Lockdowns' High Costs and Murky Benefits

Cato economist Ryan Bourne's new book is a much-needed rejoinder to the obtuse economic reasoning of many pandemic-era policy makers.

"We're not going to put a dollar figure on human life," Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat who was then New York's governor, declared four days after he imposed a statewide COVID-19 lockdown last year. The goal, he explained, was to "save lives, period, whatever it costs."

Ryan Bourne's Economics in One Virus offers a much-needed rejoinder to that morally obtuse position. Bourne, an economist at the Cato Institute, highlights considerations that politicians like Cuomo too often ignored as they decided how to deal with a public health crisis more serious than any the country had faced since the influenza pandemic of 1918. Eschewing unwarranted confidence, Bourne takes no firm position on the cost-effectiveness of mass business closures or stay-at-home orders. But he does insist, pace Cuomo, that cost-effectiveness matters, and he deftly shows how economic reasoning illuminates such issues.

If legislators were determined to "save lives, period, whatever it costs," they would set the speed limit at 5 miles per hour, or perhaps ban automobiles altogether, which would prevent nearly 40,000 traffic-related deaths every year. Those policies seem reasonable only if you ignore the countervailing costs. In public policy, economist Thomas Sowell famously observed, there are no solutions; there are only tradeoffs.

"Logically," Bourne writes, "there must be some negative consequences of government lockdowns, and some point at which they might become self-defeating." To figure out when that might be, policy makers needed to estimate the public health payoff from lockdowns and compare it to the harm they caused.

Contrary to Cuomo's framing of the issue, this is not a matter of weighing "the economic cost" of maintaining lockdowns against "the human cost" of lifting them, as if those categories were mutually exclusive. Even in life-and-death terms, lockdowns had a downside, since they plausibly contributed to a spike in drug-related deaths, discouraged potentially lifesaving medical care, and inflicted financial and psychological distress, neither of which is good for your health. And as Bourne emphasizes, "economic welfare" goes beyond household finances or GDP, encompassing everything people value.

Bourne reviews the literature on the benefits of lockdowns, making several important analytical points. If we want to know whether lockdowns "worked," for example, we need to distinguish between the impact of government-imposed restrictions and the impact of voluntary precautions. An early, highly influential projection by researchers at Imperial College London, which was amplified by the Trump administration, envisioned as many as 2.2 million COVID-19 deaths in the United States based on a counterfactual scenario where "we do nothing." But doing nothing was never a realistic option; by then, people already were responding to the pandemic by changing their behavior.

In addition to all the voluntary cancellations of large gatherings such as conventions and sporting events, smartphone mobility data show that individual excursions fell sharply in early March, weeks before most of the lockdowns. One study that Bourne cites, by economists Christopher Cronin and William Evans, estimated that "non-regulatory responses by individuals and businesses" accounted for "between 74 and 83 percent" of the drop in visits to retailers, entertainment venues, hotels, restaurants, and service businesses. Economists Austan Goolsbee and Chad Syverson found that "legal restrictions" were responsible for less than 12 percent of the decline in "overall consumer traffic."

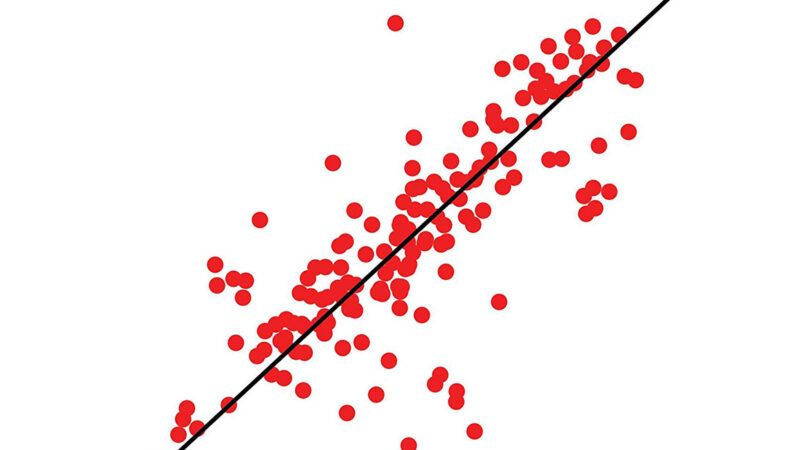

Since "extensive social distancing was happening prior to government orders," Bourne writes, "it would be wrong to suggest all lives saved compared to 'doing nothing' can be attributed to government policies." He suggests that voluntary adaptation "might explain why cases and deaths across countries implementing very different public health interventions nevertheless followed fairly consistent patterns through much of the spring and summer of 2020."

The importance of private precautions cuts both ways in assessing the cost-effectiveness of lockdowns. It reduces the benefits of such policies, but it also reduces their costs. Since Americans spooked by COVID-19 responded by staying at home more and spending less time and money at brick-and-mortar businesses, those businesses and their employees would have suffered (although not as much) even if states had not restricted their operations or shut them down completely. "It is clear that businesses and much economic activity were shuttering or constrained through changed private behaviors," Bourne notes, "even prior to state-government-mandated business closures and stay-at-home orders."

A proper analysis of lockdowns also has to distinguish between COVID-19 deaths that were prevented and COVID-19 deaths that were merely delayed. While conventional wisdom suggests that lockdowns were most effective at reducing virus transmission early in the pandemic, their impact on mortality was at least potentially bigger later on, when better treatment and vaccines were already available or around the corner. Then again, relatively strict states such as California, which experienced the same winter surge in cases and deaths as states that were frequently criticized as lax, did not see any obvious public health benefit from reimposing restrictions in late 2020.

A couple of natural experiments indicated that lifting lockdowns did not have anything like the disastrous impact that critics predicted. After the Wisconsin Supreme Court overturned that state's lockdown in May 2020, economist Dhaval Dave and his colleagues found, the decision "had little impact on social distancing," and there was "no evidence" one month later that it "impacted COVID-19 growth." (Wisconsin, like the rest of the country, did see a modest increase in new cases later that summer, followed by a surge in the fall and winter.) And while Texas Gov. Greg Abbott, a Republican, was widely condemned for lifting business occupancy limits and a statewide face mask mandate in early March 2021, Dave et al. likewise found "no evidence" that the reopening affected cases or deaths.

Here, too, the lesson is not obvious. As Dave pointed out, removing legal restrictions may have had a smaller impact than imposing them if people tended to stick with cautious habits they adopted during lockdowns.

Several studies that Bourne discusses estimate that U.S. lockdowns had a substantial additional effect on cases and deaths, beyond what was already being accomplished through voluntary changes. Here is how he summarizes a study by a team of Penn-Wharton economists: "Although the private responses did most of the heavy lifting, the combined impact of state stay-at-home orders, school closings, and nonessential business closures across the United States reduced deaths by 48,000 in the first three months of the pandemic." By contrast, a subsequent study by researchers at the University of Chicago, published after Bourne's book, concluded that lockdowns during that period "did not produce large health benefits but also accounted for a small share of pandemic-related economic disruptions."

Assuming that estimates of large effects are credible, there is still the issue of what price was worth paying to avoid those deaths. Cuomo, who asserted that "a human life is priceless" even as he pursued a reckless nursing home policy that probably caused many avoidable deaths, thought even asking that question was a moral affront. But in a world of finite resources where officials routinely and appropriately weigh the cost of lifesaving regulations, the question is unavoidable.

Regulators commonly assume a policy is justified if it costs around $10 million for each death it is expected to prevent. That "value of a statistical life" (VSL) is derived from research on how much extra pay people demand for hazardous work, which involves a relatively young and healthy population. As Bourne notes, this VSL implies that "we should be willing to effectively sacrifice up to 10 percent of all U.S. wealth" (which is roughly five times America's GDP) to "save the lives of just 0.33 percent of the population." But given the age distribution of COVID-19 deaths, which were overwhelmingly concentrated among elderly people with preexisting health conditions, some economists think the VSL in this context should be closer to $3 million, which obviously would make a big difference in estimating the impact of lockdowns.

Fully considered, Bourne thinks, both the costs and the benefits of lockdowns may have run into the trillions of dollars. Even if the latter sum was higher, that does not necessarily mean lockdowns were the best approach, since less sweeping, more carefully targeted policies might have achieved similar results at a lower cost, as several international surveys of COVID-19 control measures have suggested. Bourne does not venture a definitive conclusion.

In addition to considering the merits of lockdowns, Bourne uses the pandemic to illustrate economic concepts such as externalities (the justification for government intervention in this case), marginal analysis (which politicians too rarely applied in judging the wisdom of restricting low-risk activities such as boating and fishing), the price mechanism (which policy makers keen to stamp out "price gouging" tended to ignore), moral hazard (which suggests that some COVID-19 precautions might have counterintuitively encouraged risky behavior), and public choice (which helps explain which businesses got bailouts). Bourne's focus throughout is on smart questions rather than glib answers—an approach frequently missing in the pandemic era's acrimonious debates.

Economics in One Virus: An Introduction to Economic Reasoning Through COVID-19, by Ryan A. Bourne, Cato Institute, 309 pages, $19.95

Show Comments (45)