How a Massachusetts Power Plant Illustrates America's Fraught Shift to Green Energy

Brayton Point was a coal-fired plant that tried to clean up its act. Protesters and politicians demanded its closure. A new offshore wind project won't be sufficient to replace it.

Under a hot July sun, President Joe Biden gazed out over the former home of one of America's largest coal-burning power plants to declare a new "frontier" in the fight against climate change.

Actually, it's just the latest twist in federal policy regarding how Americans get their electricity. One that promises to protect the environment, but might risk the resilience of the electric grid in the process by prioritizing supposedly game-changing public investments in projects like the offshore wind turbines being installed near Martha's Vineyard over incremental environmental improvements in more reliable sources of power.

That's a story that matters, in part because of the $370 billion in new climate spending that Congress is set to approve as part of the Inflation Reduction Act. Much of that new spending will take the form of subsidies and tax breaks for green energy technology. Those subsidies are meant to hasten the transition of America's energy supplies away from dirtier forms of production like coal and oil, including a new 30 percent tax break for offshore wind projects like the one near Martha's Vineyard that Biden touted as a replacement for the Brayton Point power plant.

But it's also a story that can be told without even having to step outside the footprint of the old Brayton Point power plant in Somerset, Massachusetts, where Biden spoke on July 20.

Though he stopped short of doing as some environmental activists want—to have "climate change" declared an official national emergency, which would unlock a range of executive powers that could be brought to bear against carbon-emitting industries—Biden's speech accompanied a series of executive orders aimed at mitigating the consequences of a warming climate.

"As president, I have a responsibility to act with urgency and resolve when our nation faces clear and present danger," Biden said late last month during his visit to Somerset. With his podium framed by a tangle of power lines and a neatly organized row of bright yellow construction trucks, Biden declared climate change to be "literally, not figuratively, a clear and present danger" to "the health of our citizens and our communities."

For the White House, Brayton Point is both a figurative and literal symbol of America's transition toward cleaner energy. On the site of the now-demolished power plant, a new manufacturing facility will assemble the high-tech, heavy-duty undersea cables necessary to connect offshore wind farms to the existing power grid. At the nearby harbor where deliveries of coal used to arrive from as far away as Colombia to feed the appetite of Brayton Point's three generators, barges will be loaded with the massive components needed to construct offshore wind turbines. Once those wind turbines are up and running, the power they generate will hook into the power grid via the substation that formerly delivered electricity from the coal-burning plant.

But they'll only provide about one-third as much power as the old, dirty plant did. The closure of Brayton Point (which was the result, in part, of sustained opposition by environmentalists) has coincided with other power plants in New England having to burn record levels of oil to keep up with demand. And Biden's announcement at the site of the former plan last week included items like new federal funds to pay for air conditioning in homes that lack it—a welcome gift to anyone sweltering through a summer heat wave, but also a move that will only put more pressure on the electrical grid.

The market for electricity is exactly that: a market. It has both a supply side and a demand side. An energy policy that closes off reliable supplies while demand continues to grow is a recipe for problems—and this won't be the first time that Brayton Point has served as a microcosm for the tradeoffs that sit at the heart of America's energy and environmental goals.

The Rise and Fall of Brayton Point's Cooling Towers

The first of four generating stations at Brayton Point was switched on in 1963 and by the end of the decade, the plant was one of the most powerful in New England. When running at full capacity, it consumed around 40,000 tons of coal every three days. Burning coal turned water into steam, which spun the plant's massive turbines to create up to 1,500 megawatts of electricity—enough to power more than 1.5 million homes and businesses across southern Massachusetts and eastern Rhode Island.

Unfortunately, the plant also belched a lot of hot water into the adjacent Taunton River and Mt. Hope Bay, from which the plant drew roughly 1 billion gallons per day to cool its power-generating system. That water cooled the plant, but in return, the surrounding aquatic environment got cooked. A multi-year investigation by the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Management in the 1990s blamed Brayton Point for an 87 percent decline in Mt. Hope Bay's fish population.

When Brayton Point's owner, the New England Power Company, applied to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1998 for a renewal of the plant's permit, it kicked off a decadelong effort to impose some environmental improvements. If Brayton Point was going to get the EPA's permission to keep operating, it would have to dramatically curtail the amount of water it extracted from the nearby river and bay—so much so that the plant needed an entirely new way to cool itself.

Enter the cooling towers. Though more commonly associated with nuclear power plants, giant towers that allow steam to condensate into water and be recycled into the plant can effectively cool other types of power-generating systems too. Facing the restrictions imposed by the EPA—and after a lengthy court battle over those restrictions—Brayton Point's new owner, Dominion Power, set about building a pair of 500-foot cooling towers. They were only the most obvious parts of a $500 million overhaul of the plant's cooling system to protect the river and bay.

"This agreement is a testament to the hard work and dedication of many individuals and organizations, who collectively can take much pride today for helping protect this valuable resource," Robert Varney, regional administrator of the EPA's New England office, said in a December 2007 statement announcing the plant's plans to build the cooling towers.

Construction on the cooling towers started in 2009. They were completed in 2012. Less than five years later, they were dynamited to smithereens.

WATCH: The implosion of a pair of cooling towers at the former Brayton Point power-plant in Somerset. @wbz #Swansea #Somerset pic.twitter.com/XKBmumQ3iR

— Anaridis Rodriguez (@Anaridis) April 27, 2019

During the brief period during which the towers stood, they became prime targets for environmental activists determined to force Massachusetts and other New England states to stop using coal and natural gas as a source of electricity. Hundreds of people showed up for a July 2013 protest that ended with dozens of arrests.

For the environmentalists, seemingly no amount of retrofitting or pollution-reducing improvements at Brayton Point would be sufficient. Signs carried at the rally called on lawmakers and then-Gov. Deval Patrick, a Democrat, to "Shut Down Brayton Point."

It took a few years, but the protesters got what they wanted.

Despite that $500 million investment in making the plant's cooling system more environmentally friendly, Dominion Energy announced in 2013 that it would close the Brayton Point plant by 2017, in no small part because other environmental regulations made it financially infeasible to keep the coal-fired plant operational. A proposal to convert the coal-fired plant to burn natural gas instead was rejected.

"It's a very clear indication," Jonathan Peress, director of the climate change program at the Conservation Law Foundation, told the Associated Press shortly after the plant's closure was announced, "that coal-fired power is no longer economically viable."

That might be debatable. What's clear, however, is that Brayton Point was no longer politically viable.

Environmental Tradeoffs

There's no denying that offshore wind power is more environmentally friendly than burning coal to make electricity. But there are tradeoffs. For all its drawbacks, the Brayton Point plant provided reliable generating capacity that far exceeds even the best estimates for the Martha's Vineyard wind project, which will tie into the power grid where the coal-fired plant once did.

Even if you assume robust breezes around the clock, the Vineyard Wind project will top out at 800 megawatts when it is fully operational. That's enough to power roughly 400,000 homes—less than one-third of what the Brayton Point plant once served. And that's despite being one of the larger offshore wind projects among those recently proposed by states along the Atlantic coast.

The main problem, of course, is that when the wind isn't blowing, other sources of power will have even more slack to pick up.

Those consequences are already evident. Last winter, New England power plants burned record amounts of oil, causing the region's carbon emissions to skyrocket. "Carbon-dioxide emissions across ISO New England's power network jumped 51% in January to nearly 4.2 million metric tons from a year earlier," Bloomberg reported in February. The region relies on imported oil and natural gas to provide energy, since there are few natural gas pipelines linking the area to more gas-rich parts of the United States.

The situation at Brayton Point is emblematic of bigger problems with climate change policy at the federal level, says Philip Rossetti, a senior fellow for energy policy at the R Street Institute, a free market think tank based in Washington, D.C.

"A politician will get wowed by some technology and think that if only there's a mandate or a tax credit in place then it will be successful in the market," he tells Reason. "At the end of the day, though, all producers in the energy sector are subject to market forces, and it is the market conditions that will broadly determine what technologies will be deployed and which will fail."

The federal government can try to influence those markets with subsidies and tax breaks, but consumers ultimately have to deal with the tradeoffs that come with government support for less reliable forms of energy. And even the massive tax breaks included in the Inflation Reduction Act, meant to offset the construction costs of offshore wind projects and other forms of green energy, can't make those forms of energy more reliable.

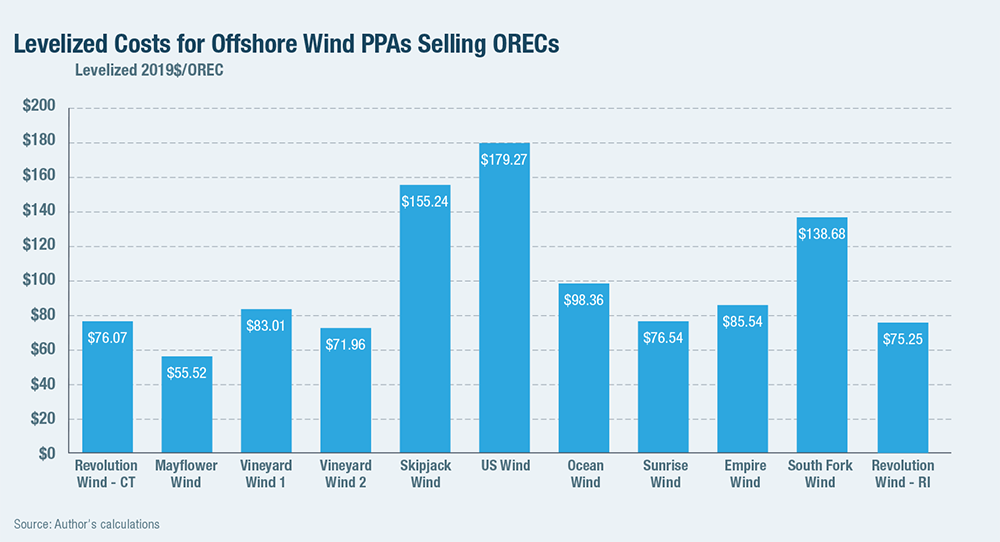

And less reliable energy is more expensive. According to the Energy Information Administration, the "levelized cost"—the cost to produce a single megawatt-hour unit of electricity—for the Martha's Vineyard wind project is more than $70. Other ongoing offshore wind projects have even higher costs.

By comparison, the levelized cost for a natural gas-fired power plant averages about $38, around half of what offshore wind costs. Even if coal-fired plants are deemed too dirty and too politically toxic to continue running, a more marginal shift to natural gas would ensure more reliable and affordable energy.

The evolution of the Brayton Point facility, then, shows the two paths that policy makers can take to balance environmental concerns with the market forces that can be ignored but not avoided. On one hand, regulators can push for incremental improvements like building cooling towers to prevent dumping hot water into a marine environment, or for transitioning coal-burning plants toward less dirty alternatives like natural gas.

On the other, there's the blow-up-the-towers option. That succeeded in taking a coal-powered plant offline, yes, but at the cost of a less reliable electrical grid and a less robust wind-powered alternative. It's also a route that discourages future investment in energy—other companies might be less willing to invest $500 million in new cooling towers, for example, after seeing what happened to the Brayton Point plant shortly after they were installed.

Like in all markets, both the supply and demand sides of the equation matter. Indeed, even though Biden's photo op at Brayton Point was mostly focused on the supply of electricity—as in, how electricity is generated—his speech and the executive orders he was touting also deal with demand. Among other things, Biden promised new subsidies "to pay for air conditioners in homes, set up community cooling centers in schools where people can get through these extreme heat crises."

Subsidizing demand while crimping supply is a recipe for problems.

There's no doubt that the coal-fired power plant at Brayton Point damaged the surrounding environment, and that coal-fired plants in general cause more emissions than other types of power-generating stations.

But big decisions come with big tradeoffs—and Biden's promise of "a big transition" to clean energy might will not arrive without costs of its own.

Show Comments (68)