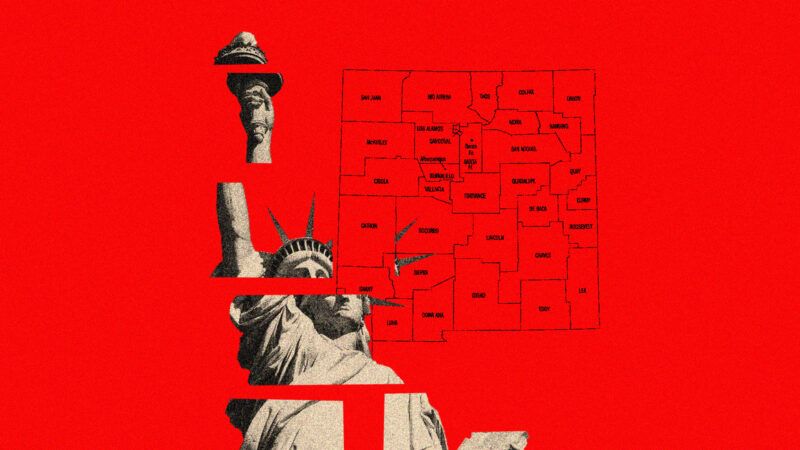

Libertarian Party Faces State Rebellions

The Libertarian Party's state affiliates in New Mexico and Virginia have broken away amid ideological and procedural turmoil—and the Virginia branch may have dissolved entirely.

Upon taking control of the Libertarian Party (L.P.) this May, leaders from the internal bloc known as the Mises Caucus quickly adopted "national divorce" as one of the retooled party's core rallying cries on Twitter. New national Chair Angela McArdle proudly tweeted that she was "organizing the LP like an insurgency and preparing for counter insurgency operations."

Over the past three weeks, minus the bloody violence part, the state Libertarian affiliates in New Mexico and Virginia have indeed divorced themselves from the party's national leadership. But the Libertarian National Committee (LNC) is not letting them go peacefully without a fight.

On August 25, the Libertarian Party of New Mexico (LPNM), which achieved major-party ballot-access status in 2018 thanks to the 9 percent presidential showing in 2016 in that state by former two-term Gov. Gary Johnson, announced that it was disaffiliating from the LNC.

"You have conspired, with a faction inimical to the principles of libertarianism, to impose upon us officers and governing documents foreign to our rules, unchosen by our members, and unacknowledged by the laws of our state," state Chairman Chris Luchini wrote, in a long bill of particulars. "You have adopted messaging and communications hostile to the principles for which the Libertarian Party was founded, serving no purpose other than to antagonize and embarrass."

At issue was an August 9 LNC letter declaring the New Mexico state party's July 12 Constitutional Convention to be "null and void" due to "multiple" procedural violations, involving the proper advance notice and the manner of the convention (electronic). In a phone interview last week, Luchini theorized that the LNC's real objection was to a bylaw change the LPNM made at that convention limiting the number of annual executive committee personnel changes to not more than two, thereby preventing the Mises Caucus (or any other bloc) from winning complete control of the state party in a single convention.

While Luchini granted procedural errors over advance notice on an earlier convention prior to the July one, he said the LNC's responses have been unduly and unreasonably punitive and harassing.* "Violate a procedural rule, God forbid, commit heresy against Robert's Rules of Order, they think us making a mistake justified any action on their part." Rather than submit to national discipline, the LPNM chose secession.

No, we break up with you, the LNC responded in a meeting this past Sunday night. The National Committee refused to recognize the LPNM's right to exit, and instead voted 14–1 (with two abstentions) to disaffiliate itself from the New Mexicans. But this divorce will come with a likely custody battle—over the name.

"If state parties choose to disaffiliate and operate completely independent of the national LP," McArdle wrote to me this week, "they will need to come up with a new name."

Luchini, for one, finds it ironic that the LNC is threatening to sue—use state force—to protect its trademark over the term "Libertarian Party,"* especially considering that the LPNM had been in operation for decades before the LNC got around to trademarking the term in 2000.

The LNC anticipates that a new group of New Mexico Libertarians—the national party bylaws require just 10—will arise to form a new state-level L.P. in New Mexico that the LNC will then recognize as an official affiliate. But the existing ballot access relationship with the state of New Mexico remains with the disaffiliated party for now. According to a special rule of order passed at that same LNC meeting Sunday night, "The petitioners [for such a new party must have] held a public meeting which was open to all current national Party members and immediately previous affiliate Party members," with reasonable notice.

That same day, the Virginia Libertarian Party's state central committee (SCC) announced that it had dissolved itself after a 7–5 vote (with one abstention), complaining that "the national image of the party" was now "functionally indistinct from other alt-right parties and movements." The party's website and Facebook page disappeared; its email addresses stopped working.

The move was illegal, LNC Secretary Caryn Ann Harlos says, though the Virginia State Corporation Commission issued a letter Tuesday stating that the dissolution complies "with the requirements of law." A parliamentarian consulted by the LNC countered that the dissolution required a vote of full party membership, while now-former Virginia L.P. chair Holly Ward believes that the SCC itself is the only relevant "members" who needed to approve. McArdle also said in a post to the LNC's business listserv that "corporate dissolution papers do not make or break an affiliate and lots of affiliates don't have corporate status." Technically, in Virginia another legal step known as "termination" must also occur, after the Virginia party's assets have been properly distributed.

Ward charged in a phone interview that the LNC has become a "fraud," properly backing neither Libertarian candidates nor Libertarian messaging, in a state whose party achieved a remarkable 6.5 percent running Robert Sarvis for governor in 2013 (and another exceptional-for-Libertarians 2.4 percent running Sarvis for Senate in 2014). The national party has made the Libertarian banner toxic to potential candidates, Ward claimed, which she thinks helps explain why there are no L.P. candidates on Virginia ballots this year. In doing candidate outreach, Ward says, she found "interested parties declined to run based on the current image and narrative of the national party."

Several local and regional Libertarian organizations in Virginia objected to the SCC's abrupt self-destruction, and the conflict is ongoing: Disgruntled Virginia L.P. members are being asked to write letters of complaint to the state government (a move Ward considers a potential use of state force to achieve a political goal, and thus a Libertarian no-no), and the Libertarian Party of Northern Virginia has been decrying the move and vowing to "continue to work with affiliates across the Commonwealth to conduct the business of the party," state party dissolution or not. There are various means for members to call for a new special convention and elect new officers who don't want to dissolve, Harlos says, working on the presumption that the dissolution motion should be considered illegitimate.

"While the LNC has had to referee some internal party disputes recently," McArdle wrote in her email, "we're still focused on advancing the message of liberty, supporting candidates, and moving the needle in the direction of freedom. I appreciate how level-headed and calm the remaining LPVA officers have been and anticipate they will get their affiliate back in order quickly."

Virginia and New Mexico are not the only states experiencing Libertarian turmoil. Massachusetts now has two functioning parties using the name Libertarian, only one of which is recognized by the LNC.

The Bay State fight emanated from a Mises-associated bloc of members from the state party calling for a (bylaw-legal) special convention in December 2021, that the old guard attempted to quash in January 2022 by expelling from the party all who called for it. Competing conventions were then held in April and the newer, Mises-oriented bloc is the one the LNC now recognizes as an affiliate.

Still, all the Libertarian candidates on the Massachusetts ballot this year are the ones put forward by the older body, doing business as the "Libertarian Association of Massachusetts." Andrew Cordio, chair of the officially recognized "Libertarian Party of Massachusetts," said in a phone interview this week that he's currently more focused on membership and volunteer growth and outreach than candidates and ballot access.

In 2021, the Mises Caucus faction, then influential but not dominant on the LNC, was on the opposite side of a state-disaffiliation case, successfully blocking a move to break ties with a New Hampshire L.P. that was seen by the old guard as being too "toxic" for the national brand. (Roughly, some accuse the Mises side of hypocrisy, seeing the current New Mexico situation as analogous, except now the Mises crowd are for disaffiliating a state party that displeased them.) The attempted purge of the New Hampshire party, which has since attracted national attention for various inflammatory tweets, led directly in June 2021 to the resignation of then–national Chair Joseph Bishop-Henchman.

Harlos, consistently the LNC's most meticulous stickler for proper parliamentary procedure, explains that the national party is duty-bound to protect the rights of members, sometimes over the actions of their governing bodies. If the LNC seems to be interfering with a state party, she says, it's because "we have to determine who [the legitimate state affiliate] actually is," which has to include "if they conducted themselves within their own bylaws."

The LNC may be exerting a heavy hand of late in publicity and state affiliate management, but on the issues core to the functions of a political party—ballot access and candidates—the national party is largely irrelevant; the state parties do all the heavy lifting and have the legal relationships to their state's electoral officials. The national party's role is to occasionally offer financial, legal, promotional, and organizational support to either ballot access drives or (more rarely) candidates or candidate training.

The national party does pick a presidential ticket by majority delegate vote at its biannual convention in presidential election years, but every state affiliate has the legal power to ignore that choice and place its own preferred candidate. It almost never happens with any state party in happy affiliation with the LNC, but a rogue Arizona L.P. in 2000 did place science fiction writer L. Neil Smith on the presidential ballot in that state over national choice Harry Browne.

It seems overwhelmingly likely that whoever the Libertarian presidential nominee selected by the national convention delegates is in 2024, he or she will not be on the ballot in all 50 states, a threshold that the L.P. has achieved the past two presidential elections and six times total in its 50-year history.

Despite these state conflicts, including assertions that current national policies are hurting the brand, according to its August financial report the national party's number of active donors did begin rising after the May convention turnover in management, though as of August that number is lower than in any month in 2021 under the leadership displaced in Reno; August revenue is lower than the vast majority of months of the past year after a huge May rise that beat all but one month of the past year.

Luchini in an email this week said that there are plans to launch a new national organization of state Libertarian parties that do not wish to be affiliated with the current Mises-dominated LNC. While Luchini would not name any states specifically, he says he is confident from backchannel discussions that while New Mexico was "the first" to disaffiliate while still being recognized by the LNC, it certainly "won't be the last."

*CORRECTIONS: A previous version of this article was unclear about which convention Luchini granted notice errors on. A previous version of the article was unclear about precisely what term was trademarked by the LNC.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

[insert something clever about herding cats]

Nothing more irrelevant than libertarians.

So much better to choose a winning team and give up all of your morals, principles and beliefs than to be a loser. Especially because it feels so good to around taunting losers by calling them losers because they're losers. Who needs a conscience when you can be a total asshole, right?

So much better to choose a winning team and give up all of your morals, principles and beliefs than to be a loser.

Then, presumably, you agree that the whole "pragmatist" charade within the Libertarian party was a disgraceful and morally bankrupt abandonment of libertarian principle to progressivism. It's good that you're finally coming around to see that the Mises caucus are the good guys in this fight and not those seeking to water down libertarianism to make it more palatable to cosmopolitan progressives. Now, if we could just convince the writers here.

I've never really given two shits about the Libertarian Party. I'm a libertarian, not a Libertarian.

Cite? I mean anyone who supports the murder of an unarmed woman can't be libertarian. You choose your application of principles based on politics.

But she was trespassing! And a traitor!

I was excited to find an actual libertarian rather than unperson masked sockpuppet. But the link returned: "dc.libertarianparty.com took too long to respond." I get 0.03 sec for my distance from DC over c. Maybe cables slow things down...

Try our substack.

It's free this month!

https://dclibertarianparty.substack.com/

You are neither. Your still in the closet about being a Progressive.

I bet you still call people "fag."

Been itching to say that word have you?

Say it to Herr Misek—that will create quite a Storm.

Why are you being such a fag to him?

I prefer "queer" now that it's become politically acceptable? again.

Umm, pragmatism is pragmatic.

Allying with conservatives serves no pragmatic goal of a libertarian.

Or I should have said modern Trump conservatives, who are not like traditional conservatives at all.

Even when he was lowering taxes, passing the First Step act, and not starting any new wars?

Plus all the deregulation. Including his requirement that to pass a new regulation, two old one must be eliminated.

Mike wants the libertarian neocons back.

Yes, they appear to actually want to dismember the surveillance state.

How gauche!

You can't get a new job at Brookings after being a Cato intern if you are seen with those people.

Allying with conservatives serves no pragmatic goal of a libertarian.

So, White Mike is insisting that libertarians should give up their principles in pursuit of...something. But, only when dealing with progressives. There's never any reason for libertarians to make common cause with those icky Republicans. But, don't ever question for a second whether White Mike is a progressive hack.

muting you

You realize this is just more evidence for his claim that you're a progressive hack right?

If you're gonna mute, mute. Don't talk.

"Allying with conservatives serves no pragmatic goal of a libertarian."

It's true, there is zero record of one side winning wars and public policy by forming coalitions with (imperfect) allies. The key to victory is just simply sticking by your principles.

Oh, White Mike would be more than happy to see libertarians abandon their principles. In favor of the wants and desires of progressives. Because he's a progressive hack.

True. Though by 1980 the same thing had happened with the Dems. That party was completely absorbed--not by Bellamy-Bryan-Howells--communists but by YIP-Weathermen-Soviet Trilby infiltrators. The shocking part is that the Weathermen, who sprang Tim Leary from the pen and invented "advance notice" bomb threats, more closely resembled Ayn Rand than anyone else in the fistfight. The existence of the LP was memory-holed, censored, elided, not fit to print. Anarco-communist infiltrators as soi-disant libertarians made the GOP look good by comparison to themselves or Dems. Chomsky best exploited intrincisism as a moral basis for the new totalitarianism.

People can pretend the Mises Causes isn't a bunch of crypto-racists, but nobody is fooled.

Yes, the fact that some of them are black, or gay, or women and that they name themselves after a Jewish refugee from Nazism is proof enough!

Maeces Caucasians are Trumpanzee throwbacks to Teedy Roosevelt, just as Adolf Hitler was a throwback to Teedy Rosenfeld and his buddy Kaiser Wilhelm. See 20 April 1934, Spokane Daily Chronicle P.49/60 Famous "Lost Interview" of Kaiser Wilhelm. It is online in the Google News Archive. If you can't find it, I'll be blogging it soon. If I were Republican I'd've had Trumpanzees swarm the LP just like ANTIFA Dems had their anarcho-minions swarm the LP after Gary got 4 million votes and switched 13 states.

You know, contrary to what you've been told, libertarians don't all approve of public drug usage.

You dont have any principles.

He’s does have one. He hates Trump. That is the overriding principle in his life. That anything he does or says must be in the furtherance of expressing hatred towards Trump and anyone who supports and/or agrees with Trump.

He’s also a severe alcoholic.

Fair.

Why not - that is what you did.

People that have a conscience don't become libertarians/Libertarians, so I'm not sure why you think that's relevant.

Cite?

Hahahahahahahahahahaha

No.

So... wat chOO doin' here, white lamb?

The only aspect of this comment that disabuses me of the notion that you actually write for Reason is the fact that it overtly implies the Republican Liberty Caucus and Mises Caucus are equal cats.

Libertarian organizations can't exist without living off corporate handouts in exchange for creating and distributing pro-corporate anti-democratic propaganda. AKA Fascist propaganda.

I have never encountered a Libertarian who wasn't a congenital and perpetual liar.

Never.

Well, everyone now knows you are a complete idiot and doesn't need to read your posts.

I doubt you are even one of the ubiquitous DC hos who is paid to write this drivel by the actual corporate donors who fund the Democrats.

You don't sound smart enough to even be one of those streetwalkers.

Mr Chekov, deploy Moot Lewser on District of Columbia impersonator...

I have never encountered an anti-Libertarian who wasn't a congenital and perpetual liar.

Ah! A vendisold sock brainwashee to teach us that freedom is the initiation of force rather than the absence or minimization thereof.

Engage Moot Lewser! Mr Chekov, fire when ready.

Apparently this author didn't interview any of the cats, ut simply relied on a couple of press releases.

If you live near Virginia, and I imagine if you live near New Mexico, you can find a lot of LP members discussing these actions, and the picture you get is very different from that of this article.

Mild annoyance for the LP not being unified? If you watch the Committee meetings they have been at each others throats for years now? It is like anything though? If you actually look at LP policies? They are better then either of the two other parties?

Much freedom much liberty meanwhile congress and both the presidents from the last 8 years have had a 30% approval rating on a good day? Act like Americans care about anything but just winning? It is a fault in this country where they don't look at policy they just vote for who can win? Admit it your just going to vote for what your news source tells you to vote for? And disregard any policy or actual politics or of the party you vote for?

The arguments are so bitter because the stakes are so low.

That's the truth in American Translators Association politics. The bylaws say boardmembers have to be sacrificial altruists. Inevitably, the board fills with cretins who cannot tie a shoelace. Agency owners then hired outside failed corporation hagfish to install their (highly paid) exec to steer all board meetings so that agencies write the amendments and punish any who balk. The Chicago Translators Association does not allow Artificial Persons to join, so the National Trilbys fabricated a fake Midwest Association to replace them. But CHICATA, like genuine LPs, is still there since 1987.

So the impression I am getting here is that the Mises Caucus took control of the national party fair and square under the rules and their opponents in some state parties are throwing tantrums.

True dat; but the US is a federation of states; the states were not formed by the federal government defining individual borders, as states do with counties.

Isn't there some mantra about local being best, government-wise? About devolving power downwards instead of consolidating it upwards?

The national organization won power fair and square, but are now abusing it.

How, exactly, are they abusing their power? For all Doherty's pants soiling, the worst thing I can say about them is that they're playing by the same rules as their opponents. It wasn't the national party that conducted a purge of everyone who didn't agree with them or dissolve the party without a vote from the membership or ignored the existing rules.

As I said, it is top down instead of bottom up. Ken yee nae read?

If you think top down is just fine, then you also are fine with the feds telling states what to do, with the EU telling nations what to do, and with the UN telling everybody what to do. Or maybe you think that the Mises Caucus is special and deserves special top down authority and would never abuse it.

It isnt top down. The whole push by the MC has been a bottom up plan. To take on local affiliates to garner positions in the party.

The national party is telling state parties what they cannot and must do. That's top-down.

They really aren't. They are simply using their position at the top to change various statements like every leadership before them. They are literally just encouraging people to run locally still.

What demands are they forcing on affiliates outside of mission statements that are always a top level action?

No they are not.

A state party broke its own rules to pass changes that affect how that state party participates at the national level. It is perfectly appropriate for the national party to say, "Sorry that is not being done by the rules YOU setup, and therefore we won't recognize those changes".

I can read just fine. You just aren't making a whole lot of sense here. This isn't the Mises Caucus trying to tell the state chapters what to do. It's the Mises Caucus trying to make sure they don't get screwed over by these particular state organizations. Moreover, the LP isn't a state. The LP and the Mises Caucus don't have the ability to throw anyone in a cage if they don't like what they're doing.

It's the top national party telling the bottom state parties what to do and not do. How is that not top-down?

Be specific. What actions are you discussing here. What are they forcing on other affiliates. Actual examples will help your argument.

Your obsession with the "ideas" of top down and bottom up is irrelevant to libertarianism.

But if it were since the members of these state LPs did not get to vote on dissolution or disaffiliation and do not approve of what their state party officers are doing, you are factually incorrect about which side is top down and which side is bottom up.

That’s a great false dichotomy you’ve posited.

Or - from what it seems - they're trying to prevent the local party from abusing *its* power.

The local rule-change did protect incumbents after all.

Yeah, pretty much. The staff writers here seem bound and determined to contort themselves into pretzels trying to obfuscate the obvious.

It is an extension of what the NH LP did a few years ago where they tried extending all powers to a single individual to disallow the MC from gaining any say in their party.

The out-organized would rather lose with the "right" people (socially acceptable leftists who will never implement actual libertarian principles) than win with the wrong people.

" win with the wrong people. "

Just what can the wingnuts "win" in the context of the Libertarian Party, modern American politics (outside a few deplorable backwaters), or the modern American marketplace of ideas? The culture war has largely relegated stale, ugly, right-wing thinking to the irrelevant sidelines in America.

Youre a repetitive idiot without content. In other words, youre a so called “Democrat”.

Winning is using spoiler votes to repeal bad laws... what we did in 1972-72 when LP plank became Roe.

Looks to me like they are taking action, not throwing tantrums. Following the rules of secession "fair and square".

Cite?

Whether or not it was "fair and square" is largely irrelevant to the reality of their governance, which is best described as malicious incompetence. People of sound mind are disaffiliating, through their lapsed memberships and unrenewed contributions, from the reactionary alt-right clown show.

So you prefer a party of money and false principles over one of actual principles.

What makes them alt-right?

They aren’t praising Hillary enough or telling people to just bake the damn cake or pushing BLM talking points?

HEY! Then they do have commonality with the Republican party.

hasnt the overton shift made the R's a center left party?

Pretty much yes, essentially proving that they were just the left wing equivalent of neocons calling themselves libertarians because they don't like the baggage associated with the term that accurately describes them.

The NMLP leadership put in rules to prevent themselves from being replaced, but the Mises people are the ones who “seized control”

650 to 150.

Apparently there were only 150 liberaltarians who support UBI and hate speech codes in all of the US.

Or they could not get Soros to fund them.

Or they could not get Soros to fund them

I wouldnt state that too loud... you know thats exactly whats coming to an organization near you!

If he cared about the LP he would be doing it.

Or is that what the People for Liberty group is?

That pretty much sums it up. The LP establishment is grossly breaking the rules to avoid a takeover from the bottom up by a popular faction within the party.

And yet, I am sure that this is somehow all Trump's fault.

Not all. But partially.

Lol. Your TDS is amazing.

It's funny how over the years, any libertarian could refer to any US president as inadequate, incompetent, a tyrant, or a criminal, and other libertarians would have no problem with that. But if you refer to Trump that way, all of a sudden it's a "Syndrome."

I think the problem is that you ONLY refer to Trump that way, while ignoring the obvious machinations of h surveillance state to destroy him precisely because he, or rather his movement and supporters, threaten their existence.

And then reason does its presidential surveys where so many of its contributors produce their tortured rationalizations of why they will vote for Obama or Biden.

Yep. Austrians had to talk differently about Jews after the Anschluss there. But it was all done legal as sea salt, with over 90% of counted votes backing the single National Socialist party 13 Jan 1935. That's Austrian economics in practice!

I don't think Austrian economics is a theory of electoral procedures in representative governments, so your assertion if factually incorrect.

I suppose an Austrian political economist might right about how failed government programs impoverish a population and provide conditions where demagogues will demand scapegoats. I think Mises and Hayek may have written a book or two about that.

Pathetic cunt.

This has been fantastic to watch.

The Mises Caucus spent YEARS, going state by state, building support for their slate within the Libertarian Party. New Mexico did not want that to happen to them, so they called a flash Constitutional Convention, online, and without warning. This is tantemount to meeting in the dead of night while your political rivals sleep to pass legislation because you don't have the votes otherwise.

Why Doherty thinks this is anything but dirty politics is a bit bemusing to me. And it is in fact hilarious for him to parrot the talking points of the detractors, without at least acknowledging that all these procedural shenanigans are deliberate attempts to subvert popular votes.

I particularly loved the use of language to seed how he wanted people to think of the people/parties involved, it was straight out of the huffpo/mother jones playbook. You see left wing rags pull that crap all the time, instead of just reporting facts they will always mention anything bad even if its irrelevant to the story, ex: "alleged dog murderer and suspected wife-beater Steve O'Neil (R-MS) went to the grand opening of a local park with his wife today where he shook hands with noted philanthropist and lover of kittens Mike Seymore (D-VA)"

Bye, masked Trumpanzee infiltrator.

He does seem to have failed to cover that the dissolution vote was don sneakily and hat former LPVA chair Holly Ward is an employee of a rival group, People for Liberty.

the concept of grouping individual-minded people to accrue political power is something ... I don't know what yet but it's something

We have to take power to dismantle power.

That's the libertarian conundrum: How do you put people with no desire for power into positions of power?

There would exist an answer in your world if you had the ability to think outside of absolutes and strictly binary terms. Your low iq is kinda bothering me right now.

That’s why he’s best mocked and pitied.

It's not really a conundrum. A libertarian can run for elected office and just choose not to use 99% of the power the office gives them. You own guns but choose not to shoot people, that's basically the same choice you have if you were to be elected. You've got the capacity for a great deal of violence, it's your choice to use it or not.

Think of Ron Swanson in Parks & Rec. He views his government job as an opportunity to destroy the beast from within.

The difference is that in your example you exist in a world where nearly everyone else around you is using guns to shoot people (including your own people), and you're insisting on not using guns ever even if it means your own demise because muh ivory tower principles.

And hell if i want to be more accurate, its more akin to them refusing to even use pepper spray in the fight, when other people are running around shooting guns.

See "Libertarian Candidate Speech" https://bit.ly/3AunUfM

“Great mean do not seek power. They have power thrust upon them.”

- Lt. Cmdr Worf

Carry on, Klingon!!!

Wow, talk about fucked up. Mises Cocks want to nationalize a political party representing individualism.

It's broken and needs to burn down in order for something better to rise in its place.

Fucking Mises nationalizing racist fucks. The brand is now a taint.

Says the person who knows ignores the decades of work the MC has done to win state-by-state agreement - but a couple states don't like the direction they want to take the party and it's all 'ohh fascism!'

"decades of work"

The Mises PAC started in response to comments Nick Sarwark made only a few years ago. The real decades of work were put in by political activists, not takeover organizers. But do go on, I've got plenty more popcorn.

Nick was the literate grownup in the room. I expect we'll be welcoming him back in another couple of elections. Then again, maybe the Maeces are real libertarians pretending to be Trumpanzees to draw off spoiler votes and sink Televangelist National Socialism. False flags wave both ways...

National LP conventions do often have the flavor of a group of borderline autistic teen boys trying to get attention while they have a moment on stage.

At the convention where Nick Sarwark was elected chair, I ran into him (I knew him from when he was a law school student in DC) and observed that he, like all the other on the spectrum libertarians running for party offices, thought campaigning was just putting a flyer on every chair in the convention hall and then running back to your room to watch Star Trek reruns. Having spent a lot of time with Democrat Party fundraisers, I told him you had to ask for something to get it, and that all these peeps should actually ASK for a vote. Nick then immediately stuck out his hand to shake and asked me for my vote, and proceeded to be possibly the only person in the race who did that. So he was at least educable.

It’s already a national party?

Shhhhh, Truth is bad, stop trying to derail his rage train, you might actually force him to think instead of emotionally react!

Fuck off, cunt. I think more before 9AM than you have in your entire life.

Obviously. Everyone is persuaded of that now.

The actual members of the Virginia LP and its regional affiliates disagree with this sneakily taken vote.

"People's Front of Judea? We're the Judean People's Front!"

SPLITTERS!

What I see is the pro-racism, pro-censorship, pro-child mutilation forces within these states have decided if they can't continue to skin suit the LP then they want out. Good riddance to leftist garbage.

Not only do they want out; they want to burn the building down after exiting.

Just more evidence proving they were effectively progressives because if they can't force you to bend the knee, then they will go scorched earth.

Even if they aren't the Pro-Racism wing, they have traditionally been the Anti-Wrong People wing. So much so that they will agree all day with the Pro-Racism democrats in order to avoid being lumped in with Wrong People.

Bill Weld's "Just bake the damn cake" nonsense was incredibly bad for the Libertarian Party. It basically said, "The Libertarian Party agrees that you should not have the freedom to have, or act on wrong ideas."

That lost us an entire generation of libertarian kids. Why should they defend liberty, if the Libertarian Party isn't willing to defend liberty?

"That lost us an entire generation of libertarian kids. Why should they defend liberty, if the Libertarian Party isn't willing to defend liberty?" Huh? And these "libertarian kids," are they dumb or ignorant enough to believe that the LP is the only game in town?

Exactly.

I can't speak to anything about New Mexico, but a large portion of the content about Virginia is wrong or extremely misleading. For example, the SCC issued no such letter. Doherty is referring to a certification form that is automatically attached to the computer-processed output of the submission form. Submission and processing timestamps are the same. That same process resulted in the SCC contacting the director of the nonstock corporation, who immediately got back in touch and told them to halt the action. The forms are publicly available, and they prove that the chair violated they law. The most relevant part of the code is 13.1-902; the cabal claimed to dissolve under 13.1-903, which does not apply, then submitted under 13.1-902, which prohibits their actions. The only part of the information not publicly available is the motion/meeting minutes, because the bad actors have refused to release them (or the recording). Was there any research done on the law or publicly available forms themselves?

Sure there was research done. Doherty asked the people in the Virginia party what they thought the rules were and then printed it. That's research.

It’s become SOP at Reason.

We get what we pay for...

"It's become SOP at Huffington Post."

There i fixed it for you.

I am happy to have two LPs I can support. Gutless girl-bulliers, mystics and boothead communists are poor substitutskys.

Once again, just like when Trump took over the GOP, it wasn't conservatives who deserted. It was establishment tools who fled. So too, it seems, is happening to the LP. Good riddance to the go along crowd.

In a while, we'll have the Libertarian Party (US), the US Libertarian Party, the Association of State Libertarian Parties, the National Libertarian Party, etc. etc. and we'll end up here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WboggjN_G-4

Dissolve the party at all levels and reform it into a debate club.

Did this view of yours change just this year? I bet it has.

To clarify, the Virginia party still exists, unambiguously. The tagline on this article is just totally wrong; you could at least have the decency to pretend it's in question, rather than taking a stance that is incorrect. Every member of the party other than the small group of conspirators is still operating as usual (actually, much more actively than usual, because people are PISSED). The only thing in limbo is recovering some of the assets the conspirators destroyed or removed, which has already seen progress. I really hope Doherty issues some corrections at some point.

How will the party recover assets without invoking the apparatus of the State?

Libertarians are not opposed to using the state to correct cases of theft.

We're not anarchists.

We are anarchists. Anarchy means "without rulers". If we applied the NAP and prohibited government from initiating force there would be no rulers. Having no government would be "sine imperio".

Lord you are an idiot. You want to be an anarchist? Fine, just do not call yourself a libertarian, because you are not.

It's such an autistic view of libertarianism, as you said, they don't understand that libertarians aren't anarchists, we recognize that the state has certain functions that require a monopoly on violence.

Libertarianism is not the *complete* dissolution of the state.

" we recognize that the state has certain functions that require a monopoly on violence."

Nope. The state has certain necessary functions that require violence, but absolutely, categorically do NOT require a "monopoly" on it. The necessity of a minimal state doesn't imply that if a burglar breaks into your house you can't shoot them, for instance.

So you think an armed group of libertarians should confront the thieves directly?

If everyone respected the NAP, there'd be no crime and no need of government. If there was utopia, everyone would respect the NAP.

Opposing the existence of the state doesn't require that you to avoid using the state's apparatus to accomplish appropriate moral objectives when the state has made it illegal to accomplish appropriate moral objectives in any other way, such as with private police and private courts. Aiming to achieve a principled societal order does not require shooting yourself in the foot by pretending that order already exists.

Do . . . do you think libertarians are opposed to states?

Hope in one hand...

Narrator: He would not.

Not really surprised. In 2020 a career prosecutor lost the Republican primary for my county's District Attorney after campaigning on which candidate would do more to fight drugs and prosecute “quality of life” offenses. He then ran (and won) on the Libertarian Party line.

Given that the tenets of Libertarianism are at odds with hierarchical organization, I don't really see how it would be possible to organize and then maintain state parties, let-alone a national party.

Which tenet says there can be no organization? You can have a group of individuals working together.

You see this a lot with left libertarians and hardcore ancaps who want to smash hierarchies (much like the communist).

ALL anarchists have always been communo-fascist socialists and remain so today.

It has to work on the principle of single issues. You can get a lot of people to agree on ONE thing. In the LP's case it should be stopping government from initiating force.

The 1972 platform repealed bad laws. THAT is what works

Which tenets of libertarianism are at odds with hierarchical organization?

I don't really see how you could be so ignorant.

Can the formerly Libertarian but still "major" party in New Mexico give itself a different name? What should they call themselves? The "Classical Liberal" Party, or maybe the "Non-Aggression" Party? Or maybe, in a challenge to the so-called Mises Coalition's association with their claimed namesake, the "Human Action" Party?

The Forward Party like all the other cosplayers.

I <3 you

The Hayek Cabal?

Adopt the original LP platform and grow 12% per annum. And do not let infiltrators meddle with the planks. An long as commie anarchist isn't in the name, it'll work.

Call themselves the Rothbard Caucus to drive the MiCaucs nuts, since the LPMC has basically nothing to do with their namesake either, the classical liberal Ludwig von Mises. They're a bunch of Rothbardo-Hoppean anarcho-paleocons.

This is a shame - and it's quite disgusting that Virginia would rather throw its membership under the bus and try to disenfranchise them as part of a temper tantrum than plan a real strategy. Someone like Spike Cohen didn't just walk away from the party in a hissy fit, which is what Virginia's board is trying to do.

Here in Oregon, the Mises Caucus fixed the state party after it nearly fell apart due to sabotage by the GOP.

Exactly.

I miss Spike Pinhead and Robert Dear about the same.

If they weren't running any candidates due to wariness, lack of interest, and a loss of confidence in the brand, then it seems to me there wasn't much to save. In the LPVA, an act of disaffiliation necessitates dissolution.

Again LOL.

"The Human Action Party - Because everybody else is racist, fascist, or both."

Whoops, meant in reply to Dan S. above.

Its so sad to see the LP disintegrate, yet so utterly expected. The party was never pure. What was once a dedicated group of anti-duopoly pragmatists has become a partisan mob of self interested activists and secret big party operatives. We've always allowed a component of our party to embarrass us or become the national joke. Our message was overshadowed by jokers with boots on their heads. Because of us, the country was never able to take a 3rd party seriously, and may never again. The duopoly wins.

Our message was overshadowed by jokers with boots on their heads

or fatties stripping at a national convention

Do you think that was another attempt to ingratiate themselves with Democrats?

I mean now that so much of their culture and their advertising features worship of obese singers and models?

Both. We didn't have those infiltrators in 1972 and 1976.

Another looter brainwashee pretends to not understand spoiler vote clout

Some of us remember that in the 2020 election the 2 libertarian senate candidates shaved just enough votes from the 2 Republican candidates (they were leading) to prevent them from winning on the first ballot. Ended up giving the Democrats 2 senate seats and a split senate. Otherwise the Republicans would have been in the senate majority. Instead Kamala gets to settle tie votes and the Republicans have to kiss Manchin's and Sinema's posterior. Thanks a lot Libertarians

So you are saying this is all just a Republican plot to get rid of the LP?

The GOP incumbent in one PA Congressional race is conspiring with Marc Elias's team of Democrat lawyers to keep Caroline Avery, the LP candidate, off the ballot.

And reason hasn't done any coverage of that.

You cowardly prohibitionist girl-bullying looters are welcome as hail.

So you're saying we should outlaw all except for one party to prevent this sort of thing happening again.

Voting 'to keep the other guy from winning' is how we got Biden.

In other words, the party is still nothing but a big clown show. Long live little-L libertarianism!

Except one group of clowns wants to accept and even support you for being little-L libertarians, even you're racist, as long as you aren't violent. The other group of clowns rejects the first and you for reasons stated in the first sentence.

We've drained billions off Kleptocracy efforts to enslave cretins. And we're still here.

Who’d a thunk it? … Amongst the fiercely individualistic thinkers, tribalism has reared its beastly head!

I am proud to be a little-L.

A libertarian political party is a contradiction in terms. I'm a libertarian, and for me joining a political party would be like a Christian joining a satanist church.

Another anarchist false flagger infiltrates the commentariat.

Having checked the website of the Mises Institute and the Austrian I find no such lamentations regarding the situation within the Libertarian Party. However as much as there may be differences the Mises caucus has scored a great victory in at least attempting to steer the party in the correct direction of non interventionism, sound money, liberty and less government.

Of course this rankles the liberal progressives who want more heavy handed government to guide us through our lives( we don't know what's best for ourselves, you know) then there's the woke/CRT /LGBTQXYZ indoctrination the progressives want to force upon every one. Along with that the progressive idea of foreign interventionism in the form of military interventionism if necessary, which in the past 150 years it seemed , to be necessary according to their dogma.

What ever it is that seems to cause so much anxiety with those who seem to equate the Libertarian party with neo-nazi/KKK/Proud Boys is beyond me. However there are those who apparently despise the ideas of personal liberty and responsibility along with less government, less taxes and less interventionist policies. It seems they have problems with the ideas of sound money, the elimination of the Federal Reserve and IRS as well as a host of other needless government agencies whose only success is to spend trillions and achieve very little if anything.

Just think about what is happening in public education, how badly it is failing and how it has become more brainwashing and indoctrination instead of teaching real skills and learning to become real contributors to society instead of pretending to be victims of oppressors.

Liberals have very little use for liberty and freedom. They want total control over everyone, Post modernist neo-Bolshvism and neo- Marxist instruction at nearly every university has instilled the idea of turning America into the new Soviet Union.

Is this what you really want?

Exactly.

The Mises Institute is a 501c3 and not related to the Mises Caucus, as I understand it.

-What ever happened to the Popular Front, Reg?

-He’s over there.

—SPLITTER!!!!!!

I'm loving all the people in the comments who were all about the official Libertarian Party until some people took over the party that said mean nasty things, and now they're all pretending that they're anarchists...

If the LP goes away entirely, it will be a big win for libertarianism.

So: good riddance.

The word Libertarian needs to be left in the dust by people running a political party imo. If Gary Johnson, the best candidate the LP could have put forward, could not make major inroads running against super unpopular major party candidates, what is the point of running even shittier, name candidates that are even easier to ignore.

There needs to be a big tent pragmatic, socially liberal, fiscally conservative localist party that targets moderate independents with creative policies and least-harm taxation.

The LP is for people who want to be right and virtue signal their principles instead of actually pushing society towards liberty. Most people have a complex array of values, and forcing all policy through the lens of one singular value is never going to win the race. Besides, I strongly disagree extremist libertarianism maximizes rights.

The LP has repealed bad laws with spoiler votes for 50 years. Whining sockpuppets pretend not to know that, per script.

State Libertarian parties should be allowed to leave, but upon leaving should change their name to something else. I'm all about having lots of third parties, but also realize that a party that holds 70% of my view is much better than the Republican and Democrat parties that holds less that 30% of my views.

While I may disagree with some of the positions of the Mises Caucus, I also know that the previous leadership was incompetent and left the party wandering in the wilderness. It was time for a change of approach otherwise there wasn't much of a point. I'm willing to give the Mises Caucus a chance to see what they can do.

If the LP starts to gain power and retains 70% of the positions that I hold then in my mind it is a win. No power with 100% of the positions is a loss because nothing changes. We can't isolate ourselves in a pretend world. We must live in reality and that means there has to be some compromise.

As a libertarian, I don't expect other people to completely agree with my positions even if I feel that I'm 100% correct. People should be allowed to have their own opinions.

I feel that the state party battles are personal battles because of egos. Face it the Mises Caucus took control of the party because if the deficiencies of the previous leadership.

Taking your ball home because you are pouting does nothing in the big picture. If you want to make change then remain in the Libertarian party and persuade. The Libertarian party needs to grow and win elections and power. Your plan is to diminish power and relegate the Libertarian party to the dust bin of history.

Do some self-reflection and reconsider if your actions promote the goal or simply makes your ego feel better.

Exactly so.

I find it odd that some commenters are saying the LP is irrelevant. Yeah, right. Iin this time when government surveillance is pervasive and intrusive. When your very online activities are being secretly recorded. When we have secret jails, secret tribunals and secret police. When your car is being tracked by license plate readers, when your credit card purchases are being tracked by the government, when the main stream media offers up nothing but propaganda and outright lies. When thousands are being held without bail for over a year, some of them being beaten and tortured in Washington, D.C. jails. When your phone conversations are being recorded, when you can be arrested and charged with treason and or have your phone taken from you by the FBI without a warrant, when your rights are being whittled away bit by bit under your noses. When public schools are being used to brainwash and indoctrinate children.

You have no need for the Libertarian Party when both of the two main political parties care less about your freedom and liberty, pass more laws that are meant to undermine the very foundations of what America used to be, now replaced by every form of spying and intelligence data gathering that even Orwell could not imagine.

You have no privacy, no liberty when the government seeks new ways of spying on you. Your currency is being inflated and you are buried in debt. Price inflation is forcing people into second and even third jobs just to make ends meet.

Bit by bit, slowly and without hesitation, the state is making itself all powerful and all encompassing into our personal lives. It is doing so with the approval of the people in the name of security and safety.

All true.

"The LP is irrelevant" because they don't win elections, and don't make a serious case as a big tent party that can pull votes from the Left and Right in equal measure to actually move the country in a libertarian direction.

It's one thing when they were actually trying to expand the party, for instance with Gary Johnson - but they generally put forth unserious candidates and the radical wing is more concerned with virtue signaling their purity than victory. 2020 was the first time I didn't vote LP, and from the direction it's going, it's looking unlikely in 2024 too.

The Libertarian Party is detrimental to libertarianism when they embrace the reactionary radical paleolibertarianism of Mises and Rothbard. Calling for legalizing child labor, repealing the Civil Rights Act and playing to a crowd of alt-right edgelords is the WRONG DIRECTION.

The LP is irrelevant because you cannot impose libertarianism politically; people need to want libertarianism first.

Zora Neale Hurston, the libertarian novelist and anthropologist who was an early victim of cancel culture because of her opposition to FDR, the New Deal, and our entry into WWII said "No man may make another free."

As opposed to the neo-libertarianism that you subscribe to, which is largely indistinguishable from progressivism.

The LP has elected a couple of hundred local officials, and of course had one Congressman elected in another party switch to LP to serve out his term.

Legalizing child labor is crucial for education as the government schools continue to collapse. People under 16 need to be able to apprentice to learn skills.

Maeces and Rotbutt are anarchism, communism, nothing to do with the LP except sabotage and hatemongering.

Democrat media are very excited about this story.

They fail to actually cover and investigate, for example by reporting that this vote was taken in secret by a state central committee with many deliberately kept empty vacancies so that the voting seems rigged.

The actual LP of VA - its members and regional affiliates - say they are simply repopulating the state central committee without these people.

Holly Ward works for a group, People for Liberty, that is a fundraising rival to the LP and could seek to supplant it by creating affiliates that become state political parties; no one seems to mention that in the coverage. Even if she is sincere in her beliefs this conflict of interest should be mentioned, no?

People for Liberty is run by Dan Fishman, who was executive director of the Libertarian Party nationally for one term, but was not kept on and re-hired. Before this May's national LP convention Dan Fishman was making extreme charges about the Mises Caucus as a whole based on his opinions about particular individuals in e.g. the Libertarian Party of New Hampshire.

The various charges of bigotry are ludicrous. Gay people continue to be well represented in the LP, like Bruce Majors, the chair of the DC LP, or Dan Ford, the chair of the Libertarian Party of Loudoun County and a Mises Caucus member. The edge lordy tweets from the Libertarian Party of New Hampshire, celebrating the death of John McCain and other items in bad taste, are reportedly the work of a Jewish Libertarian, Jeremy Kaufman, so the idea that it represents anti-semitism might require some actual evidence.

Holly Ward et al are people upset that they lost at the May national convention 650-150 to delegates that did not want Libertarians to try to appease or ingratiate themselves with "woke" media and Democrat think tanks, as so many Beltway liberaltarians do. The delegates removed an extreme pro-abortion plank so that individual candidates could take any position on the spectrum regarding abortion, without being in conflict with the platform. They changed a plank denouncing bigotry to make it clear that they do not think it is the government's business to define bigotry and label people bigots, police speech or people so defined, or impose additional punishment on criminal acts because they are labelled by the government as bigotry.

Another thing not mentioned much in the coverage of this hissy fit by the LPVA officers is that the GOP and Democrats do this stuff often, changing the locks on offices when one faction takes control, or seizing assets and deciding how they will be spent, as Donna Brazille detailed in her book on her time at the DNC and how Hillary Clinton's faction seized control of funds raised. In that light this level of infighting may simply indicate that the party is now valuable enough to fight over

Bruce Majors,

Chairman,

Libertarian Party of the District of Columbia

Any time someone deliberately and repeatedly uses the incorrect form of "Democratic", such as "Democrat Party" or "Democrat think tanks", I immediately know their comment is not worth wasting my time.

Don't tread on New Mexico, assholes! Chingada a tu madre, and fuck Robert's Rules of Order!

Libertarians are secretly plotting to take over the world an leave you alone...

Yep, the national party has no legs to stand on with respect to the party name. "Prior art," case dismissed.

If the Libertarian party can't organize and govern itself, how could it possibly be expected to govern a country, state, county, or city?

Libertarians bring up some very good points, and they have some very good ideas (hence, I subscribe to Reason); however, they are in no way ready to govern.

You are so mired in a progressive mindset that you don't even understand how dumb that question is.

Let me spell it out for you: libertarians don't want to govern; libertarians want people to live free, make their own choices, and accept the consequences of their own decisions.

If libertarians shouldn't be in favor of any kind of governance, then the party probably shouldn't exist.

A Libertarian Party could exist in the sense that it can pursue possibly non-libertarian policies that lay the groundwork for a libertarian society. For example, firing public school teachers who teach CRT would be a non-libertarian policy that would advance libertarianism. Another example would be balancing the budget.

However, in the US, such policies are best pursued in the Republican party at this point.

Could they do worse than the current regime?

We do not seek to govern. We use spoiler votes to repeal bad laws. See "The Case For Voting Libertarian" (complete with audio and charts since 2007)

A non-Mises Caucus member of the LP of VA central committee shared this opinion with me:

"I've done a thorough examination of the law and documentation related to this stuff, consulted with multiple lawyers, and Holly is undeniably guilty of a class 1 misdemeanor as of Tuesday morning. Like, no wiggle room kind of guilty. Which is...insane to me. How could she be so foolish to put herself in that situation? Of course it's unlikely any prosecutor will care, but even so, it might have some relevance if there is civil action."

This exact same thing occurred in 1982. An Army of God Prohibitionist whack job infiltrated a state LP, began flinging ordure at individual rights and demanding men with guns threaten other doctors and enslave females. The Pennsylvania LP cut the infiltrator adrift the way you would a hulk packed with ebola vectors.(bit.ly/3BMjKAb) Now Trumpanzees get even with our causing their Orange Lewser to fail twice in the popular vote. The Henchman-Boothead-Anarchocommie crowd before were simply the Dems getting even for our 4 million votes shattering Shrillary. My donations are going to the NM libertarians, not anarco-fascists.

Where can I send in my $3 for an English translation of this comment?

McArdle and Harlos are both paralegals from other states, so obviously you can trust their expert legal intuitions and unbiased interpretations of the laws of Virginia.

The Virginia code, as well as its interpreting judicial decisions, are written in english, not sanskrit

Goodbye and good riddance! Too often the Libertarian Party has made use of star power to attract good, thoughtful, well-meaning people only for it to degenerate into a tool of the left who's candidates can be used to swing elections for the Democrats. If the LP was serious then their central focus would be changing the voting method to make it easier for their candidates to get elected. Otherwise, the LP is a waste of time and money.

A desire for star power isn't what these affiliates are clinging to. While there were many things that needed to change about the pre-takeover party, the central issue is the way the clique in power, a faction more interested in trolling leftists and allying with fringe right-wing populists than in strengthening a right-left libertarian coalition and professionalizing the party, has used the national party to interfere with "rogue" affiliates, state parties not controlled by the Caucus, which is exactly what they rightly accused the pre-takeover party of doing. The LNC is not a central court authorized to insert itself into state party affairs and give a final interpretation of the bylaws of all affiliates for the sake of state party *cough*Mises Caucus*cough* members. Membership at the state level is separate from national party membership. State affiliates came first and have the right to exit (secede, if you will) from the compact on their own terms, an arrangement one would hope the pro-decentralist Mises Caucus could respect and appreciate, but evidently not when they own and operate the national party. Just like they're opposed on principle to intellectual property monopolies, but not when they want to "protect" LP branding by threatening legal action against any disaffiliated group who would dare potentially infringe on National's registered word mark.

The old guard essentially advocated for being the new version of an ineffective GOP who only played a controlled opposition party to the DNC. Bake the cake, anti racism, no effective policies. No actual protection at all. They would rather sit and bitch about things than actually affect change or protect liberty.

Many LP candidates get more votes per dollar spent than their Democrat or Republican rivals, who often spend $25 million and up to get 5 million votes in a statewide race. LP candidate rarely spend $1 per vote.

So by that measure the Democrats and Republicans are the joke.

It's just that they are a joke at your expense, funded by corporations and government sector unions.

Having blamed everything bad that has ever happened to him on others he has adopted a persona of powerlessness. So instead he will just bitch about everything while declaring himself a victim.

A lactose-intolerant self-licking ice cream cone

Well, that . . . and disaffected, inconsequential, on-the-spectrum, frequently bigoted, always antisocial, right-wing culture war casualties.

Carry on, clingers. But only so far and so long as better Americans -- the liberal-libertarian mainstream, victors in the culture war -- permit.

And the homoerotic fantasies.

Arty likely has recorded Trump’s speeches and pounds himself in the ass with a dildo while watching them. Fantasizing that Trump is wrecking his rectum.

He’s just an angry broken drunk, who channels his impotent drunken rage at Trump and anyone who dares agree with Trump on anything. He would probably rather have WW3 out of pure spite than see Trump return to the White House.

His fixation seems more oral.

I am creating eighty North American nation greenbacks per-hr. to finish some web services from home. I actually have not ever thought adore it would even realisable but (caf-07) my friend mate got $27k solely in four weeks simply doing this best assignment and conjointly she convinced Maine to avail. Look further details going this web-page.

.

-------------------->>> https://cashprofit99.netlify.app/

Libertarians are revolting!

You must have access to some seriously good pot because you're clearly high right now.

I'm honestly starting to wonder if they are more concerned with just having their own little special snowflake club where they can constantly jerk each other off about how much more rational and intelligent than all those "unprincipled" peasants than actually moving the needle on liberty.

Michael Malice said it perfectly, in one of his interviews, "They say they prefer sushi, but they'll eat steak every time".

Uh hilk, uh hilk... how original! No-content DEA sockpuppet HRIMNIR's appeal to Harry Anslinger and plant-leaf Assassins of Youth and Avatars of Satan. Jidja run out of international stock-exchange Jewry bait? Still mainlining ethanol?

Back in the 90's I ran for state Rep as "filler" candidate for the LP. I got several hundred votes with no expenditure at all.

Wow, I was infinitely more effective than either major party!