The Case for Space Billionaires

What critics of the private space race get wrong

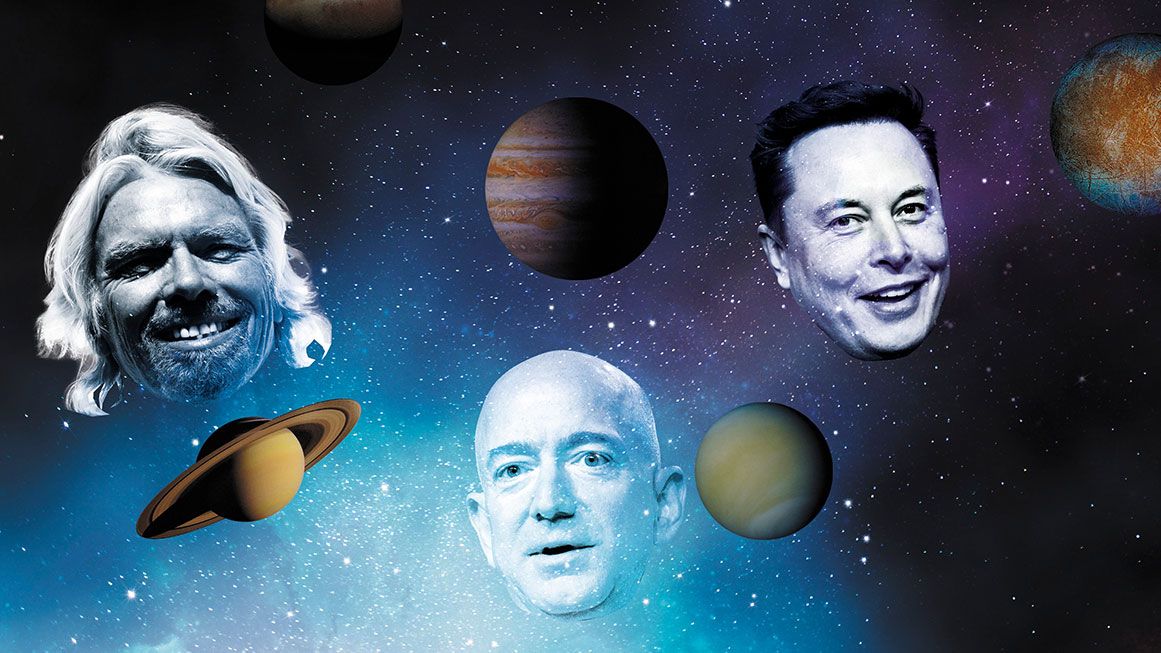

Statistically, Americans love space. Anecdotally, they hate it when billionaires go there. Majorities of all parties, genders, and geographies tell pollsters they support U.S. missions to the moon and Mars, and three-quarters say that the effort to land the first men on the moon was worth it. But last year, when the big three spacefaring billionaires—Virgin's Richard Branson, Amazon's Jeff Bezos, and Tesla's Elon Musk—managed successful manned missions in rapid succession, Twitter (and Congress) were bursting with rage.

Every corner of the internet was filled with the same hot takes. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I–Vt.) made a choleric announcement, for example, that "it's time to tax the billionaires" because "here on Earth, in the richest country on the planet, half our people live paycheck to paycheck, people are struggling to feed themselves, struggling to see a doctor—but hey, the richest guys in the world are off in outer space!" This tweet from a self-described anti-capitalist went viral: "I actually don't think we're angry enough about rich people going to space while the world burns." Another Twitter user requested in poem form that "perhaps billionaires/Could solve problems on earth/Rather/than race to space/For their egos." There were also an astonishingly large number of dick jokes.

But the case against space billionaires falls apart on closer scrutiny. At worst, the private space race is no more frivolous or wasteful than other, more mundane business, philanthropic, or government projects. At best, what began as a luxury pursuit opens a new frontier and kick-starts a new industry that will dramatically expand humanity's prospects.

Earth First

Let's begin by addressing the most common and perhaps the most defensible objection—call it the "there are problems here on Earth" complaint. This is the idea that space travel is difficult and expensive, and that the resources billionaires are using to leave the planet should be used instead to improve life here first.

The concern makes intuitive sense, and it's not a new argument. Even the Apollo program was rather unpopular in its early days—when government space ventures were the only game in town—with only 22 percent of Americans agreeing that there was a "great and urgent" need to get to the moon in 1962. Gil Scott-Heron's 1970 poem "Whitey on the Moon" laments the misuse of resources in the face of poverty and racial injustice (and complains about the taxes that take his "whole damn check" while he's at it).

Money is fungible, so every dollar spent on space is, indeed, a dollar not spent elsewhere. But investments in the space sector total about $264 billion, according to Space Investment Quarterly, with the vast majority of that figure going toward satellites. Satellites tend not to elicit the kind of ire that still-rare private manned space travel inspires, perhaps because their utility to ordinary people for telecommunications and GPS is already well demonstrated. Though the falling price of putting up a satellite is closely intertwined with billionaire space ventures, we'll set that spending aside. The roughly 115 companies involved in launch, including the billionaire boys' space jaunts, represent a total investment of $25.9 billion. Not chump change, but also not enough to definitively end poverty, injustice, or other terrestrial troubles if the problem was really just simple lack of funds.

Embedded in the "problems here on Earth" complaint is the odd assumption that spending on space projects shows a lack of care about any other effort to improve humanity's lot. In fact, the billionaires involved in the private space race have given far more money to charity than they have spent on space. Bezos gave $10 billion in 2020 alone to fight climate change and more recently donated $100 million to José Andrés, whose World Central Kitchen seeks to relieve global hunger. Tax disclosures from Elon Musk—who helps support Doctors Without Borders, educational charities, and environmental groups—reveal that he gave away 5 million Tesla shares last year, making him the second biggest charitable giver overall.

There also are plenty of major philanthropists who simply aren't very interested in space, Bill Gates first among them. When interviewer James Corden asked him about his spacier billionaire brethren, Gates replied: "Space? We have a lot to do here on Earth." Corden dubbed Gates' response the "classiest burn," but the distance between Gates' position and Musk's seems less substantial than interviewers looking for drama would prefer.

Musk in fact agrees that most of Earth's resources should be used to resolve the issues plaguing our world. "I think we should spend the vast majority of our resources solving problems on Earth. Like, 99 percent plus of our economy should be dedicated to solving problems on Earth," he said in the documentary Countdown: Inspiration4 Mission To Space. "But I think maybe something like 1 percent, or less than 1 percent, could be applied to extending life beyond Earth."

Similarly, Bezos said shortly after his spaceflight that his critics were "mostly right." But "we have to do both. We have lots of problems here and now on Earth and we need to work on those and we also need to look to the future, we've always done that as a species and as a civilization."

Even the skeptical rich may be drawn into the billionaire space race in the end: Stoke Space, a new company founded by Blue Origin and SpaceX alums, promises a greener, 100 percent reusable rocket. It recently received $65 million in funding from Breakthrough Energy Ventures, part of a network of organizations called Breakthrough Energy, which was founded by…Bill Gates.

Tax and Spend

Bernie Sanders did more than call for the space billionaires to do better or different philanthropy—he called for taxation. This critique of the space billionaires is less about the efficacy of their altruism and more about whether space launches are merely reminders that they are not paying their fair share in taxes.

Even if all the resources that went into private space were rendered unto Caesar, there's no particular reason to think they'd be put to better use. Governments don't have a great record of using marginal funds to help the least well off, and there's good reason to think it would be squandered for even less good, and perhaps even for things that are actively bad, in government hands.

To Sanders' credit, some of his follow-up tweets after the billionaire launches were more on point. In April, he tweeted: "At a time when over half of the people in this country live paycheck to paycheck, when more than 70 million are uninsured or underinsured and when some 600,000 Americans are homeless, should we really be providing a multibillion-dollar taxpayer bailout for Bezos to fuel his space hobby?" While the taxpayer money paid to Bezos' Blue Origin under a bill crafted specifically to channel $10 billion through NASA to the company was almost certainly used more efficiently than other space funds allocated to the space agency, this is a fair question.

Still, this particular argument sits oddly against the general public's willingness to support government-funded space travel. If it's permissible, even patriotic, to spend billions of taxpayer dollars on space exploration and travel, surely we can allow a small group of wealthy people to spend their own money on the same project?

Competing Visions

Perhaps Americans like the idea of space exploration but think there should be only one player, and that this player should be a government, ideally the U.S. government. There are a few flaws in this line of thought. For one thing, that cat is already out of the bag. There are several spacefaring nations on Earth with competing programs already. Prior to the success of the billionaires' companies, the U.S. was dependent on Russian Soyuz rockets to get off the planet and meet its obligations on the International Space Station (ISS). In light of current tensions with Russia, it's lucky we have a U.S.-based private alternative—and that other nations with space aspirations do as well.

Not all approaches to space exploration are equal. The billionaires are not duplicating each other's efforts; each is building different tech to pursue different goals. This characteristic of competitive marketplaces has served consumers well when it comes to cars, snacks, and phones, so it's no surprise it would happen in the space sector as well once entrepreneurial private actors are involved.

The first billionaire to make it to space himself, Richard Branson, flew on Virgin Galactic's spaceplane Unity. His vehicles are heavily reliant on skilled pilots, and—like his other ventures—Virgin Galactic focuses on providing an exciting experience with excellent customer service. Jeff Bezos followed shortly thereafter in his own New Shepard space capsule. Blue Origin's vehicles can fly without pilots at all and are designed to be highly standardized, not unlike the standardization and automation model that has made Amazon a success. While Elon Musk himself has not yet flown in his SpaceX Dragon spacecraft, many commercial passengers and paying spacefarers sent by their various governments already have; Musk is the farthest along in growing a viable commercial enterprise.

Musk and Bezos have competing visions for humanity's post-terrestrial future, with Bezos envisioning a complex of interconnected satellites in orbit and Musk preferring a more classic Mars colony plan. (Branson, for his part, presents a simpler but no less compelling tourism-centric vision for space. It can be summed up as "Woooo!")

Don't Give Up

A variation on the "we have plenty of problems here on Earth" critique is the "don't abandon Earth" plea. While Musk has famously said that he hopes to die on Mars, he's been quite clear that he'd love to take as many people to the planet as would like to join him. In fact, Musk has explicitly said his goal is to plant "enough of a seed of human civilization to bring human civilization back."

The critics' concern seems to rest on the mistaken belief that the space billionaires are Marvel supervillains who are only one monologue away from revealing that they have each built exactly one ship which they plan to fly to their secret moon bases where they will cackle as humanity slowly roasts, starves, or blows itself up.

Bezos has likewise been clear that his desire to further spaceflight is not about escape but about the improvement of the human condition, including for those who remain on Earth. "We can have a trillion humans in the solar system," Bezos declared at a 2019 announcement about Blue Origin's plans to build a moon lander. "Which means we'd have a thousand Mozarts and a thousand Einsteins. This would be an incredible civilization."

Maybe they're full of beans. It's entirely possible all the grand talk is just rationalization by little boys who want to ride on the rockets they dreamed of in their youth. The beauty of functioning markets, though, is that sometimes they take one person's frivolous dream and make it come true for tens or hundreds or millions of people who, it turns out, share the same dream.

Perhaps spaceships really are just the next thing to buy once you're tired of your yacht and private plane. Maybe the space billionaires are foolish men who want only to compete with each other at a (literally and figuratively) rarefied level beyond the reach of mere mortals.

If so, one might argue that what billionaires need is some perspective. Luckily, we know of one surprisingly effective way to generate a deep and profound shift in mindset.

A New Perspective

Nearly everyone who has viewed the Earth from space reports a similar experience: one of awe, tenderness, and protectiveness toward the planet and her inhabitants. They almost universally find the experience deeply affecting, even life-changing. Whole Earth Catalog's Stewart Brand, who hasn't made it to space yet, understood the power of this insight and made it his mission to procure a photo capturing that perspective from NASA's files and disseminate such imagery as widely as possible.

The "blue marble" photograph of the disk of Earth was taken by the crew of Apollo 17 almost exactly 50 years ago. They were on the final manned mission to the moon. They were also the last crew to get far enough from home to take a true whole Earth photo.

Upon his December return from a 12-day mission to the ISS, arranged by the tourism company Space Adventures, the Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa said going into space and looking back at a view he found "100 times more beautiful than photographs" made him "obsessed with the Earth." He plans to take a small group of creative minds with him on a SpaceX mission to fly around the moon in 2023 at his expense because he believes the work they will do in space and after the fact is crucially important to humanity.

"You begin to think about world leaders getting together in space," he said in a press conference. "Of course, I'm not a powerful enough person to make it happen. But if it did, the world might be a better place to live."

For those concerned about the power and vast resources controlled by billionaires, a good long look at the blue marble could be just the thing to help clarify and distill what really matters. And the rest of us might benefit as well, when our time comes to fly.

"To see the Earth as it truly is, small and blue and beautiful in that eternal silence where it floats," wrote the Apollo-era poet-journalist Archibald MacLeish, "is to see ourselves as riders on the Earth together, brothers on that bright loveliness in the eternal cold—brothers who know now that they are truly brothers."

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "The Case for Space Billionaires."

Show Comments (26)