Judge Tosses Maryland's Highly Gerrymandered Congressional Map

Advanced statistics and redistricting reformers combined to kill one of the country's worst gerrymanders.

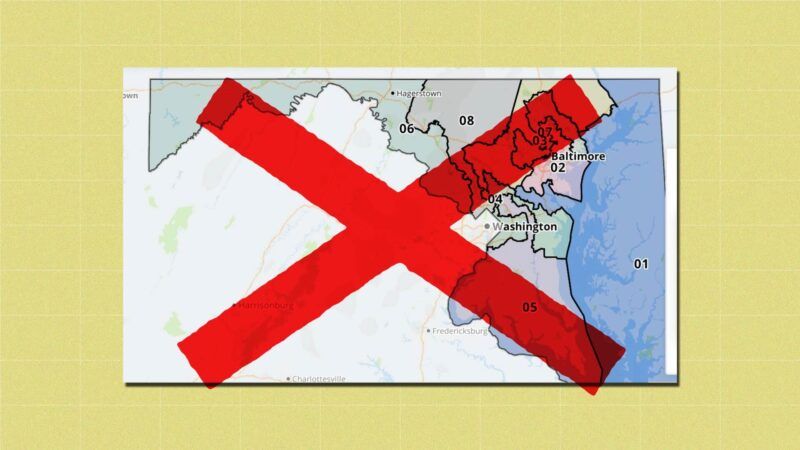

Calling it "an extreme gerrymander," a Maryland judge on Friday tossed out the state's new congressional district map and ordered state lawmakers to produce a new one before the end of the month.

In the ruling, Judge Lynne A. Battaglia said the eight congressional districts drawn by the Democrat-controlled state Legislature lacked compactness and demonstrated a disregard for existing political boundaries like counties and cities. The map "subordinates constitutional criteria to political considerations," Battaglia wrote, and in doing so violates the Maryland Constitution's equal protection and free elections clauses. It's the first time in Maryland history that a judge has discarded a redistricting map for being too politically slanted, according to The Washington Post, which is really saying something given the state's recent history.

The congressional map used in Maryland for the past 10 years was one of the most highly gerrymandered in the country—even though Republican gerrymanders in places like North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin attracted more attention to the problem of politically motivated mapmaking. That's part of the reason why Maryland's congressional delegation has been split 7–1 in favor of Democrats for the past decade.

This time around, Democrats in Annapolis drew an even more gerrymandered map that would have given them an electoral edge in all eight of the state's districts by carving up Maryland's deep blue Baltimore/Washington corridor so that nearly all of the state's congressional districts include some part of it. The new map received a grade of "F" from the Princeton Gerrymandering Project, which grades congressional maps on partisan fairness, geographical compactness, and other factors.

In the ruling, Battaglia pointed to how the Maryland map scored poorly in several metrics used to access the compactness of political districts. These mathematical formulas are imperfect ways of assessing congressional districts—not every district ought to be a perfect circle, of course. But, as I argued in a 2018 feature for Reason, that sort of statistical analysis is vital for lawmakers and judges to use when assessing the question of how much gerrymandering is too much.

Battaglia's ruling bears that out. She points to the fact that Maryland's districts scored worse than all but two other states on the Polsby-Popper scale—a metric that measures the ratio of a district's area against a theoretical circle with the same circumference as the district's perimeter. Maryland scores equally poorly under the Reock metric, which requires drawing the smallest possible circle that would encompass all points of a district, then comparing the area of the circle to the area of the district.

When compared to other current and former congressional maps, the scores given to Maryland's maps compare "very poorly relative to anything drawn in the last fifty years in the United States," wrote Battaglia in Friday's ruling.

Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan, a Republican, called Friday's ruling "a monumental victory for every Marylander who cares about protecting our democracy, bringing fairness to our elections, and putting the people back in charge."

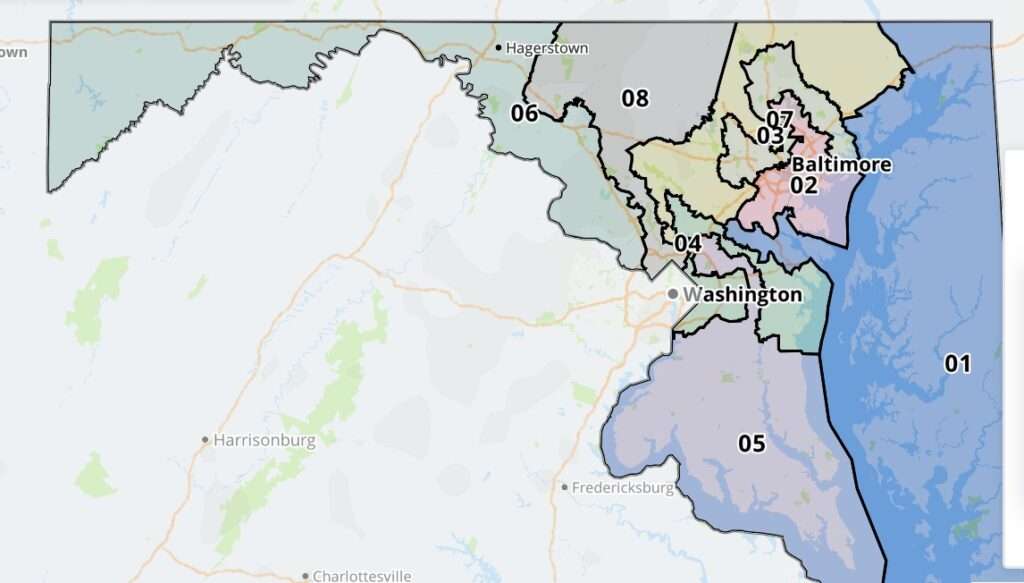

Hogan encouraged state lawmakers to respond to Battaglia's ruling by voting to adopt a map drawn by the Maryland Citizens Redistricting Commission, a group that included three Republicans, three Democrats, and three politically unaffiliated residents of the state.

Though the commission was powerless to implement its vision, the map it produced is undeniably fairer than the one approved by state lawmakers and ultimately rejected by Battaglia. The districts make geographic sense, and the parts of Maryland with more Republicans (the Eastern Shore and the western panhandle) are placed in districts more likely to reflect their local politics. The Princeton Gerrymandering Project gave the commission's map an "A" grade.

By rejecting that proposal and "adopting a new map that was even more blatantly political" than the previous map, "the Maryland Legislature virtually dared the courts to do anything about it," Walter Olson, a member of the citizens' commission and a senior fellow at the Cato Institute, tells Reason.

Courts are increasingly taking that dare in other states too. State judges in Pennsylvania and North Carolina have recently tossed out Republican-drawn maps for being too politically slanted.

As those cases and the current situation in Maryland make clear, both parties seek to put their thumbs on the scale of congressional elections by trying to use redistricting to let politicians select their voters rather than the other way around. But Maryland's highly gerrymandered map has also exposed how support for redistricting reform is often warped for partisan purposes too.

As I wrote in December, Rep. Jamie Raskin (D–Md.) has been one of the loudest voices in Congress calling out Republican attempts at gerrymandering. He's claimed on Twitter that "gerrymandering empowers political minorities to redistrict political majorities into near-oblivion," issued an official statement claiming that "Republican state legislators…have perfected the art of redistricting for the goal of destroying the political opposition," and was one of several members of Congress to submit an amicus brief to the U.S. Supreme Court calling for it to "end partisan gerrymandering" when the Court reviewed Wisconsin's GOP-drawn gerrymander last year.

But Raskin's district in Maryland is highly gerrymandered and would have gotten even more misshapen if the new map had survived Battaglia's review. Raskin has refused to comment on the map-drawing process in his home state—a place where his supposedly reform-minded principles would likely have more influence, if he chose to exert it, than would his performative outrage on Twitter or in front of the Supreme Court.

At the same time, the obviously superior maps drawn by Maryland's citizens' commission suggest there is a way forward for those actually interested in reforming redistricting. It's impossible to remove politics from the process entirely, of course, but anything is probably better than letting sitting legislators from a single party control the mapmaking process.

The defeat of Maryland's highly partisan congressional map is a terrific real-world example of how greater use of statistical analyses and greater involvement of the general public can defeat the incumbency-protection scheme that is gerrymandering—or at least lessen the damage it does.

Show Comments (52)