Yes, You Can Yell 'Fire' in a Crowded Theater

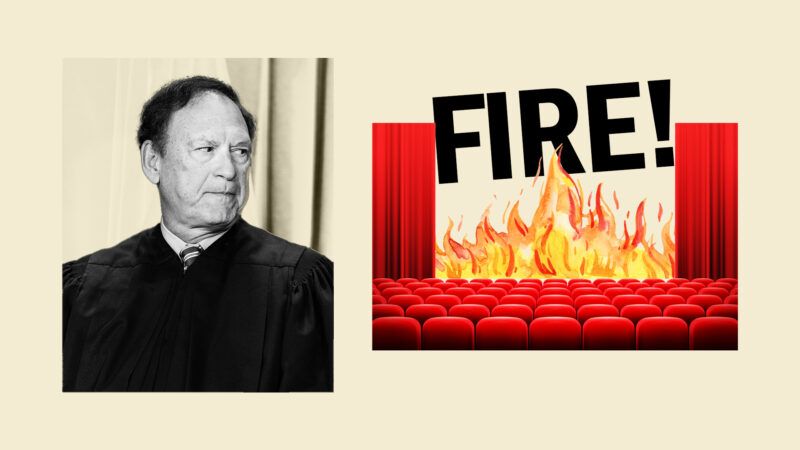

On Tuesday, Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito repeated the common myth that "shouting 'fire' in a crowded theater" is unprotected speech.

Though it is a popular misconception, it's perfectly legal to yell "fire" in a crowded theatre. However, Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito hasn't seemed to have gotten the message.

Despite sitting on the highest court in the land, directly deciding what is—and isn't—protected by the First Amendment, Alito delivered repeated on Tuesday a common constitutional myth. Whether the remark reveals a deep-seated misconception about First Amendment jurisprudence or was simply a momentary slip-up is unclear.

On Tuesday evening, Justice Alito, delivered remarks at The Heritage Foundation, as part of the think tank's Joseph Story Distinguished Lecture. During the lecture, Alito spoke on a wide swath of issues—ranging from his early legal career to substantive due process. He also expounded at length on the state of discourse and free speech on college campuses, particularly law schools.

"Based on what I have read and what has been told to me by students, it's pretty abysmal, and it's disgraceful, and it's really dangerous for our future as a united democratic country," Alito said. "We depend on freedom of speech. Freedom of speech is essential."

Alito emphasized the particular role that law schools have in fostering "rational debate" and holding firm to the principle of free speech, saying that some schools were "not carrying out their responsibility."

However, Alito's trouble began when he was asked where he would "draw the line between protected and unprotected speech." Alito emphasized the importance of protecting "any speech involving public issues, involving politics, government, history, economics, law, science, religion, philosophy, the arts," but he noted that the First Amendment doesn't protect all speech, including "extortion and threats," defamation, and "shouting 'fire' in a crowded theater."

However, Alito is simply wrong that "shouting 'fire' in a crowded theater" is unprotected speech. The erroneous idea comes from the 1919 case Schenk v. United States. The case concerned whether distributing anti-draft pamphlets could lead to a conviction under the Espionage Act—and had nothing to do with fires or theaters.

In his opinion, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote that "the most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic." However, this idea was introduced as an analogy, meant to illustrate that, as Trevor Timm wrote in The Atlantic in 2012, "the First Amendment is not absolute. It is what lawyers call dictum, a justice's ancillary opinion that doesn't directly involve the facts of the case and has no binding authority." The phrase, though an oft-repeated axiom in debates about the First Amendment, is simply not the law of the land now, nor has it ever been—something made all the more apparent when Schenk v. United States was largely overturned in 1969 by Brandenburg v. Ohio.

"Anyone who says 'you can't shout fire! in a crowded theatre' is showing that they don't know much about the principles of free speech, or free speech law—or history," Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression President Greg Lukianoff wrote in 2021. "This old canard, a favorite reference of censorship apologists, needs to be retired. It's repeatedly and inappropriately used to justify speech limitations."

While Alito's mistake is a common one, it is particularly frustrating because, as a Supreme Court Justice, he should know better. The popularity of this myth poses real threats to free speech. "You can't yell 'fire' in a crowded theatre," is often invoked to justify unconstitutional restrictions on speech and to overstate restrictions to the First Amendment. When this myth is adopted by a Supreme Court Justice—no less, the lone dissenter in two recent 8–1 First Amendment cases—it spells danger for our broader cultural understanding of free speech, as well as the values held by those in power.

Show Comments (108)