It's OK To Warn Sexually Active Gay and Bisexual Men They're at Greater Risk of Monkeypox

Good public health messaging must be comprehensible, accurate, and actionable.

America is approaching 10,000 diagnosed monkeypox infections, a higher number than any other country in the world.

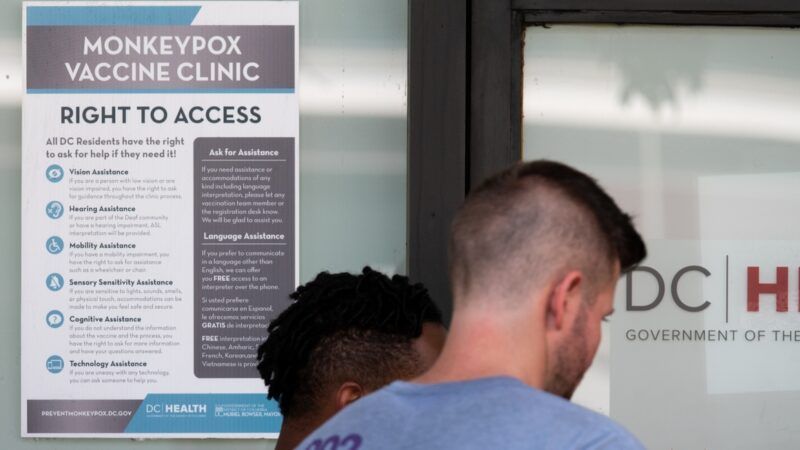

The feds are still struggling to get doses of the monkeypox vaccine from Denmark to the U.S. and over to local health agencies in the cities that have seen the most infections. Due to the lack of vaccines, city and county health departments are carefully portioning out doses, which necessarily means determining which citizens are at the greatest risk of unwittingly contracting and transmitting monkeypox.

And this, to be clear, is overwhelmingly men who are sexually active with other men. As a gay man in Los Angeles, I managed to get my first dose of the Jynneos monkeypox vaccine last week. I'm supposed to get a second dose at the end of August, but the vaccine shortage has Los Angeles County focusing on getting first injections out and worrying about the second shots later.

I have also, as a responsible person who doesn't want to be covered with painful rashes and blisters, adjusted my own behavior and have not for the past couple of months been rushing out to have lots of sexual activity. Monkeypox is not technically classified as a sexually transmitted infection—it can be exchanged through saliva and through contract with the aforementioned rashes or anything the rashes have come into contact with—but the strain that is currently spreading across the U.S. seems resistant to spread through short-term casual contact. Instead the evidence strongly shows that it's being spread through bodies rubbing against each other via sexual activities. There have been a few exceptions, but sex between men has almost entirely been the mechanism for monkeypox's current spread. According to the current data from Los Angeles County, 99 percent of the infected are men. Less than four women number among the 496 infections in the county database.

Unfortunately, while some health officials have been very good about informing sexually active gay and bisexual men about this risk, there is still a remarkable unwillingness among some officials to say outright that sexual activity can be risky and that this primarily affects gay and bisexual men.

Los Angeles County's prevention page does clearly explain how sexual activity with somebody with monkeypox lesions can spread it, and the background section notes that most cases have been among gay and bisexual men. It does, of course, note that anybody can get monkeypox through being in close contact with someone who is infected, but it provides a clear sense of who needs to be the most concerned.

Contrast that with Oregon public radio's interview with Dr. Tim Menza, an adviser with the Oregon Health Authority. When interviewer Jenn Chavez asks him the best ways to reduce the risk of contracting monkeypox, Menza flat-out refuses to use the word "sex":

And then the things that then move up in scale are things that include more prolonged skin-to-skin contact. Like perhaps massaging an area with skin that is affected by [monkeypox], or hugging in contact with skin that is affected by [monkeypox]. Or perhaps cuddling. The other thing is we know that when we talk about respiratory secretions we think about saliva too. So things like kissing or sharing a toothbrush might be a little bit higher risk.

And then the things that have the most risk is when there's that really direct prolonged skin-to-skin contact with the sores, the scabs or the fluids of the rash.

Yes, it's true that such prolonged exposure need not be sexual, but it's just incredibly bad to not actually say sex. It's Chavez who finally brings up the fact that transmission is primarily taking place between men having sex with each other. And this is part of Menza's response:

In the United States, we know that people assigned male at birth who have sex with men and people assigned female at birth, including at least one pregnant person, have been affected by [monkeypox] in Oregon. We know that cisgender, men and nonbinary people are affected by [monkeypox]. While most identify as gay or queer and report close contact with people assigned male at birth, we have cases that also identify as straight and bisexual and report close contact with people assigned female at birth.

This absolute mess of a response essentially says "monkeypox infects all kinds of people." Menza is not painting an accurate picture of who is at the greatest risk. Perhaps he doesn't want women or heterosexual men to think they they're immune. But the end result is an incomprehensibly muddled public health message that doesn't say what it needs to say.

Menza says the state tends to rely on "community partners to do a lot of the community engagement and communication to folks who are most affected by" monkeypox. So the state's health department is outsourcing the effort to reach the people most at risk and is using its much larger media access to send out muddled messages that inaccurately imply that we're all at equal risk of infection.

Similarly, when President Joe Biden's administration declared monkeypox a national emergency last week, the "money quote" from Secretary of Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra was, "We urge every American to take monkeypox seriously, and to take responsibility to help us tackle this virus." But most Americans don't actually have to do anything at all, and many of the Americans who do need to do something—gay and bisexual men—can't "tackle this virus" because Becerra's own agency has done a dismal job of getting vaccines where they need to be.

And so gay and bisexual men have to take responsibility for doing what we can to temporarily reduce the risk of helping monkeypox spread.

The emphasis here is on "temporarily." Part of the media handwringing over monkeypox (and there's been so much of that that it arguably serves as the public health messaging the government is failing to provide) has been whether it's appropriate or even effective to be attempting to convince gay men to engage in "abstinence" given the general experience of stigma that was the hallmark of the years of the worst of the HIV crisis. But there are some very significant differences here.

First of all, HIV fueled an already existent stigma about homosexuality that has since significantly declined. Yes, there are some antigay conservatives out there who are blaming the gays for the spread of monkeypox, but they were going to do that regardless of what public health leaders say. And they just don't get the public attention that they used to back when everybody was afraid of HIV. Health departments are not meaningfully protecting gay and bisexual men from this "stigma" by being shy about providing proper warnings about sex.

The other big difference was at the time, HIV was deadly and uncurable. Part of the stigma was connected to a sense that if you were gay and sexually active in any way, you would get it and you'd have to live with it until you died. HIV is still not quite curable, but it is suppressible and much of its stigma is now long gone.

Monkeypox is a miserable, painful experience that you don't want to go through, but it's rarely fatal and it's over in about a month. It's not HIV. It's a serious problem, but it's a temporary one. This is not some blanket, long-term demand for "abstinence."

It's simply not good public health messaging to tie these two completely unrelated viruses together simply because they're affecting the same demographic. That's actually something the antigay types are doing. There's a lesson there.

Show Comments (144)