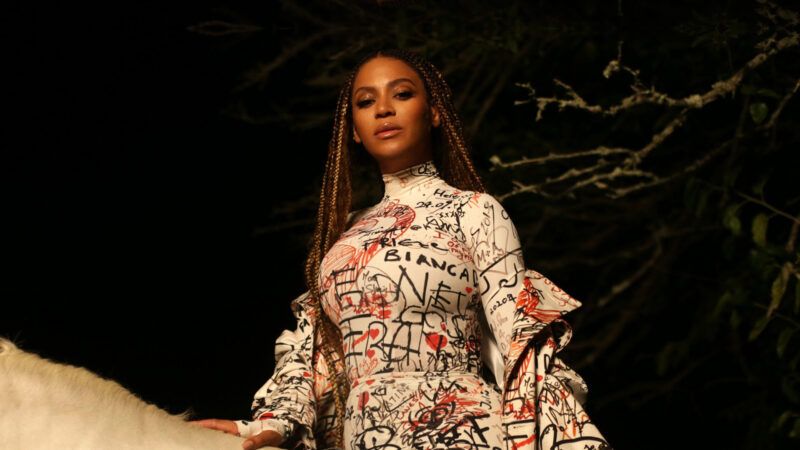

Beyoncé, Under Fire for Using an 'Ableist Slur,' Chooses Self-Censorship

"Spazzing on that ass" does nothing whatsoever to harm people with cerebral palsy.

"I'm Ike Turner, turn up baby, no, I don't play/Now eat the cake, Anna Mae," rapped Jay-Z on Beyoncé's 2013 hit "Drunk in Love." It was a reference to Ike and Tina Turner's abusive relationship, and to the memorable diner scene from the 1993 biopic, What's Love Got to Do With It, in which a jealous Ike smashes cake into Tina's face.

It's a clever line. It also arguably makes light of an abusive marriage. But that's not the phrase that Beyoncé has decided to scrub from her discography. She's striking "spazzing on that ass," from her new track, "Heated."

According to a certain subset of disability activists, any use of the word spaz or its derivatives is marginalizing. "Disabled people's experiences are not fodder for song lyrics. This must stop," tweeted the disability rights organization Scope. "When Beyoncé dropped the same ableist slur as Lizzo on her new album, my heart sank," reads the headline of a Guardian article by the activist Hannah Diviney, who wrote that she has "no desire to overshadow" Beyoncé's "lived experience of being a black woman…but that doesn't excuse her use of ableist language." Beyoncé's publicity team quickly responded to the heat, saying she'd be changing that line and removing the word from the song, just as fellow artist Lizzo did two months ago when she came under similar scrutiny, led by some of the same activists.

But "disabled people's experiences" are not being used as fodder for song lyrics. "Spazzing on that ass" does not reference a person with cerebral palsy having spasticity—muscle stiffness that hinders mobility. In parts of the Anglosphere, the word spaz is seen as a terrible slur; in America, where Beyoncé is from, it refers to freaking out, to moving crazily, to becoming overly excited, or, possibly, to something failing to function properly. You can see how that meaning evolved from the slur, and you can see why that would aggravate some listeners. But like "paddy wagon" before it, the word has lost those connotations for many people who use it. If these activists are really concerned about the harm the word does, which seems more harmful: constantly reminding people of the term's origins, or letting it continue to drift away from its original connotations?

So @Beyonce used the word 'spaz' in her new song Heated. Feels like a slap in the face to me, the disabled community & the progress we tried to make with Lizzo. Guess I'll just keep telling the whole industry to 'do better' until ableist slurs disappear from music ????

— Hannah Diviney (@hannah_diviney) July 30, 2022

Beyoncé and her publicity team are well within her rights to make a calculation about how to best curry favor with her audience. Like Lizzo before her, who conceded to the activists and cut the same word from an already-released song, Beyoncé may feel the shortest line to profits is to cultivate a sensitive, conscientious image. She has always been keen on an empowerment-lite aesthetic, choosing to dance in front of the lit-up word "FEMINIST" and sampling the Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie speech "We Should All Be Feminists" on her song "Flawless."

But it's pathetic to give these activists this veto power. Rap tends to use words in ways people actually talk, not the platonic ideal of how people should talk if they want to be maximally sensitive. Beyoncé comes from that tradition, and her earlier work—like that shameless reference to Ike and Tina—is in line with that. It's possible that Beyoncé was legitimately unaware of the term's origin, and that she actually cares that her words might offend some disabled people. The more plausible explanation is that she has an image to uphold and has chosen the path of least resistance, bending when needed to merit the good publicity to which she has become accustomed. Regardless, her decision suggests that perhaps she didn't mean what she initially said; that words can be substituted on demand; that she has little attachment to the art she released.

You can sometimes judge how much a word is actually considered a slur by how publications choose to handle mentions of the term. The New York Times, CNN, The Washington Post, and USA Today have all clearly named the word in their writeups of the saga. But just last week, USA Today covered a whole controversy involving the word midget without ever actually saying the word, using all kinds of euphemistic contortions to get around mentioning it. In the Times' coverage of science writer Donald McNeil's firing—for clarifying whether a student was talking about the word nigger when discussing an instance of racist language—the paper wouldn't say what the actual word was, eschewing full context in favor of stilted descriptions.

The fact that so many places spell out the word spaz, even at a time when many papers' editorial standards allow for euphemizing, is decent evidence that it's not perceived as a terrible term in the U.S. It's a word with multiple meanings, all dependent on context, long disconnected from the origins. And it's hard to see how anyone's plight is materially helped by getting artists to excise it on demand.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

How dare she? What would a black woman now about hardship?

But "disabled people's experiences" are not being used as fodder for song lyrics. "Spazzing on that ass" does not reference a person with cerebral palsy having spasticity—muscle stiffness that hinders mobility. In parts of the Anglosphere, the word spaz is seen as a terrible slur; in America, where Beyoncé is from, it refers to freaking out, to moving crazily, to becoming overly excited, or, possibly, to something failing to function properly. You can see how that meaning evolved from the slur, and you can see why that would aggravate some listeners. But like "paddy wagon" before it, the word has lost those connotations for many people who use it. If these activists are really concerned about the harm the word does, which seems more harmful: constantly reminding people of the term's origins, or letting it continue to drift away from its original connotations?

This quote reminded me of Royal Marshall, producer of "The Neal Bortz Show" interpreting the ”Boo Got Shot" news story in emaculate, stainless, seamless Queen's English:

Boo Got Shot!

https://youtu.be/2SK6_Di_3O0

🙂 :). 🙂

Why are you being divisive by printing this article? Just let it go and talk about tax rates or something. Quit fanning the flames of kultur war.

Include some audio of Nick kvetching about culture war and how this isn't serious stuff.

Extreme triggering warning: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gG98X8NsMKs

It just doesn't matter.

I've noticed people increasingly cannot grasp the idea of deprecating nicknames becoming terms of endearment.

Look no further than Yankees.

Yeah. "Babe" Ruth? How dare they name him after the pig from that movie.

Or the candy bar even!

Or your mom!

"YANKEE?!?!? Get off'n my plantation, you, you Carpetbagger!"

https://youtu.be/J_FlzLNNPb4

They act like a gang, perhaps they should name themselves the crips. I think Southpark weighed in on this

"CRIPPLE FIIIIGHT!"

Sad thing is, I've seen this in real life over handicapped parking spaces and electric carts at my store. Thanks, Daddy Bush for the ADA!

I can't wait for some black activist to sue everyone who uses any variation of nigg* in any rap song. Ought to start a pool.

As long as they don't go after rock music from the '70s

Use of the word 'slur' is an ableist denigration of 80-yr.-old white dudes with dementia.

Good one.

Agree. It's ableist to even try and describe ableism.

Whenever a celebrity gets in "trouble" for doing or saying something controversial, my first question is whether (s)he set it up for the sake of publicity. I'm not saying that's always the reason, just that it's possible.

False flag. It's the celerity way.

Status falling, just get something controversial out to the media.

"Rock star marries sister!"

It's the National Enquirer standard.

This is America. One does not need to be smart to become rich. Just controversial.

Winston Smith busily at work in his Ministry of Truth cubicle erasing words from the language. Let's all applaud Winston Smith.

If you think this is bad, wait until you find out what they did to the N-word.

Hey tony, how many people have died cuz of Dave chappelle? Or were you just “spazzing” out when you said “people will die!”?

Oops. Shouldn’t have said that. I’ll have to go into timeout with queen Bey. That could be fun. Definitely would like to be “spazzin’ on that ass”!

D’oh!

Probably some. As our cherished small-minded idiots like to remind us, trans people have high rates of suicide, which is obviously why we must mock and doxx them, especially when they're young.

Mentally ill people have a high rate of suicide.

Getting your junk cut off doesn’t fix that.

Suicidal people have a high rate of suicide. The answer isn’t to give them whatever they want. That’s called “taking yourself hostage.”

I don’t negotiate with terrorists.

"The answer isn't to give them whatever they want."

So you want the government to punish people who get transition treatments?

Just how far is this "government agent in the exam room" bullshit going to go?

https://twitter.com/GPrime85/status/1547245685690482696?s=20&t=fo9WWPHB3PSLujBo3EpWzQ

“I’m going to hold my breath until you say men can get pregnant!”

“Stop it! You’re killing her!”

No tony, you said the trannies would “die!” cuz Dave chappelle “gave permission to violent bigots” to harm them. You never said anything about suicide.

Ya wacky little goalpost shifter, you. Haha.

So do fire fighters?

What's that got to do with it?

In fact, doesn't it support the oft deflected suggestion that there is something mentally wrong with trans people?

Which I've conceded for this argument.

I'm just wondering why it's then OK to start harassing and doxxing these suicidally-prone mental cases.

Too much math for a cunty schoolyard bully?

Why do I get the feeling that, rather than arguing a point Tony, your posts here just get you aroused? And the retorts just get you off?

Seek help! Lest you end up like the trans people you mention.

Nattering Nabobs of Negativity?

I tip my gin and cloves to him!

Did Rihanna get in trouble for saying "whips and chains excite me"? What would her ancestors think?

Oh-oh! What's DJ Dave the Spazz going to do?

I guess The Elastik Band is in huge trouble now.

This article left me feeling like a retard for having perused it.

RETARD!!!

I just came for the comments. I deleted all of Beyonce's music from my iTunes and iPhone a while back, and Cher, Madonna, etc

She could take the conservative approach and relentlessly mock and doxx the supposedly mentally ill on the internet, especially when they're children.

Actually, I think that's now the entire Republican national policy platform: be cruel to the mentally ill.

We mock you because your a retarded Marxist, you being retarded just makes it easier, that doesn't mean that libritarians hate all retards

They're mocking LARPers, poseurs and signalers like you, Tony Baloney.

So trans people aren't mentally ill?

Why do you refuse to advocate for liposuction for anorexics?

I wasn't talking about actual trans who're rarer than unicorns, but the perverts, alphabet sex cultists and attention whores that make the up 99.99% of claimants.

According to your previous comment, they are more inclined than the general population to be so.

This goes all the way back to "Lonesome" George Gobel always saying "Don't mock the afflicted".

Bake the cake bitch!

So people all made a bunch of free choices without any government interference, but it's tyranny.

I don't think this philosophy is very rigorous.

Hey Tony.

It is actually possible to have distaste for hate mobs without calling for government interference.

I have a distaste for bread & butter pickles.

Let's spend years on end talking about that individual whim that has nothing to do with politics or government, shall we?

Don't threaten me with a good time.

Who is trying to force you to eat those sandwiches?

Let's spend years on end talking about that individual whim that has nothing to do with politics or government, shall we?

So . . . you never talk about anything that doesn't have directly to do with politics or the government?

The KKK doesn't have anything to do with politics or the government - are they off limits, too?

You mean like the ACLU fighting for the rights of Nazi's to march?

Please stop pretending that these fascists are arguing in good faith.

I think we have a winner!

Or, to use an alternative phrasing "Folks, get a life!"

'.....Rap tends to use words in ways...... uneducated, unsophisticated, brainless, dumb, idiotic , imbecilic, moronic, stupid, witless, foolish, senseless, silly......people actually talk....'

Ding! Ding! Ding! We have a winner for best comment of this thread.

I read through some other lyrics from the album. The whole thing is vulgar trash. "Spaz" is the least of its problems, yet here we are.

I would have maximum respect for her if she said "fuck off, get over it"

But she is basically the BIPOC queen for retarded liberals, so she can reap what she has sown.

Some people just want to get mad about stuff.

“Everything is so terrible and Unfair!!!!!” (Tm)

It’s a religion. A toxic one.

You can see how that meaning evolved from the slur, and you can see why that would aggravate some listeners. But like "paddy wagon" before it, the word has lost those connotations for many people who use it.

That is totally gay.

What a queer comment.

No no no no no. Clearly she mispoke and meant to say spunkin' on that ass.

Either way - I approve.

How can she spunk with no dick? Uh-oh!...

I met her in a club down in old Soho

Where you drink champagne and it tastes just like

**** Cola

Rode in an Escalade in Cabo. Driver told me about celebs he’s driven. Said Jay-Z and Beyonce works only talk to him through their security people and that Beyonce is a total bitch. Said Jennifer Aniston was very friendly lol

Goldmember was on tv the other night. Watched a little of it. Man, Bey was hot back then. Then again, so was Brittany.

Bey or Brittany, 2022 version: would or wouldn’t? Discuss.

Keep in mind, your answer, whatever that may be, will make you a racist.

The appropriate response is to completely ignore these people or say "Oh, I didn't mean it that way and neither does anybody else who says it." then keep using it.

Why are some words considered slurs, but if you use another word with the same meaning, it's not controversial? Doesn't it just have to do with the context in which someone says it? It was not Beyonce's intention to mock someone with an illness or injury. Seems crazy to correct a mistake because someone read something into one of your lyrics. What a precedent to set.

Yes. Context matters.

The media knows this and exploits it. By taking things out of context.

The always-looking-for-something-to-whine-about PC crowd has learned how to exploit this as well. There are large swaths of GIECO Cynthias focused on words out there just waiting to pounce on anything they can. They thrive on it.

I hope the woke do not figure out what the acronym for NWA is, the band that created one of the 20th century's most remarkable and influential albums, Straight Outta Compton. Yet somehow I think great rap artists will not bow down to the word police any more than they ever have, one of the powerful aspects of the genre.