The Supreme Court's Alabama Redistricting Ruling Looks Like a Holding Pattern, Not a Power Grab

Contrary to some of the more breathless reactions, it doesn't suggest a conspiracy to help Republicans win elections by disenfranchising black voters.

The Supreme Court on Monday waded once more into the high-stakes battle over congressional redistricting—but the decision doesn't seem to be the partisan power grab that it is being portrayed as.

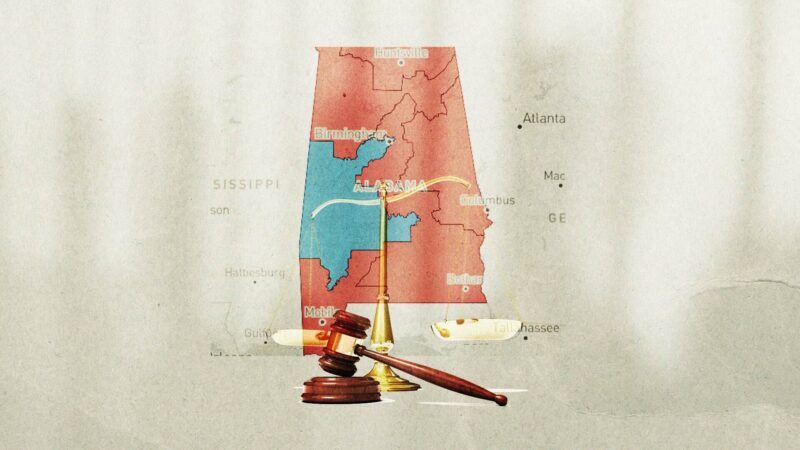

In a 5–4 ruling, the justices issued a temporary stay that blocked a lower federal court from ordering Alabama to redraw its new congressional districts on the grounds that the map disadvantaged minority voters. Though the Supreme Court indicated it is willing to consider the case on the merits at a later time, the immediate outcome of Monday's order is that Alabama's districts are likely to be used, as drawn by state legislators, in this year's midterm elections.

With five of the high court's six Republican-appointed justices in the majority (Chief Justice John Roberts was the lone exception), the ruling immediately set off a firestorm of criticism from court watchers who believe the conservative jurists are trying to stack the deck for Republicans. "This is another major blow to the Voting Rights Act that will likely preserve Alabama's current racist gerrymander," wrote a breathless Mark Joseph Stern, staff writer for Slate, on Twitter. Later, he called the ruling "catastrophic" and claimed that "it is hard to overstate how lawless the Supreme Court's order is." "Black Alabama voters just got screwed by the Supreme Court," is how CNN framed a segment on the decision. And there's nothing subtle about how most media outlets covered the story as a political win for Republicans.

Maybe that's all true, but it's hard to see how the text of the actual decision supports some of those overheated takes. There are at least two good reasons to not overreact to this decision.

First, this is likely not the Supreme Court's final say in the matter. In fact, justices on both sides of Monday's ruling indicated they'd like to take a closer look at Alabama's districts and the competing claims about whether the state should have two majority-minority districts, as the lower federal court had determined.

As is usual with simple orders like this, there was no majority opinion released by the court. But Justice Brett Kavanaugh authored a concurring opinion to explain why the majority voted to issue the stay on the lower court ruling. Importantly, he leaves the door very much open to a full review. "The stay order does not make or signal any change to voting rights law," he wrote. "The stay order is not a ruling on the merits, but instead simply stays the District Court's injunction pending a ruling on the merits." (Emphasis in the original.)

The issue, from Kavanaugh's perspective, is all about timing. There is an established precedent that federal courts ought not to intervene in state election disputes immediately before an election, he notes. Alabama's congressional primary elections are scheduled for May 24, but candidates are due to begin filing petitions to get on the ballot next month. That means there's not enough time for the Supreme Court to have a hearing on the merits and for new district maps to be drawn (if they are deemed necessary) afterward.

Without adequate time for a full review, the high court is effectively left to balance two competing sets of harms. On one hand, there is the potential harm that comes from holding an election with district lines that unfairly disadvantage black voters in Alabama. On the other, there's the potential harm of leaving candidates, voters, and state officials with an unclear idea of what the district lines actually are in the months leading up to the election.

Certainly, neither is an ideal situation. And allegations of racial gerrymandering ought to be taken seriously—a key part of the Voting Rights Act is specifically meant to prevent states from drawing districts to disenfranchise black voters, as voting rights advocates say Alabama has done.

But the case against Alabama's new districts is hardly clear-cut. On the map approved by state lawmakers, there would be six likely Republican districts and one majority-black, likely Democratic district. What you think about that split probably depends on your own political leanings, but the operative question in the federal lawsuit is whether state lawmakers in Alabama (a state where about 27 percent of the population is black) should be required by federal courts to draw a second majority-minority district.

Advocates for that outcome have a good point about how the 7th district is "packed" with black voters—it includes Birmingham and much of the state's rural "Black Belt"—in such a way that might dilute the black vote in other districts. But the best argument against a forced redrawing of districts is that Alabama's new map looks almost identical to the one that was in place from 2011 through last year. And, for that matter, it's nearly identical to the one used for the decade before that too.

Certainly, it's possible that the longstanding status quo of a single majority-minority district is a racist gerrymander—or that it violates the Voting Rights Act. But that's not obvious.

"The Voting Rights Act claim against Alabama was not that strong," Andy Craig, a staff writer who covers voting rights and election issues for the libertarian Cato Institute, tells Reason. "It's theoretically possible to draw a second majority-black district, but just barely and only at the extreme expense of other traditional criteria like compactness."

These are the same tricky questions—what matters more, the race of voters or the compactness of a district—that are poorly suited to courtrooms even when there is time for a full hearing of the issues.

Regardless, it was not, as some coverage of the case has suggested, Republican state lawmakers who took radical action here. It was the federal district court, which on the eve of an election overturned a map that is not materially different from the maps that have been used in every congressional election for the past few cycles. Were those maps racially discriminatory too? If so, why weren't they challenged?

Again, it's definitely possible that the federal district court is correct. And it's definitely possible that a full hearing by the Supreme Court on the merits of the case will confirm that.

But, for now, the Supreme Court was in a difficult spot. By not issuing a stay of the lower court ruling on Monday, the justices would have been signaling that federal courts everywhere were free to substitute their own judgment for that of the legitimate redistricting authorities in the states before this year's midterms. That's the second reason why the Supreme Court likely voted the way it did in this case.

And that skepticism of substituting federal judicial authority for state authority in redistricting cases is well established in Supreme Court precedent. In its most recent major ruling on gerrymandering, the court ultimately decided that there was limited scope for federal courts in these disputes. "Excessive partisanship in districting leads to results that reasonably seem unjust," Roberts wrote in 2019. But that, he added, "does not mean that the solution lies with the federal judiciary." Even though the Voting Rights Act does give federal judges greater jurisdiction over claims of racial gerrymandering, Monday's stay is not a radical departure from the court's history of deferring to state lawmakers as the legitimate (if often self-serving) authority in drawing districts.

Indeed, this is exactly what Stern and others who decried Monday's ruling should want. Imagine what would happen if supposedly partisan, Republican-favoring federal judges were empowered to substitute their own judgment about what congressional districts should look like.

I suppose it's possible that all of this is a smoke screen. If you want to believe that the Supreme Court is chiefly concerned with throwing elections to Republicans, then maybe you can convince yourself that Kavanaugh's concern about the timing of the Alabama primary election is a convenient excuse and that the Supreme Court's decadeslong skepticism about wading into gerrymandering issues was a clever ploy meant to provide cover to the GOP in exactly this situation—just so Republicans can win six congressional seats in Alabama this year instead of five. Yeah, maybe that's the grand plan.

Or maybe we should take the justices at their word and wait to see what happens when the Supreme Court revisits this topic in more detail—something that both Kavanaugh and Roberts, in his dissenting opinion, said it likely would—before hyperventilating about the "lawless" court.

Show Comments (39)