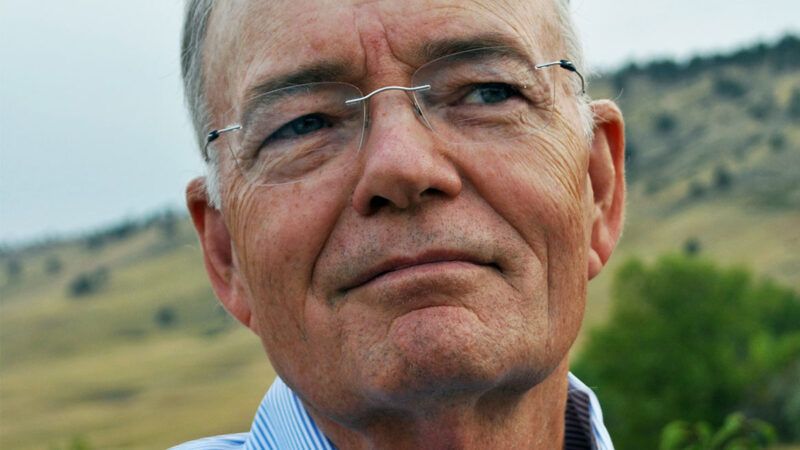

Eugene Huskey on the Soviet Legacy in Central Asia

"This is the nature of an authoritarian regime. You don't quite know where the boundaries of acceptable discourse are. Everything is uncertain."

In 1979, Eugene Huskey was a graduate student at the London School of Economics when he landed the opportunity to spend a year at Moscow State University studying the Soviet legal system. By the time he departed, the Soviet Union had invaded Afghanistan and the United States had announced a boycott of the 1980 Summer Olympics.

In the late '80s, Huskey was invited by the renowned Sovietologist Jerry F. Hough to join a team of American scholars studying the Soviet Republics as the USSR began to unwind under General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev. After the Soviet Union disbanded, Huskey was among the first Western academics in modern history to visit what is now known as Kyrgyzstan and meet with members of its government.

A professor emeritus of political science at Stetson University in DeLand, Florida, Huskey is the author of 2018's Encounters at the Edge of the Muslim World: A Political Memoir of Kyrgyzstan (Rowman & Littlefield). He spoke to Reason's Mike Riggs in September about studying in Soviet Moscow and the politics of Central Asia after communism.

Q: Did you ever feel in danger while studying in the USSR?

A: No. In fact, quite the opposite. I had been there three times before 1979. I might be on the street at 3 a.m.—not very often, but occasionally—and I felt completely safe.

The people who tried to teach me fear were Soviets. I remember one young woman, who was a psychologist and the daughter of a famous scientist there, came into our dorm room at Moscow University and immediately turned on the water, took a pencil and stuck it in our telephone, and turned on music in the background.

Q: I'm guessing that whatever conversation you had with her probably seemed pretty anodyne.

A: This is the nature of an authoritarian regime. You don't quite know where the boundaries of acceptable discourse are. Everything is uncertain. In the Stalin era, you were worried that anything could be used against you. It was obviously much more open when I was there in the height of the [General Secretary Leonid] Brezhnev period, but there were still boundaries that people really didn't know whether they were crossing or not.

Q: When you first visited independent Kyrgyzstan, what awareness did the leaders there have of concepts like negative rights and civil liberties?

A: Very, very few people had any understanding at all of the kinds of concepts that you're mentioning. Their tradition was in dialectical materialism and the history of the working class. They were from the Soviet Union's higher party schools.

Q: Was it exciting for them to hear about these concepts?

A: I think many of them found it disorienting. And if you come forward and advocate the idea of fair play, economic competition, political competition, hiring with no favoritism and no cronies—all that is so deeply ensconced in the system that the ideas we're talking about are a threat.

Q: What are the obstacles to fair play?

A: In places like Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and even Azerbaijan, what you have is a family empire where sons, brothers, sometimes cousins are given key positions in government and access to rents, as the economists call them—you know, unfair profits. It's very difficult for people to compete with that. In fact, you really can't.

Q: How do heads of state hold power in the post-communist world?

A: They rely on this sort of cult that they've created; they rely on the legitimated devices of courts, elections, and a constitution; but they also rely on a network of elites who are in a kind of pyramid, with the leader at the top. Either through jobs, or rents, or something else, they're part of a dense network that is loyal to the leader in part because they're financially better off.

There's an exchange relationship that's taking place that's extremely important, and central, it seems to me, to the stability of these regimes. But that means they've got to work at getting their people elected in the right numbers and making it seem somewhat legitimate, and they've got to constantly be dealing with this really immense client network to make sure that they're on board and that those relationships are stable.

This interview has been condensed and edited for style and clarity.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

"This is the nature of an authoritarian regime. You don't quite know where the boundaries of acceptable discourse are. Everything is uncertain."

Sounds familiar.

Hi) My name is Paula, I'm 24 years old) Beginning SEX model) Please rate my photos at - http://xurl.es/id253925

money generating way, the best way of 2021 to earns even more than $15,000 every month online. start receiving more than $15k from this easy online job. i joined this 3 months ago and in my first month i made $12749 simply doing work for 2 hrs a in day. join this right now by follow instructions mentioned on this web.

===>>............ Visit Here

Disagree. School boards should be protected from critical comments regarding their teaching of critical racism theory. Some parents even have the audacity to show up in person at school board meetings to speak up about these things. A state security force should be used to stop this from happening in the future. They should be persecuted with extreme prejudice.

A few insurrectionists are now attending public events, where only approved speech should be used, and encourage citizens that otherwise have good standing in the party to shout horrific chants such as, “Let’s Go Brandon!” The worst gulag is too good for these monsters.

How can you teach critical race theory without critical comments?

This year do not worry about money you can start a new Business and do an online job I have started a new Business and I am making over $84, 8254 per month I was started with 25 persons company DVx now I have make a company of 200 peoples you can start a Business with a company of 10 to 50 peoples or join an online job.

For more info Open on this web Site............Pays24

> You don't quite know where the boundaries of acceptable discourse are. Everything is uncertain.

Kinda wrong. I’ve graduated from the Moscow State University in 1979, exactly. Boundaries were quite clear: you can TALK - in private, like your dorm - of everything you want. Consequences started at anti-government ACTIONS, including public talk. So this girl:

> one young woman, who was a psychologist and the daughter of a famous scientist there, came into our dorm room at Moscow University and immediately turned on the water, took a pencil and stuck it in our telephone, and turned on music in the background.

- this girl was bonkers. The dorm was basically a free speech zone. Nobody cared. Let me tell you this story.

The beginning of the 2nd year, autumn. Socialism means shortages. Food shortages, product shortages, work force shortages. Not enough “hands” to pickup potatoes. So math students, like all other 2nd year MSU students were spending a month picking potatoes. The middle of nowhere, 100 km west of Moscow. Meaning - jammers jamming Voice of America and other Russian language “enemy stations” were absent. But Voice of America, BBC and others were nice and clear. I had a nice shortwave radio and was listening regularly.

We had two grad students placed to supervise us. One - the executive “officer”, the Komandir. Other - the political “officer”, the Komissar. The Komissar saw his main task as to entertain us. So, he comes to me one day and says: “Mike, why are you listening to BBC? I mean - why are you listening to it ALONE? Please, take your radio to the communal hall each morning and let everyone listen to BBC, we’re off the news here”. And so I was bringing my radio with me each morning and 100 people were listening to Voice of America and BBC - by the request of the Komissar.

So that girl, switching the water on - in the dorm of the MSU in 1979! - to talk to an American was complete bonkers. That, or she was a KGB informer trying to convince him she was not one, lol.

But does the Kyrgyzstan media protect the current ruling peoples the way MSM in American protects the Democratic Party, particularly President Biden?

The DNC and the K... powers have much to teach each other.

"In places like Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and even Azerbaijan, what you have is a family empire where sons, brothers, sometimes cousins are given key positions in government and access to rents, as the economists call them—you know, unfair profits. It's very difficult for people to compete with that. In fact, you really can't."

To be fair, this is the way humans have operated for millennia--in fact, even pre-human apes (and many other mammals) do this.

I think our comments should shake hands.

But...doesn't that describe all of politics, everywhere that politics exist?

If to compare the Kyrgyz fair sex with other nations, they acquired a real independence and felt themselves confident, self-sufficient, and successful not so long ago. Today the majority of these women takes maximum from the possibilities they are offered by the society to achieve success in the profession, in business, and in art. The freedom that the Kyrgyzstan women received encouraged their womanish and enigmatic appearance’s self-realization.

Подробнее: http://beauty-around.com/en/tops/item/980-most-beautiful-kyrgyz-women

This is a really good point. Lots of institutions-in-name can be used to legitimize crooks. The benefit of such institutions isn't in their name but in their actual effects: an unenforced constitution is worthless, a court legislating is worthless, a compromised election is worthless. And, as Professor Huskey indicates, even such worthless institutions can confer apparent legitimacy on corrupt heads of state in troubled nations.

Make your institutions work, before you rely on them in any way as a basis for legitimacy. Challenge the strongman when he steals an election. Denigrate his toadies on the courts when they make up rulings to protect him. Pursue truth, because these hardly-post-Soviet assholes are not going to.