls. The ironic result is that cities like Los Angeles today suffer from many of the crises predicted in cyberpunk futures, but in a form that is, for lack of a better word, boring. Say what you will about Blade Runner 2049's Los Angeles, at least it has holographic sex robots.

After a century of fantasizing about what it would be like to have technocrats set the terms of urban life—or fretting about what might happen if they don't—perhaps it's time for a city of tomorrow that lets individuals plan for themselves.

Yesterday's City of Tomorrow

For much of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Americans were infatuated with the idea of technological progress and prudent planning ushering in a golden age.

It isn't hard to see why: As innovations like steel framing and the elevator liberated building heights from the constraints of load-bearing walls, the rapid spread of streetcars and the automobile allowed cities to expand deeper into the countryside. An American once tethered to a low-slung hovel and a half-mile walking commute could now conceivably work out of a 30-story tower and commute each day from a distant suburbanizing periphery.

Books like Edward Bellamy's Looking Backward: 2000–1887 became runaway bestsellers. An unusually didactic piece of early science fiction, Looking Backward envisions a future America perfected by the nationalization of major industries and the micromanagement of the economy. Boston plays a starring role, replete with what would become standard fare for utopian cities, from climate control domes to instant delivery. Such innovations ultimately came to pass—but in the capitalist form of shopping malls and Amazon.

Inspired partly by Bellamy, Ebenezer Howard set out an equally fantastical urban vision in 1902's Garden Cities of To-morrow. In place of the dense, dynamic cities of his day, Howard envisioned self-sufficient "garden cities" of exactly 32,000 residents on 9,000 acres. Residences and commerce were to be strictly separated by successive rings of greenbelts, with up to six garden cities orbiting around a central city of 58,000 residents, all to be connected by railroads and canals.

As with Bellamy, Howard's work kicked off an international movement, with dozens of garden cities being built across the developed world. Here in the U.S., Greenbelt, Maryland; Greenhills, Ohio; and Greendale, Wisconsin, were built by the federal government as part of the New Deal–era Greenbelt Towns program. And as with Bellamy, details of Howard's vision would be realized by the private sector, with garden-city ideas informing the design of subdivisions.

The rise of mass automobile ownership likewise seeded new strains of popular urban utopianism. In an update on Baron Haussmann's remaking of Paris, the architect Le Corbusier variously excited and terrified French audiences with his 1925 proposal to replace much of historic Paris with rows of identical modernist high-rises towering over free-flowing traffic. At the 1939 New York World's Fair, General Motors' Futurama exhibit proposed something similar, inviting Americans to imagine a "future" 1960 city carved up by 14-lane freeways.

Arriving in the mid-1960s, Walt Disney's original vision for EPCOT drew liberally from these various disparate traditions. After all, Disney didn't intend his Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow to be just another theme park—it was supposed to be a trial run for the city of tomorrow.

"EPCOT will be a planned environment, demonstrating to the world what American communities can accomplish through proper control of planning and design," a narrator explains in an early promotional film. EPCOT was to take a potpourri of high modernist urban planning ideas to their logical extreme: Residences, shopping, and industry would be strictly separated and bounded by greenbelts. Daily life would happen within the confines of megastructures. Underground freeways and PeopleMovers would ensure the seamless flow of traffic. And large corporations on friendly terms with planners, such as General Electric and DuPont, would be the stars of the show.

The trouble for Disney was that, by the time EPCOT was first announced, many of the experiments in urban living it proposed were already well underway—and the result was proving to be a nightmare.

Planning the Dystopian City

The economist John Maynard Keynes once quipped that we "are usually the slaves of…some academic scribbler of a few years back." By the second half of the 20th century, this was certainly true of the American city.

Progressive dreams of technocratic planning yielded zoning codes that criminalized the mixed-use patterns that had defined cities since the dawn of human settlement. Fanciful notions of garden suburbs gave way to the practical reality of mass suburbanization, prescribed and subsidized by a new suite of federal housing policies. A frenzy of urban freeway construction helped to facilitate this exodus, carving up and segregating communities in the process.

The results proved catastrophic. To connect cities to newly booming suburbs, planners ripped apart neighborhoods to make way for freeways, displacing many thousands of residents and businesses while ensnaring downtowns like Kansas City's. Ill-conceived urban renewal wreaked even more havoc, with St. Louis' Pruitt-Igoe development—totaling 33 high-rise modernist towers—being built and demolished in only 18 years. Cities like Buffalo lost half of their population between 1950 and 2000, despite stable metropolitan populations.

In this context, the city of the future gradually transformed into an oddly alluring object of terror, with neon and skyscrapers masking the state-sanctioned cronyism, ethnic tension, and casual violence that increasingly defined cities. Consider cyberpunk, the essential science fiction genre of the 1980s, which was built almost entirely around fears of the future. The genre reconfigures elements of the urban utopian script, recasting technological progress and corporate governance as vices rather than virtues, while warning viewers of the risks of unmanaged urban growth and diversification.

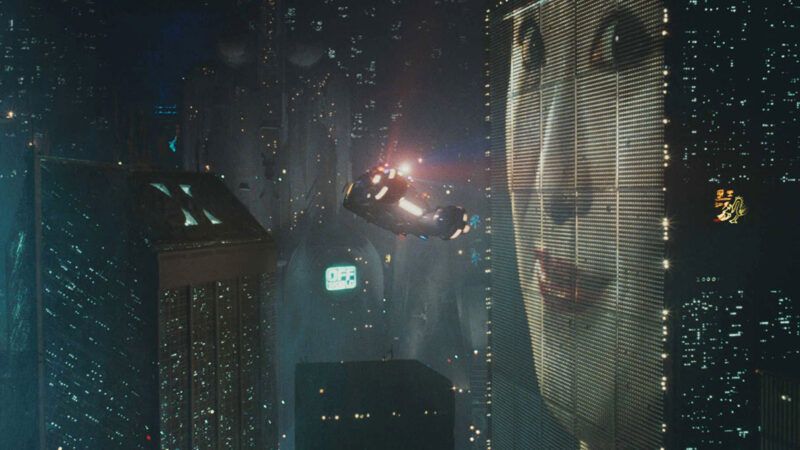

Blade Runner, released in 1982, depicts Los Angeles in the distant future of 2019 as a city overwhelmed by growth, environmental devastation, and corporate overlords. Navigating streets packed with refugees from dozens of nations, the viewer is meant to feel a kind of Lovecraft-in-Brooklyn horror. Corporate cover-ups and crooked cops undermine our hero's efforts to crack the case, while the presence of androids forces him to question his very humanity. An ever-present blimp reminds us of the only way out: "A new life awaits you in the off-world colonies."

Across various entries to the cyberpunk genre, urban growth is invariably framed as coming at the cost of the environment. Within cities, technological "progress" is depicted as sending every social problem into overdrive, from drug addiction to sexual depravity to social isolation. Where the EPCOT vision of tomorrow imagined captains of industry and state planners working together in harmony, entries like Cyberpunk 2077 reframe such collusion as an elite conspiracy, destroying the quality of life of everyday people to the benefit of crony capitalists.

Such nightmares were not without basis. Almost as soon as the first wave of modernist planners gutted cities, a second wave proposed increasingly desperate interventions for saving them, often at the cost of marginalized populations. In cities like Detroit, planners seized and demolished entire neighborhoods to make way for large corporate investors like General Motors. Similar urban renewal initiatives would be used to replace neighborhoods with stadiums, convention centers, and corporate headquarters in cities across the country.

At times, cyberpunk directly critiques such methods; at times, it merely frets over the devastating results. In RoboCop, released in 1987, a shadowy corporation attempts to tame Detroit's crime with an ethically dubious policing technology. In Escape From New York, an early cyberpunk film from 1981, Manhattan—at the time in the throes of a wave of violence—has become an islandwide prison.

Yet the pervasive cultural fear of cities that cyberpunk inspired didn't reverse the planning pathologies of a previous age. If anything, it turned them up to 11. Americans responded to dystopian depictions of the city of tomorrow not by reversing the centralized planning and pseudoscientific management that had so failed them, but by doubling down, with a fresh dose of technophobia added in for good measure.

At least through the early 2010s, zoning rules continued to tighten and urban freeways continued to widen. Today, you can barely ride an electric scooter across most cities, let alone a flying car. Many American cities ended up with cyberpunk problems—homelessness, inequality, sprawl—but without any of the compelling cyberpunk aesthetics. The desert of the real is the dumpy $2 million bungalow and half-empty strip mall that are illegal to redevelop because we are now too petrified of the city of tomorrow to allow any change.

Decentralizing Tomorrow

The best thing that could happen to the "city of tomorrow" might just be for the concept to die altogether. Aggressively laudatory or scornful depictions of future cities risk confusing at least as much as they clarify. And while utopian cities have largely fallen out of fashion, urban dystopias continue to plague popular culture. Just look at the most recent season of Westworld, which continues to try to scare viewers with corporate megastructures and holographic billboards that would today be largely illegal to build in Los Angeles.

Or maybe we just need less moralizing about the cities that are to come. Consider the 2013 cult classic Her, which offers an unusually humanistic vision of the city of tomorrow. The film's protagonist, Theodore, is depicted in decidedly futuristic spaces: navigating elevated pedestrian platforms, lounging on a high-speed train to the beach, looking pensively out upon a substantially built up Los Angeles skyline. Yet in each scene, Theodore and his thoughts are meant to draw the viewer's focus, often visually distinguished from the crowd by a bright red shirt. Unlike in past renditions of the city of tomorrow, Her's Los Angeles is not a character but a stage for millions of people to work through their individual plans.

The film's delightfully nonjudgmental tone promises neither salvation nor damnation through technology. To the extent that new androids trigger an existential crisis in Theodore, it is because he falls in love with one. The built form of the film's setting reflects this liberal sensibility. Its depiction of a near-future Los Angeles would be broadly familiar to Angelenos today, though with more skyscrapers and no more evidence of a homelessness crisis, suggesting that a degree of emergent growth rarely tolerated in historical renditions of the city of tomorrow has taken place in the intervening years.

A similar balance is achieved in Lost in Translation's Tokyo—a city which, to a Western viewer, may as well be from the future. The film follows the intersecting paths of visiting Americans Bob and Charlotte, each working through mid- and quarter-life crises, respectively. The film inverts cyberpunk tropes, recasting the aesthetics of exuberant capitalism, such as Shibuya's canyons of glowing signs, as harbingers of life. Tokyo's charm is rooted in its unplanned nature, with the duo meandering through pachinko parlors and karaoke bars, relishing in the spontaneity so often denied by the typical cocktail of modernist planning policies.

More so than with Her's Los Angeles, Lost in Translation's Tokyo evinces the blend of order and messiness characteristic of a healthy city. The trains come on time, yes, but Charlotte observes a man looking at porn on one. Across Tokyo, a chaotic medley of shops and signs front along prudently managed streets. In the film's iconic final scene, the two embrace amid a bustling and uninterested crowd. As we approach the credits, shots of Bob sitting in the back of the cab are interspersed with cuts to the Tokyo skyline as seen from his window—the individual imbues the city with meaning, rather than the other way around.

While urban theorists have largely abandoned utopian thinking—there is no contemporary Ebenezer Howard or Le Corbusier—the work of urban planner Alain Bertaud might lay the theoretical groundwork for this more liberal vision. As suggested by the title of his seminal work, Order without Design, there are no grand designs or master planners in Bertaud's formula. Rather, to truly understand cities is to appreciate them as emergent, self-organizing orders, the outcome of many millions of individual decisions. The evolving, patchwork skyline of Her hints at a future Los Angeles that embraces this reality.

The role of the planner within this framework is not to impose a singular design vision, but to create space wherein each of us can incrementally contribute to that design. If that sounds lofty, Bertaud is specific on the implications: Planners should demarcate the public and private realms, stewarding the former—building and managing the infrastructure needed to accommodate growth—while ceding the latter to the market. We know the city of tomorrow needs sewers, but we know very little about the appropriate scale or mixture of uses in any given neighborhood. Lost in Translation's Tokyo hews fairly close to this approach.

Even in EPCOT, there are signs that things are starting to change. After disembarking from the monorail, many families shuffle onto Spaceship Earth, a ride housed in the park's iconic geodesic sphere. Replete with animatronics and tricks of lighting, it tells the story of humanity's ascent from cave paintings to personal computing, concluding with breathless promises of innovations yet to come—a tale of undeterred progress, told with a strikingly dated utopian tone.

And yet, near the end of the ride, a new feature has been added. On the back of each seat, a screen unexpectedly lights up: "Welcome to Your Future!" After answering a few questions about each rider's lifestyle preferences—where they might like to live, how they might like to travel, and what they might like to do—a personalized vision of the future is depicted. Juvenile to be sure, but refreshingly liberal in its centering of the choices and desires of each visitor.

As one exits through the gift shop, a sign reads: "Shaping the future, together." Perhaps there is hope for the city of tomorrow yet.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Is There a Future for the City of Tomorrow?."

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Let's not forget that admission to the city of tomorrow is $109 per day and meals will set you back another $40 so you better have a well-paying job or you can fuck right off you deadbeat loser.

Sounds like any other city.

Great article, Mike. I appreciate your work, I’m now creating over $35,300 dollars each month simply by doing a simple job online! I do know You currently making a lot of greenbacks online from $28,300 dollars, its simple online operating jobs.

.

.

Just open the link————————————>>> http://Www.RichApp1.Com

Fewer homeless people, more pedophiles... tradeoffs.

Any blue city is well stocked with both.

Home earnings allow all people to paint on-line and acquire weekly bills to financial institutions. Earn over $500 each day and get payouts each week instantly to account for financial institutions. (bwj-03) My remaining month of earnings was $30,390 and all I do is paint for as much as four hours an afternoon on my computer. Easy paintings and constant earnings are exquisite with this job.

More information→→→→→ https://WWW.DAILYPRO7.COM

It's all swings and roundabouts.

Google pay 200$ per hour my last pay check was $8500 working 1o hours a week online. My younger brother friend has been averaging 12000 for months now and he works about 22 hours a week. I cant believe how easy it was once I tried it outit.. ???? AND GOOD LUCK.:)

https://WWW.RICHAPP2.com

And even easier than you think. Who hasn't looked at some piece of construction — a closet, a bathroom, an office, a house, a neighborhood, a whole town or city — and thought, if only I/we/someone had had the foresight, we wouldn't've had this design problem today, and wouldn't face the choice of living with its inefficiency or spending a ton on rebuilding, with the attendant inconvenience of either? There's a YouTube series on "stroads" — those bad compromises between urban streets and through-route roads — which could have been prevented only by advance planning, as if someone had known what people there would've wanted in the far future. But of course nobody does know, for others or even ourselves, that far ahead.

Which means we should go with the second-best strategy: design buildings and streets so they can change.

That’s what we do, at least as far as buildings go.

I’m not a fan of science fiction. Utopias and dystopias that are the same fucking thing droning on endlessly. Visions of cities designed by GM – destructed by Robert Moses – 17 lanes of freeways let’s all drive on parkways and park on driveways.

This shit goes nowhere. The grid is a really simple design. Thousands of years old. Works for cities around the world. Until the velocity of vehicles exceeds the ability of human flesh and bones to withstand it. And then the grid ceases to be a place for humans.

Fix the fucking grid. The car broke it Stop being such a tool and avoiding that

I’m not a fan of science.

Fixed it for you.

But for the next 40 years, when cities of tomorrow came up at all in culture, they were invariably dystopian, from the rampant crime of RoboCop's Detroit to the casual traffic violence of Akira's Neo-Tokyo.

Well, you clearly weren't watching Star Trek: TNG or several other series that had more optimistic things to say about the future. Then again, one person's utopia is another's dystopia: Star Trek's Federation is a socialist system in which currency has been abolished and yet everyone works in harmony for the betterment of society.

The only one that ever got it right was Demolition Man and the proliferation of Taco Bell.

Well that's also a socialist trying to describe some capitalistic nightmare future so I don't really like it, even as a joke. They clearly don't understand how the market works.

Try watching the movie then.

Taco Bell didn't proliferate, it conquered. Probably with graft and corruption.

I think it was with guns

You should watch Deep Space Nine. It was a really good take on the Federation, where they dealt with cultures outside the federation.

I have watched it. It's arguably better than TNG, but I was trying to make the point that there's more optimistic sci-fi out there, and DS9 views the Federation a bit less idealistically. It views people on Earth as blissfully out of touch, insulated from the consequences of their decisions and policies. It also occasionally pokes some fun at the failure of their capacity to understand commerce, in which the Federation still needs things from other cultures and then is frustrated that they can't facilitate getting those items because they've abolished trade.

Plus, the characters are fantastic.

Then again, one person’s utopia is another’s dystopia: Star Trek’s Federation is a socialist system in which currency has been abolished and yet everyone works in harmony for the betterment of society.

The Federation is a post-scarcity society (not 'socialist') in which basic needs are met easily and work is geared more toward more cerebral tasks. Currency is 'credits' and is used largely in artisanal transactions.

Balkanization may be the only proper way out of all this.

If one has a skillset, get out of the city/suburbia now.

Shelter, water, food, energy, clothing, tools and a means to protect them.

Chumby!! You had us worried, great to see ya!

Yep! The gang's all here now! It'll be much more fun!

Balkanization?

Going Grizzly Adams does not necessitate ethnic/racial division or hatred. And with the Information Age technology of today, one could enjoy the best benefits of Cosmopolitan cities like culture, education, entertainment, and commerce without the dysfunction, crowding, crime, and filth.

Proposed in the twilight years of our collective love affair with urban utopianism, the park was opened in 1982. But for the next 40 years, when cities of tomorrow came up at all in culture, they were invariably dystopian, from the rampant crime of RoboCop's Detroit to the casual traffic violence of Akira's Neo-Tokyo. Until quite recently, urban settings were so central to dystopian fiction that entirely new cities were often invented to host them, as with Cyberpunk 2077's Night City, or Ghost in the Shell's New Port City.

Conspiracy Theory: The original Batman's real alter ego was Walt Disney. Until Disney's death, Gotham was populated by a truly colorful, motley group of criminals but was still, largely, a pretty nice place to live. The criminals pretty strictly stuck to robbing banks, extorting the Mayor, and doing the Batusi. All crimes were solved in a half hour, or less, after the Mayor picked up the batphone and a kid-friendly fisticuffs ensued. It wasn't until after his death that escalation began and Gotham really went downhill.

*Pow*

*Kayo!*

*Kick!*(From Batgirl!)

The sight of Spandex, Lycra, Leather, Pleather, and PVC formed skin-tight on fit, alluring bodies in motion sure did give a wonderful high to a 6-year old boy long ago! 🙂

Good article.

“After a century of fantasizing about what it would be like to have technocrats set the terms of urban life—or fretting about what might happen if they don't—perhaps it's time for a city of tomorrow that lets individuals plan for themselves.”

This is why socialism inevitably fails. People think that they are smarter than human nature, and impose their will over others to gain their own vision of utopia. Socialism is about power. The more people you get close together, the more power you have, the more money that you can skim for yourself and your cronies.

For centuries we had been moving towards more and more centralization because of efficiencies of scale, esp in business and manufacturing. Except that we have gone too far. If you pack too many rats together, too closely, they turn dystopian too, with juvenile gangs terrorizing the community, and the like. Humans did not develop over the millions of years of our development to live this closely packed together. You go back a mere hundred generations, and much of the world’s population wasn’t living that much differently than our chimp ancestors did millions of years ago, and do today, in terms of density. Two hundred generations, and almost all of humanity was living highly dispersed in small communities.

We found during the recent pandemic that much of the population concentration we see in esp urban centers is no longer really needed or efficient. This means that the natural result will be to disperse. Maybe a little. For many of us, a lot. Walking the dog every day, in tune with nature, really is therapeutic, at least for me. That’s where I think that we are headed. Yes, there is resistance, esp by leftists and leftist politicians who see their power heading to the countryside, where they can’t control and exploit it. In the end, the tighter they hold onto the past, the faster the people who can, will flee.

Personally, I prefer to sit on the back porch with a cup of coffee watching the dog run in the yard. No leash.

The fence is to keep others dogs out, not him in.

The real problem with cities is that their assets are often their liabilities. As the number of people and area grow it becomes harder to get consensus on things. People want to deal with the homeless but don't want the shelter near their neighborhood. They want mass transit but seem to use their cars for every errand. Living together in the world, the country, the state and down to the city requires compromise that seems to be in small supply. My problem with my own city is less with crime and homelessness and more with the fact that no decisions can ever be made. Opportunities are lost because they require change or require politicians to make hard decisions.

"Everyone" (liberal) wants mass transit _for other people_. They want the masses to ride the trains and buses and leave the roads clear for their cars.

This is because mass transit inherently sucks. It doesn't go from where you are to your destination, but from stop to stop, leaving you to walk the rest of the way - often out in bad weather, at risk of muggings, adding considerably to your travel time, and making it quite difficult to bring home groceries or carry anything larger than a backpack. It crams you into a metal tube with strangers, and then uses up more of your time when you wait while they get on and off at other stops. Except for large and very dense cities that lack the space for an adequate street grid and have sunk fortunes into subways, it is much slower than driving - and cities that are dense enough for subways to be affordable are too dense for your mental and physical health.

One thing is for sure... City governing should remain COMPLETELY inside city limits and not suck off the National Gov-Gun theft tit. Seems the only Utopia trying to get built is massive armed-theft for Nazi(National Sozialism)-Project #1578349.

Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow — invite visitors to imagine a world of technological progress, centralized planning, and scientific management.

Sounds like Beijing, with high ticket prices.

Ticket prices, true. But you don't have to pay, it's your choice, unlike taxes.

Within cities, technological "progress" is depicted as sending every social problem into overdrive, from drug addiction to sexual depravity to social isolation.

Depicted? I live in it, for chrissakes.

At least through the early 2010s, zoning rules continued to tighten and urban freeways continued to widen. Today, you can barely ride an electric scooter across most cities, let alone a flying car. Many American cities ended up with cyberpunk problems—homelessness, inequality, sprawl—but without any of the compelling cyberpunk aesthetics

Just so you know, the cyberpunk genre isn't really about the failure of urban planning (although that might be one splinter in the woodpile), the cyberpunk meta is about an advanced technological society that is in decline. The "compelling cyberpunk aesthetics" wouldn't really be that compelling if you lived in it. This is why people get confused about what Cyberpunk is. They think the technology is "cool" and would be a fun, anarcho-capitalist place to live.

Making travel difficult for electric scooters is good urban planning.

Especially Biden's, Man! 🙂

How can you write an article like this and not mention the utopian city being built in Saudi Arabia right now - The Line?

I mean, it's probably not going to pan out, but its existence (or attempt at existence) pretty much undercuts the point of this article.

The Blade Runner of that city will go after Apostates and Blasphemers.

The real question is how come no city has ever planned for slums yet every city has them.

No modern city. Ancient cities always included slave quarters.

I am not sure slave quarters are the same thing as slums, in fact I would claim they are not. In many cases slaves lived in the house/estate of their owner. Not saying they lived in the same level of quarters as their owners but I would not say they were slums. This link may be of interest.

https://en.subalternosblog.com/post/the-slums-of-ancient-rome-words-and-things

I've seen buildings behind old homes that used to be slave quarters. Ramshackle and creepy and definitely worse than many slums, though slums can have buildings like that too.

The difference between slave quarters and slums is that slave owners kept the workers they owned close, so the slave quarters were ramshackle buildings amidst the much better buildings of the owners. Move hundreds of slave quarters off the estates of the wealthy and cram them side by side in one neighborhood and you have a slum - and that is much worse because it concentrates all the social problems of the poorest workers into that neighborhood.

You know who else tomorrow belongs to?

The Mutants.

In that case tomorrow has arrived here in California, baby! Tomorrow is HERE!!!

Since they repaired the Comments from last night, tomorrow belongs to you and Chubby! And you don't need some pasty-faced, brown-shirted Bowie Mini-Me to proclaim it either. 🙂

I meant Chumby! Damn AutoCorrect!

The city of tomorrow should be more like the city of Irvine, California, run by the Irvine Company. And with the lowest crime rate of the 100 largest cities in the USA.

Oh the irony!

The city of the future (10-30 years out) will be built around AI, AR/VR, driverless vehicles, universal basic income, and abundance.

At some point, ten years or fifty years, we will have precision fermentation that lowers the cost of food by 90%, higher yield solar, and 3x density and cost-effective batteries that will lower energy and transportation costs by 70%. At that point we can provide a UBI as a replacement for our Great Society spending at a lower cost.

Those who want will be able to be anyone, and live any life they choose in VR. Those who want to do more will be able to do so.

The result of all of this is the ability to live wherever you want with easy access to outdoors. Therefore the city of the future is built upon a 3-7 story downtown area that is accessible by bike path, driverless shuttle, or walking with shops and restaurants and entertainment. Your home and neighborhood will be able to access outdoor amenities out your back door. People will migrate to areas that best fit their idea of where they want to live rather than large cities required for work. Some people will still want to live in large cities for the energy and the social scene.

We've seen through the COVID-19 "stimulus" checks just a small fraction of what UBI would do to supply chains and the price of goods. With full-bore get-paid-to-exist UBI, none of that shit you talk about would be affordable or even fiunctioning once rioters and vandals bored by idleness got a hold of them. No thank you!

By the way, is your name Franco? I keep hearing you're dead.

Cities and Towns without murderer Police, domestic abuse among neighbors, Counsel members who make phony Facebook accounts to insult citizens, and Treasurers who abscond with the Town Treasury every so often would be nice. Regardez!:

Off-duty Ranlo Police officer accused of killing unarmed man

https://www.gastongazette.com/story/news/crime/2023/01/04/ranlo-police-officer-accused-of-shooting-unarmed-man/69776803007/

Starring Anthony Fauci?

I never figured he could read - - - - -

I earn $100 per hour while taking risks and travelling to remote parts of the world. I worked remotely last week while in Rome, Monte Carlo, and eventually Paris. I’m back in the USA this week. I only perform simple activities from this one excellent website. see it,

Click Here to Copy…… http://Www.Smartcash1.com

A Hallmark movie from hell.

Chipping wood.