Weather Is Not Climate. Or Is It?

For years, experts warned that any given hurricane or heat wave cannot be attributed to long-term changes in average temperatures. But it turns out that climatologists and meteorologists sometimes can establish such causal relationships.

News outlets have long cited extreme weather events as examples of how greenhouse gas emissions affect the climate. In response, experts typically would emphasize the distinction between weather and climate, warning that any given hurricane or heat wave cannot be attributed to long-term changes in average temperatures. But it turns out that climatologists and meteorologists sometimes can establish such causal relationships.

"First of all, it's important to highlight that every climate extreme weather event has multiple causes," Friederike Otto, an Oxford University climate researcher associated with the World Weather Attribution (WWA) collaboration, told MIT Technology Review in 2020. "So the question of the role of climate change will never be a yes or no question. It will always be, 'Did climate change make it more likely or less likely, or did climate change not play a role?'"

For the last decade or so, climate researchers like Otto have been working on statistical techniques aimed at estimating the extent to which a warmer world is making weather events more extreme and/or increasing the frequency of such events. One technique is to run climate models using the current levels of atmospheric greenhouse gases to see if they reproduce the relevant observed weather trends for a region. If the models accurately track the actual record of weather events, the researchers next run them assuming pre-industrial greenhouse gas concentrations. The differences in, say, the maximum temperature during a heat wave, the amount of rainfall dumped by a hurricane, or the timing and extent of wildfires provide an estimate of how much man-made warming may contribute to specific extreme events.

Consider the massive heat wave in June 2021 that produced record-breaking temperatures in the Pacific Northwest, including highs of 116 degrees Fahrenheit in Portland, Oregon; 108 degrees in Seattle, Washington; and 121 degrees in Lytton, British Columbia. Under pre-industrial conditions, WWA researchers found, the chance of a heat wave like that was essentially zero. "Western North American extreme heat [was] virtually impossible without human-caused climate change," they concluded.

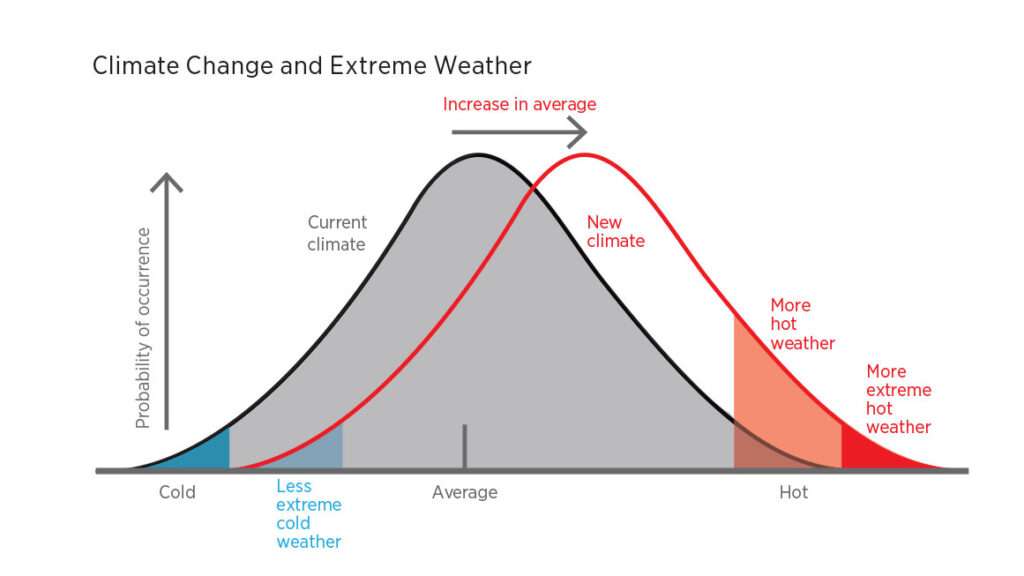

According to the latest comprehensive report on the physical-science basis of man-made climate change from the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), "it is extremely likely that human influence is the main contributor to the observed increase in the intensity and frequency of hot extremes and the observed decrease in the intensity and frequency of cold extremes on the global scale." Given that the average global temperature has risen by around 1.1 degrees Celsius during the last century, it is not too surprising that heat waves have become hotter, lengthier, and more frequent.

Other notable 2021 extreme weather events in the U.S. included Hurricane Ida, which slashed the coast of Louisiana in August; a massive December outbreak of tornadoes in Kentucky; and the Colorado wildfire that destroyed 1,000 houses just outside Boulder in late December. Are all those events also strong examples of weather as climate?

In just six hours before it came ashore, Ida intensified from a Category 1 storm (winds between 74 and 95 miles per hour) to a Category 4 storm (winds between 130 and 156 miles per hour). It dumped between 15 and 20 inches of rain on parts of southeastern Louisiana.

Studies "provide limited evidence of anthropogenic effects on [tropical cyclone] intensifications so far," the IPCC report notes, "but high confidence for increases in [tropical cyclone] heavy precipitation." In other words, the evidence that global warming is causing hurricanes to spin up faster is currently weak, but the evidence that it boosts rainfall during hurricanes is stronger. WWA researchers estimated that global warming likely intensified the rainfall from Hurricane Harvey, which hit Texas in 2017, by 15 percent.

Climate models are too coarse and observational data too sparse to draw firm conclusions about how climate change may be affecting tornadoes. The IPCC report notes that the annual average number of tornadoes in the U.S. has remained constant since the 1970s, although their location appears to be shifting from the Great Plains toward the mid-South, which includes Kentucky.

Fire weather involves a combination of high temperatures, drought, and low humidity. From 1979 to 2013, the global burnable area affected by long fire-weather seasons doubled, and the average length of the fire-weather season increased by 19 percent, according to research cited by the IPCC. Despite climate change "at the global scale," however, "the total burned area has been decreasing between 1998 and 2015 due to human activities" such as agricultural expansion and intensification.

During the final six months of 2021, Colorado's statewide temperatures were four degrees Fahrenheit above average, and it was by far the driest six-month period on record for the Denver area. Yet the National Weather Service had not issued a fire-weather "red flag" warning for the Boulder area on December 30, the day the wildfire broke out, because the relative humidity had not fallen below 15 percent.

In a May 2021 Climatic Change article, Otto and her collaborators observe that extreme event attribution studies have three primary uses: answering questions from the public, providing information on how to adapt to future weather extremes, and, last but not least, "increasing the 'immediacy' of climate change, thereby increasing support for mitigation." Mitigation means policies aimed at drastically cutting the amount of carbon dioxide emitted, largely from burning coal, oil, and natural gas.

"Every time you hear or read a claim about this or that disaster being linked to climate change, as interesting as the underlying science may be, what is actually being conveyed is a stealthy promotional message encouraging you to consider climate change to be important and thus to support efforts to decarbonize the economy," notes University of Colorado political scientist and climate change researcher Roger Pielke Jr. "As important as these messages are, what they leave out are all of those actions that are important for actually reducing the future impacts of extremes, regardless of the particular details of a climate change influence."

Cutting carbon dioxide emissions certainly will play a major role in addressing the problem of man-made climate change, though such a policy will also involve massive tradeoffs affecting human well-being and progress. But as Pielke observes, it is not the only policy that can help humanity cope with deleterious weather changes.

Economic growth and technological innovation already have enabled people to thrive as they adapt to extreme weather events. As a result, noted Copenhagen Consensus Center President Bjorn Lomborg in a 2020 Technological Forecasting and Social Change article, the chance that a person might die from climate-related risks such as floods, droughts, storms, wildfires, and extreme temperatures has fallen by more than 99 percent since 1920.

Attribution research is increasingly able to tell us how climate change is affecting the likelihood of extreme weather events. But it cannot tell us how best to handle them.

Show Comments (454)