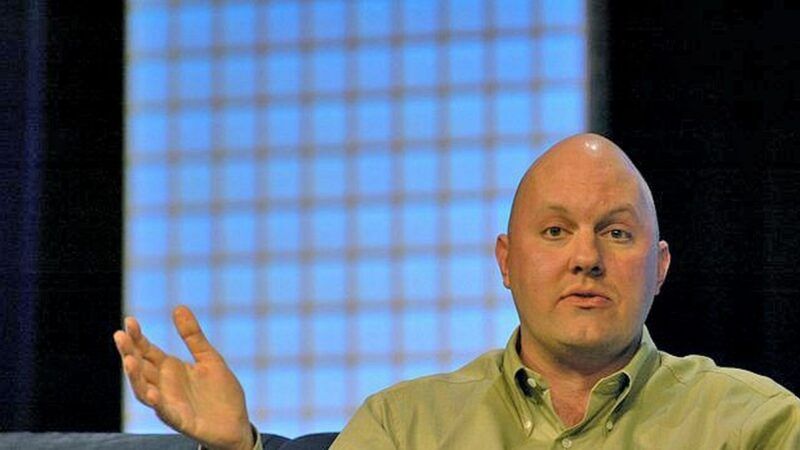

Marc Andreessen's High-Tech Fix for the Housing Crisis Lets Him Keep Being a NIMBY

The venture capitalist's $350 million investment in WeWork founder Adam Neumann's new venture Flow is supposed to help renters build community and equity. They'd be better off if we just built housing instead.

Marc Andreessen can't seem to decide whether he wants to fix America's housing crisis, make it worse, or creatively reinvent an untenable status quo.

On Monday, the billionaire venture capitalist announced that his firm, Andreessen Horowitz, would be a major investor in controversial WeWork founder Adam Neumann's new housing venture Flow. The New York Times reports that Andreessen's firm will plow $350 million into the new company and its as-of-yet unrevealed business model and that Andreessen will sit on its board.

In a blog post, Andreessen said that Neumann—who was ousted from WeWork in 2019 after a disastrous initial public offering—had the brains and vision to remake a residential real estate market characterized by overly expensive owner-occupied housing on the one hand and "soulless" rental options that build neither financial equity nor personal connections on the other.

"In a world where limited access to home ownership continues to be a driving force behind inequality and anxiety, giving renters a sense of security, community, and genuine ownership has transformative power for our society," writes Andreessen. "When you care for people at their home and provide them with a sense of physical and financial security, you empower them to do more and build things."

These are awkward words to hear from the billionaire investor who's taken a drubbing in the press recently for his own part in limiting access to homeownership and stopping people from building things.

Earlier this month, The Atlantic's Jerusalem Demsas spotlighted a June public comment submitted by Andreessen and his wife, Laura Arrillaga-Andreessen, to the planning department of Atherton, California, opposing a plan that would allow multifamily housing in the ultra-expensive San Francisco suburb where he lives.

Allowing new apartments, the two wrote, "will MASSIVELY decrease our home values, the quality of life of ourselves and our neighbors and IMMENSELY increase the noise pollution and traffic." The vast majority of the Andreessens' neighbors who filed public comments likewise opposed zoning for new multifamily housing in Atherton, and the plan was dropped by the city.

As Demsas notes, this kind of NIMBY (not in my backyard) opposition to new housing, and the restrictive regulations it births, is a primary cause of America's housing shortage, estimated at somewhere between 4 million and 20 million missing units.

Andreessen isn't unaware of the country's housing shortage, or all the problems of immobility, unaffordability, and instability it creates.

His blog post from Monday notes that the unattainability of homes near prime job centers is a product of cities not building enough housing. And Andreessen's famous April 2020 essay "It's Time to Build" also called out American cities' failure to construct enough housing as yet more evidence of our hopeless national stagnation.

"We can't build nearly enough housing in our cities with surging economic potential—which results in crazily skyrocketing housing prices in places like San Francisco, making it nearly impossible for regular people to move in and take the jobs of the future," he wrote then. "The problem is inertia. We need to want these things more than we want to prevent these things. The problem is regulatory capture. We need to want new companies to build these things, even if incumbents don't like it."

One might be tempted to see his investment in Flow as redemptive—a $350 million investment to fix a housing crisis clearly counteracts any damage his NIMBYism has done. Yet, from the limited details available, Flow won't try to tackle the problems of overregulation and undersupply that Andreessen has correctly identified as the root of our housing woes.

The Wall Street Journal reported last year that companies linked to Neumann have been buying up thousands of existing apartments in fast-growing cities like Nashville, Atlanta, and Miami. The New York Times describes Flow's business model as basically a property management company offering "a branded product with consistent service and community features."

Rather than build new housing, Andreessen describes Flow as a new way of managing existing units that combines a "community-driven, experience-centric service with the latest technology" to solve renting remote workers' loneliness and inability to build equity and community in a home they own.

There's a strong whiff of standard NIMBYism in this idea. The alleged failure of rented apartment units to foster community and good morals has long provided the spiritual case for banning their construction. Encouraging people to build wealth primarily through homeownership has also sometimes given incumbent homeowners (including the Andreessens, apparently) a financial incentive to oppose new construction in their neighborhoods.

This isn't to say that remote workers' loneliness isn't a problem, or that lots of people are renting only because they can't afford to buy a house. But both those problems are downstream of our failure to build.

The superstar cities that took the biggest population hits during the pandemic also happened to be the places that have been building the least. If New York or San Francisco had managed to add new housing anywhere close to the rate at which they were adding new jobs, perhaps fewer people would have left behind their offices and professional communities for a lonelier but cheaper lifestyle of Sunbelt remote work. Massive home price increases in metros that have grown substantially post-COVID are proof we need to be building there too.

The same regulations that drive up construction costs and housing prices work against the community that Flow is trying to foster.

The first victims of restrictive zoning regulations were boarding homes and single-room occupancy hotels, places where people shared kitchens and common rooms, with meals frequently provided by their hosts. Laws still ban dorm-like housing in much of America today. If the idea behind Flow is to create more congregate living arrangements, a good first step would be to legalize those arrangements.

Eliminating density restrictions on housing would mean that developers wouldn't have to choose between adding more apartments and adding more communal space and amenities in a new building. That could also foster the kinds of social connection Flow is aiming to create.

There's obviously plenty of room for different approaches to the management and financing of apartments. Andreessen has a long history of backing successful Silicon Valley breakout companies. Maybe Flow will be one of them.

But even if successful, Flow will only be working on the margins. The housing supply crisis in America isn't primarily a problem of technology or stagnant business practices. Rather, it's a pretty straightforward product of government regulations that prevent new home construction.

Solving it is going to require building much more housing, not just a sense of community with your landlord. In addition to writing checks to Neumann, Andreessen could also choose to write fewer letters to his local planning department.

Rent Free is a weekly newsletter from Christian Britschgi on urbanism and the fight for less regulation, more housing, more property rights, and more freedom in America's cities.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

You didn't ask why someone was wanting to build multifamily housing in an expensive suburb?

That really doesn't sound like a developer wanted that but a city that was forcing a developer to do it for DEI points in exchange for allowing access to other projects.

Sounds to me like 'multifamily housing' is a euphemism for 'affordable housing' which is a euphemism for 'long term welfare recipients'.

Does that come with a dog whistle?

It's dog whistles all the way down.

I just worked part-time from my apartment for 5 weeks, but I made $30,030. I lost my former business and was soon worn out. Thank goodness, I found this employment online and I was able to start working from home right away. (res-15) This top career is achievable by everyone, and it will improve their online revenue by:.

.

After reading this article:>>> https://googleservice045.netlify.app/

No, they usually come with police sirens.

Yeah, this sounds about right to me. Maybe I'm wrong, but I highly doubt that the locus of San Francisco's housing shortage is due to a lack of housing options in Atherton. The need for new housing for Silicon Valley tech workers and affordable housing for the poor isn't because, goshdarnit, there just aren't enough rentals available in tony suburbs. I have no problem with living in a mixed income community. Of course, in my town, its an organic phenomenon. Jamming a bunch of poor people into an expensive community only winds up destroying the community.

I am creating eighty North American nation greenbacks per-hr. to finish some web services from home. I actually have not ever thought adore it would even realisable but my friend mate got $27k solely in four weeks simply doing this best (lao-07) assignment and conjointly she convinced Maine to avail. Look further details going this web-page.

.

---------->>> https://googlechoice.netlify.app

"The housing supply crisis in America isn't primarily a problem of technology or stagnant business practices. Rather, it's a pretty straightforward product of government regulations that prevent new home construction."

IOW, not in MY back yard, thank you.

YOUR back yard, however, is going to be the locus of "community-driven, experience-centric service with the latest technology" to solve renting remote workers' loneliness and inability to build equity and community in a home they own."

I am creating eighty North American nation greenbacks per-hr. to finish some web services from home. I actually have not ever thought adore it would even realisable but my friend mate got $25k solely in four weeks simply doing this best assignment and conjointly she convinced Maine to avail. Look further details going this link... http://oldprofits.blogspot.com

"The housing supply crisis in America..."

There is no such thing.

If New York or San Francisco had managed to add new housing anywhere close to the rate at which they were adding new jobs, perhaps fewer people would have left behind their offices and professional communities for a lonelier but cheaper lifestyle of Sunbelt remote work.

With all due respect, Mr. Britschgi, escaping this is the sort of cosmopolitan circle-jerk presumption might have been an even bigger reason for the abandonment of the metropolises. If the entirety of your social life consists of the people you know from the office, you're already living a pretty lonely and barren life. As someone who's made the transition from Manhattan to remote Sunbelt work, I can tell you, you find a lot more community here than there.

Those sound like code words and dog whistles.

Racist!

"If New York or San Francisco had managed to add new housing anywhere close to the rate at which they were adding new jobs, perhaps fewer people would have left behind their offices and professional communities for a lonelier but cheaper lifestyle of Sunbelt remote work...."

Neither New York nor San Francisco should do anything about adding housing other than allow the market to show what quantity is optimal.

All progressives should be forced to house 1 homeless person for every 500 Sq ft of space they have

A better plan would be to relocate all progressives outside America permanently. Or deposit the ones who stay into landfills. Then kick the illegals out. At some point in the comp,etion process we should end up with more than enough housing.

The problem is a coalition of the wealthy like Andreesen and the "activists for the poor". I see it building up here in Florida. The socialists are everywhere trying to hijack the high cost of housing as a wedge issue.

In our case, we have a couple of million immigrants to the state in a short time and a few lot of foreign investment to go with it, along with whatever these corporate investors are.

But whatever the cause, the coalition of rich and poor conspires to stop the construction of new housing. They get the activists focused on opposing anything that doesn't build new "affordable housing". So when a developer wants to put in a huge new luxury condo high rise, they oppose it. And the rich guys all smile, because that brand new, bigger and nicer building would have made their older, smaller and less attractive condo worth less.

And the activists fail to see that if you want anything other than tenement housing to be "affordable", you have to let builders oversaturate the high end of the market, driving prices down. Do that enough, and the lower middle class gets to move into mid-range housing and the low end gets freed up for the poor.... and the stuff that is falling down doesn't get propped up by rent subsidies, it gets torn down and a new high end property gets developed.

Nobody who owns a home wants this to happen. And nobody who gets money or power by being an advocate for low income housing wants this.

The coalition favoring this is progressive urban planners and libertarians which is why this issue is constantly popping up in Reason. I'd like to see the author(s) favor his neighborhood going multi-family before I take him seriously.

Do not engage Joe Asshole; simply reply with insults.

Not a one of his posts is worth refuting; like turd he lies and never does anything other than lie. If something in one of Joe Asshole’s posts is not a lie, it is there by mistake. Joe Asshole lies; it's what he does.

Joe Asshole is a psychopathic liar; he is too stupid to recognize the fact, but everybody knows it. You might just as well attempt to reason with or correct a random handful of mud as engage Joe Asshole.

Do not engage Joe Asshole; simply reply with insults; Joe Asshole deserves nothing other.

Eat shit and die, Asshole.

"When you care for people at their home and provide them with a sense of physical and financial security, you empower them to do more and build things."

No! No! No!

When people care for their own financial security, they go on to do more and build things; like their own home.

Oh, you aren't getting the big picture. You see, all you plebes should be living in rental properties separate from you masters. It will be great for you though, you will after all, "own nothing and be happy".

To bring this happy scenario to fruition sooner, Black Rock owned companies will start buying up single family homes as rentals. Eventually all plebes will be in rentals your masters own and be happy.

Isn't that great!

I have never heard a convincing theory for how Blackrock acquiring all the houses is supposed to end in profit.

I understand a REIT that has craptons of money that they *have* to invest in real estate... but private money should be cognizant of housing bubbles.

I have a friend who moved into a REIT owned house. Takes MONTHS to get basic maintenance taken care of.

He's really annoyed he made that decision, but the location works for him for right now so it's not a total loss. But his problem made me think about these companies.

Property management is hard. It's a pain in the ass, actually. Some companies are good at it, but an apartment building is a lot easier to deal with in many ways than a single family home, and many of the problems (roofing, exteriors, landscaping, etc.) are amortize over tens of hundreds of residents. And it's all in one place, not scattered all over the city.

I really wonder if these big single family portfolios aren't going to be an albatross around the REITs' necks. At least until the management issues are sorted out.

I am amazed that someone is investing with the WeWork guy again, and it's basically the exact same pitch as WeWork but shifted to housing instead of office space.

Like, that is amazing.

it costs about $400,000 (soft costs + hard costs) to build an apartment unit in many urban areas (more on the coasts, less in other areas)

$350 million will buy you about 875 apartment units

pissing on a forest fire

> "In a world where limited access to home ownership continues to be a driving force behind inequality and anxiety, giving renters a sense of security, community, and genuine ownership has transformative power for our society," writes Andreessen. "When you care for people at their home and provide them with a sense of physical and financial security, you empower them to do more and build things."

So, this sounds like condo conversions. Buy apartment buildings, put in some extra noise insulation, spruce up the common areas, flooring, and fixtures, run plumbing and electrical for internal appliances, then file a bunch of paperwork with the city. Which is a fine business to be in, if not the most exciting. Though WeWork somehow made executive offices exciting, so I guess you never know.

The only alternative I can think of would be condo conversions that were somehow a rent-to-own arrangement. Give tenants a 5 year option to buy their unit for, say, $360,000. Charge an extra $600/month with the rent bill that you escrow. At the end of 5 years, the $36,000 you escrowed is 10% of the option price, which ought to be enough for a down payment. The neat part is: if you have to evict the tenants, you can take the escrowed funds to take care of damage and owed rent. The not so neat part is: if real estate prices go down, people won't execute their option, so you are stuck with all the downside, but none of the upside.

Do they have meetings at Andreesen Horowitz where someone says “You know guys, I don’t think we have enough snake oil in our portfolio. What’s that douchebag Adam Neumann doing lately?"

-jcr

Sounds like these guys are waiting for the low hanging fruit (developers close to bankruptcy or wanting to cash out) to materialize and then pick completed units for pennies on the dollar.