Field of Welfare: How COVID Funds Might Build a Money-Losing Ballpark in a Cornfield

Is there a single movie more tied up with lousy government policy than Field of Dreams?

As Major League Baseball on Thursday takes to a remote Iowa cornfield for its second annual Field of Dreams game in commemoration of the nostalgic 1989 Kevin Costner film, it's worth reflecting that at least five different governments are cobbling together a deal to spend a combined $45 million in taxpayer money on a proposed 3,000-capacity stadium to be built on the site of the movie and game.

And, if politicians get their way, the finishing touches on the financing will come from the federal government's coronavirus relief fund.

The details, as laid out last week in a terrific Des Moines Register article, are, with the exception of the COVID-19 twist, distressingly familiar for anyone who has followed the $20 billion sports-facility-welfare building boom that began almost immediately after Field of Dreams wrapped its theatrical run. There's the tax increment financing, the gauzy promises of future economic development ("a very good investment in the future"), the hand-waving at the overwhelming evidence to the contrary, the extraction and proposed expenditure of hotel taxes, and the hand-over-heart appeals to the hoariest of Americana.

"We have to fund projects that can bring us together," Dubuque Mayor Brad Cavanagh told the newspaper. "We have to find things that are going to lead us in a direction of unification rather than tearing us apart."

As you read the dizzying Register passage below about the overlapping governmental shovelings into this heartland sinkhole, here are some contextual data points to keep in mind: Dyersville, Iowa, the site of the project, has 4,000 residents; its annual budget in fiscal year 2021–22 was $9.5 million. Dubuque, the nearest city (25 miles away) of any size (60,000), had an operating budget that year of $139 million. The government of Dubuque County (pop. 99,000) spent about $70 million in 2021–22.

So that's around $220 million a year the relevant local administrations spend, compared to a price tag of $50 million for a stadium whose main projected revenue would come from one (currently non-guaranteed) baseball game per year.

We may be talking Iowa here, but the governmental financing package is positively Byzantine:

In an application to the Iowa Economic Development Authority, submitted in May and adjusted in June, the city of Dyersville asked for $12.5 million in funding through Destination Iowa, Gov. Kim Reynolds' $100 million pool for tourism projects, funded with federal American Rescue Plan Act coronavirus relief money. …

A Destination Iowa award is only one piece of potential taxpayer funding for the project. The city of Dubuque committed $1 million. Dubuque County committed $5 million. The city of Dyersville committed $1 million and plans to offer another $13 million in tax increment financing.

The U.S. Economic Development Administration granted Dyersville $1.5 million to build water and sewer lines last September. The state of Iowa kicked in another $11 million of federal funds for the same purpose in January.

All told, the Destination Iowa grant would raise the amount of public funding to $45 million—90% of the budget for the $50 million stadium. That does not count $500,000 contributed by Travel Dubuque, a local tourism nonprofit largely funded with hotel-motel tax revenue.

Remember when politicians used to complain about austerity?

The $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan, enacted in March 2021, was sold as helping the country and the economy to recover from COVID-19, not building sparsely-used entertainment venues years in the future. (In actuality, the money has been used to bail out government-run golf courses and hand out bonuses to state employees, among other boondoggles.)

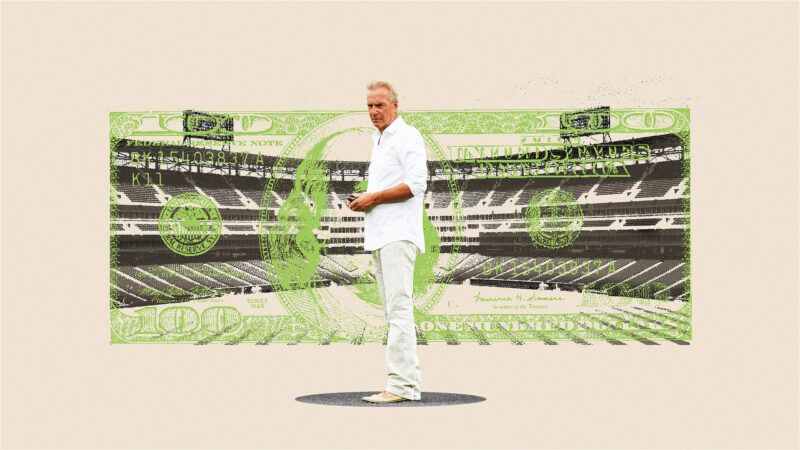

Instead of rescuing America, the proposed repurposed Rescue Plan funds would greatly help the bottom line of Hall of Fame White Sox slugger, television personality, and testosterone-booster pitchman Frank Thomas, who earned more than $100 million during his playing career alone.

The stadium would be owned by This is Iowa Ballpark, a new nonprofit controlled by the city of Dyersville, Dubuque County, Travel Dubuque, the Dyersville Economic Development Corp. and Go The Distance, a development group helmed by MLB Hall of Famer Frank Thomas.

Go The Distance, which owns the movie site, announced in April that it plans to spend $80 million to develop the area surrounding where the stadium would stand. Its plans call for nine baseball and softball fields, dorms, a fieldhouse, a fishing pond, walking trails, an RV park, an amphitheater and a 104-room hotel.

According to Dyersville's application for Destination Iowa funds, This is Iowa Ballpark would lease the stadium to Go The Distance.

The history of local governments building sports facilities and then leasing them to private (and oftentimes, rich) owners is filled with sorrow. Especially in smaller towns.

"These partners have heard the message from the movie Field of Dreams: 'If you build it, they will come,'" New Jersey Gov. Christine Todd Whitman said in 2000, paraphrasing the movie's most famous line while breaking ground on a $24 million minor league ballpark in Camden, one of seven the Garden State financed from 1994 to 2001. "Soon we will see a field of dreams right here in Camden, and my prediction is they will come."

By 2015, Whitman's taxpayer-financed stadium stood empty. (Read Eric Boehm's 2019 article about New Jersey's calamitous stadium welfare binge.)

All of this wasted human effort has been depressingly predictable and exhaustively documented, for decades. Back in 2000, economist Raymond Keating made the stone-obvious yet apparently still elusive point that, "Another major downside to government-built and -owned ballparks is that clubs are transformed from owners to renters. It is always easier for a renter to move to get a better deal. So, government officials who advocate taxpayer-funded sports facilities to attract or keep a team virtually ensure that teams will continue issuing threats and moving."

Kennesaw State University economist J.C. Bradbury (who wrote for Reason about Atlanta Braves stadium welfare back in April) collaborated with fellow academics Dennis Coates and Brad Humphreys on a paper earlier this year surveying more than 130 studies of the economic effects of subsidized sports-venue construction over the past three decades. Conclusion?

"Nearly all empirical studies find little to no tangible impacts of sports teams and facilities on local economic activity, and the level of venue subsidies typically provided far exceeds any observed economic benefits," the authors wrote. "In total, the deep agreement in research findings demonstrates that sports venues are not an appropriate channel for local economic development policy."

But also: "Despite the consensus findings of economic studies that the benefits of hosting professional sports franchises are not sufficient to justify large public subsidies, taxpayer funding for these subsidies continues to grow. This paradox reveals a disconnect between findings in economic research and policy applications that requires correcting."

Bradbury's Twitter reaction to the Register article (in which he's quoted): "Another nomination for the Hall of Terrible Ideas."

When grown men choke up as they recount Field of Dreams, no doubt they are thinking of the film's final scene, where Kevin Costner, in the ballpark he irrationally plowed a cornfield to build after listening to the voices in his head, is finally able to play a restorative game of catch with his long-dead dad. As the camera pans out we see a line of cars in the distance, heading toward the Dyersville ballpark, in fulfillment of a prophecy given just minutes before by the novelist character played by James Earl Jones:

People will come, Ray. They'll come to Iowa for reasons they can't even fathom. They'll turn up in your driveway not knowing for sure why they're doing it. They'll arrive at your door as innocent as children, longing for the past. Of course, we won't mind if you look around, you'll say. It's only $20 per person. They'll pass over the money without even thinking about it.

If baseball fans and cineastes want to cough up $20 ($48 in today's money) to feel the magical realism up close, I'm all in favor. But taxpayers with all manner of entertainment tastes have for too long been unwittingly passing their money to subsidize rich people profiting off the nostalgia industry. There is nothing "innocent" about this racket; it's morally obscene.

As Dan Moore concluded last week in an outstanding retrospective of Camden Yards, the heavily subsidized and deeply influential Baltimore Orioles stadium that just celebrated its 30th anniversary: "At a certain point—stretched too far, tested by too many unignorable, ignominious costs—the hypnosis becomes untenable, and losing yourself earnestly in a game, a season, or in the longer-tail travails of your favorite team becomes impossible, no matter how beautiful or beloved your surroundings. You find yourself thinking, instead, about how much the person sitting in the owner's box behind home plate or above the 50-yard line has profited from the one-sided partnership that you, as a taxpayer and fan, have unwittingly borne the economic brunt of."

BONUS LINKS: I critiqued Field of Dreams last week on the Gutting the Sacred Cow podcast. And Nick Gillespie interviewed Bradbury in 2013 about why stadium subsidies always win:

Show Comments (32)