Lady Chatterley's Lover Case Dealt a Blow to U.S. Book Censors

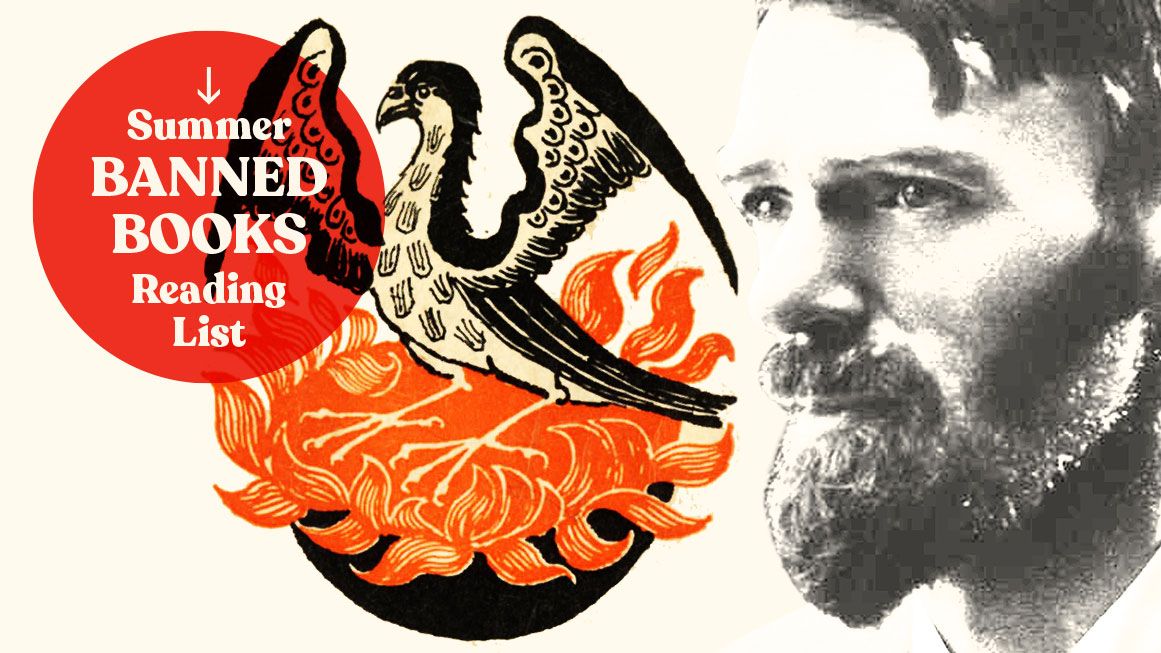

Up through the 1950s, federal agents kept confiscating books they deemed obscene. But in 1959, a judge ruled that D.H. Lawrence's book deserved First Amendment protection.

The English novelist D.H. Lawrence published Lady Chatterley's Lover privately in 1928. The book was declared obscene in the United States in 1929, and agents from the Post Office and the U.S. Customs Service began seizing any copies they encountered. That same year, the Boston bookseller James A. DeLacey was fined and jailed for four months under Massachusetts' obscenity statutes for selling five copies.

The federal government left book banning largely to the states until the passage of the Comstock laws in 1873. Named after their chief proponent—Anthony Comstock, the founder of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice—the laws barred mailing any "obscene, lewd, or lascivious book, pamphlet, picture, paper, print, or other publication of an indecent character."

Up through the 1950s, federal agents kept confiscating books they deemed obscene. But in 1959, U.S. District Judge Frederick van Pelt Bryan ruled that Lady Chatterley's Lover deserved First Amendment protection, and he dealt the censors a major blow in the process.

To reach his decision, Bryan deployed the obscenity test outlined by the Supreme Court in 1957's Roth v. United States: "whether to the average person, applying contemporary community standards, the dominant theme of the material taken as a whole appeals to prurient interest."

Lawrence's book describes an affair between an upper-class woman and a working-class man. With this story, Bryan wrote, Lawrence attacked "what he considered to be the evil effects of industrialization upon the wholesome and natural life of all classes in England." While the novel contains "a number of passages describing sexual intercourse" and "four-letter Anglo-Saxon words," it was "replete with fine writing and with descriptive passages of rare beauty," leaving "no doubt of its literary merit." Bryan concluded: "The dominant theme, purpose and effect of the book as a whole is not an appeal to prurience or the prurient minded."

As far as community standards were concerned, Bryan held that "at this stage in the development of our society, this major English novel, does not exceed the outer limits of the tolerance which the community as a whole gives to writing about sex and sex relations." Thus, the book was not legally obscene, and people could not be punished for selling it. Lady Chatterley's Lover was "entitled to the protections guaranteed to freedoms of speech and press by the First Amendment."

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Lady Chatterley's Lover."

Show Comments (14)