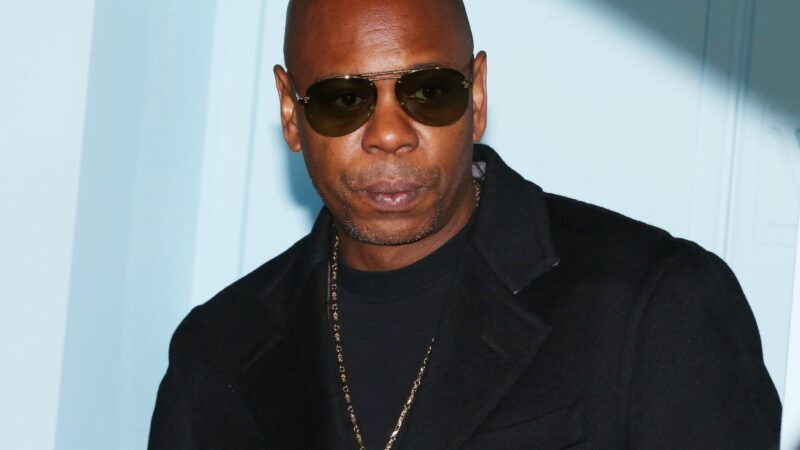

Dave Chappelle Is a NIMBY

The comedian doesn’t want a new subdivision behind his house. Fortunately, he can’t stop it.

Dave Chappelle is literally opposed to new development in his backyard. But private property rights prevent him from doing much more than talking about "not in my backyard" (NIMBY) views.

At a Monday meeting of the Village Council of Yellow Springs, Ohio, the famous comedian joined his fellow residents in speaking out against the plans of local developer Oberer to construct a new neighborhood in the community.

"I'm not bluffing. I will take it all off the table," said Chappelle at the hearing, an apparent threat to pull his planned business investments out of Yellow Springs. The Dayton Daily News, which first reported on the story, says that the comedian has plans to launch a restaurant and comedy club in the town.

Later that evening, the village council failed in a tied 2–2 vote to approve a rezoning ordinance that would have allowed Oberer to move forward with its project; a mix of single-family homes, duplexes, and townhomes totaling 140 units on a 55-acre site recently annexed into Yellow Springs.

That was the outcome Chappelle and other Yellow Springs anti-development activists were hoping for. But it's not going to get them what they want.

While Oberer's proposal for a mix of housing types is dead, it still has every ability to move forward with its initial plan for the property: a single-family subdivision that could add 143 new homes to the village.

There's every indication that Oberer intends to follow through on building a single-family neighborhood. Workers for the company were cutting down trees behind Chappelle's house—which abuts the site of the proposed development—just days after the Monday village council vote, says Yellow Springs Village Manager Josue Salmeron.

The company will still have to get a subdivision plan approved by the village and then obtain building permits for the single-family homes it will now build. But that's all a routine administrative process, says Salmeron. The village has basically no discretion to stop it.

People who had hoped that a village council vote sandbagging Oberer's rezoning request would kill the new subdivision or get the developer to modify its plans were wasting their energies, says Village Council Member Marianne MacQueen.

Opponents "were misinformed and did not understand that the village negotiated as good as we could do," she tells Reason. The rezoning Oberer had requested from the council, she notes, had been the product of over a year of talks between the company and the village.

When Oberer first purchased its Yellow Springs site, it had initially talked about building a new, solely single-family subdivision. MacQueen says that vision didn't mesh well with the village's stated goal of attracting a more diverse set of more affordable housing types to the community.

Shortly after Oberer bought the property, village staff approached the company with the idea of building a neighborhood with a mix of housing types. After some initial trepidation, the company proved receptive to the idea of working out a planned unit development (PUD) agreement with the village.

Eventually, Oberer and Yellow Springs hashed out a plan for a neighborhood featuring 64 single-family homes, 52 duplex units, and 24 townhome units. The latter two types of units would sell for about $100,000 less than the single-family homes, says Salmeron.

Oberer also agreed to build a public park and donate 1.75 acres to the village to be used as the site of a future income-restricted housing development. Village documents suggest that 20 or more units could end up on that site.

It's not necessarily ideal from a libertarian perspective that the local government would have so much input into Oberer's project. Indeed, the developer and village staff negotiated on everything from homeowners association rules in the new development to the angle of outdoor lighting fixtures.

Still, the company always had the option of pressing ahead with its original single-family development plan, so the PUD seems voluntary enough. (Oberer didn't respond to Reason's request for comment.)

In order to legalize those planned duplexes and townhomes, the village council needed to vote on a rezoning of Oberer's property from its existing single-family residential zoning to higher-density residential zoning.

That process brought out a lot of opposition to Oberer's planned development, including from Chappelle.

"I just want to say I am adamantly opposed to it," he said at a December hearing, reports WHIO TV 7. "I have invested millions of dollars in town. If you push this thing through, what I'm investing in is no longer applicable."

MacQueen separates opposition to the Oberer development into three factions.

The majority of opponents, she says, wanted the city to renegotiate a different PUD agreement with more affordable housing, better environmental protections, and other public benefits. Another smaller group preferred having an exclusively single-family development.

A third faction, which MacQueen says included Chappelle, was generally opposed to development on the site. "They felt that if they defeated the PUD they could find ways to continue to put roadblocks in the way of the developer," she says.

MacQueen says she, like the majority of opponents, would also have preferred a PUD with more affordable housing. But the city has no leverage to compel Oberer to agree to something like that. Stopping development outright wasn't going to happen either, given that Oberer's property was already zoned for single-family housing.

"[Oberer] bought the property. They have the right to do that. It doesn't have to come to council. It's not something that we'd vote on. It's by-right," she tells Reason.

At Monday's meeting, village staff said that any effort to rezone Oberer's property to stop development without the company's consent would see the village hit with a lawsuit it would almost certainly lose.

Chappelle, in his brief public comment, suggested that the city should be more worried about him withdrawing his investment from the village than a lawsuit from Oberer.

"Why the village council would be afraid of litigation from a $24 million company while it kicks out a 65 million-a-year company," he said. "I cannot believe you would make me audition for you. You look like clowns."

That warning seemed to be enough to kill the PUD. Whether it will goad the village into taking further action to stop Oberer's development isn't clear. (Council members who voted against the PUD didn't return Reason's request for comment.)

It's not obvious that the village has either the legal ability or political will to stop the developer from moving ahead. As mentioned, the company is already at work clearing its property to make way for new homes.

That detail distinguishes the Yellow Springs episode from many other development spats around the country.

Whether it's rural Ohio or downtown San Francisco, plans for new housing often spark local opposition from residents who worry about the impacts new homes will have on traffic, property values, or sunlight.

The difference is that in San Francisco, the law gives politicians and NIMBY neighbors boundless opportunities to stop or delay the approval of new housing. Its elected officials have near unchecked discretion to deny even totally zone-compliant projects. Individual citizens or special interest groups can also gum up the works with cynical environmental lawsuits.

As a result, the city builds much less housing than it could, and what does get built takes much longer than it should. San Francisco is one of the worst offenders in this regard, but it's hardly the only city that makes development painstakingly difficult. Hostility to new housing is the primary reason that these cities have become so unaffordable.

While Yellow Springs is a small community, its growing popularity is also putting upward pressure on home prices and rents.

Oberer's plans for dozens of new homes in the village will help suppress those rising housing costs. That's a good thing, and there's not a lot that angry residents (even famous ones) can do about it.

Rent Free is a weekly newsletter from Christian Britschgi on urbanism and the fight for less regulation, more housing, more property rights, and more freedom in America's cities.

Show Comments (125)