Texas Court Recommends a New Trial for a Man on Death Row, Saying the Trial Judge's Anti-Jewish Bias Violated Due Process

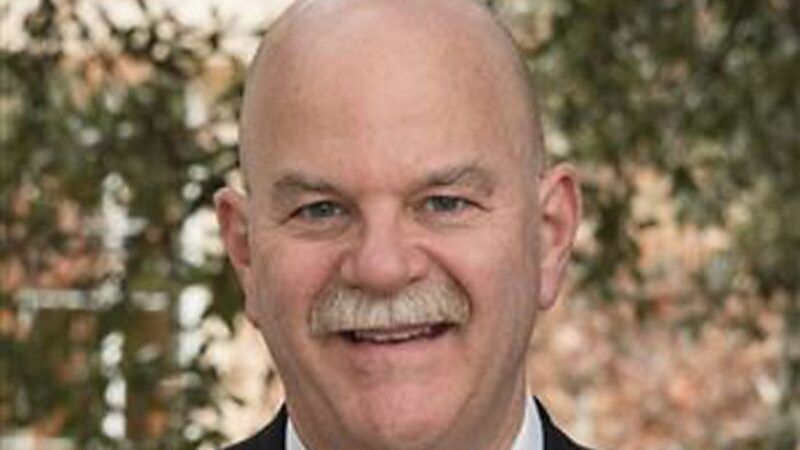

A district court judge found "overwhelming evidence" of Vickers Cunningham's bigotry.

Randy Halprin was one of seven inmates who escaped from a maximum-security Texas prison in December 2000 and then robbed an Oshman's sporting goods store in Irving. The robbers fatally shot Irving police officer Aubrey Hawkins shortly after he arrived at the store. Halprin was sentenced to death in 2003 because of his involvement in the robbery, although he testified that he played a minor role in the crime, did not carry a gun, and fled when the shooting started.

Halprin was scheduled to be executed on October 10, 2019, but the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals granted him a stay after he claimed that the trial judge, Vickers Cunningham, was biased against him. Halprin is Jewish, and he alleged that Cunningham was anti-Semitic. While that might sound like a desperate last-ditch attempt to avoid execution, a Texas judge this week recommended that the appeals court order a new trial for Halprin based on "overwhelming evidence" of Cunningham's bigotry. Dallas County District Court Judge Lela Lawrence Mays concluded that Cunningham's failure to recuse himself, despite his longstanding animus against Jews, violated Halprin's right to due process.

"The facts now before us are extreme by any measure," Mays writes. "On these extreme facts the probability of actual bias rises to an unconstitutional level." Given Cunningham's "extensive history of prejudice and bias," she says, "a new, fair trial is the only remedy."

The evidence cited by Mays comes mainly from testimony by Cunningham's friends and relatives, none of which the state challenged. It paints a picture of a man who was driven by hatred of racial, ethnic, and religious minorities throughout his life. Mays found that the testimony from multiple sources, who corroborated each other on key points, was much more credible than the former judge's denials. "Before, during, and after Halprin's capital murder trial," Mays says, Cunningham, who left the bench in 2005 to run for Dallas district attorney, "harbored deep-seated animus towards non-white and non-Christian people and deep-seated racial, ethnic, and religious prejudices."

Tammy McKinney, a longtime friend who grew up with Cunningham, testified that he referred to Halprin as a "fucking Jew" and a "goddamn kike." Regarding the death sentences imposed on Halprin and the other escaped convicts, she recalled, he said, "From the wetback to the Jew, they knew they were going to die."

The state argued that such epithets were understandable in light of Halprin's crimes. But Cunningham's outrage at Halprin's role in Hawkins' death does not explain a remark about defense attorney Barry Scheck, director of the Innocence Project, that was reported by Amanda Tackett, a friend who worked on Cunningham's unsuccessful district attorney campaign. According to Tackett, Cunningham complained that the "'filthy Jew'…was going to come in and free all these 'niggers.'"

Nor does righteous indignation explain why, again according to Tackett, Cunningham said Jews "needed to be shut down because they controlled all the money and all the power." Or why he demanded that his daughter break up with her Jewish boyfriend, whom he called "that Jew boy," and threatened to stop paying her law school tuition if she failed to do so (according to Tackett and the former boyfriend). Or why Cunningham donned suspenders and a green visor before telling Tackett that he would be her "Jew banker" at a casino-themed party. Or why, according to McKinney, Cunningham said "he wanted to run for office so that he could save Dallas from 'niggers,' 'wetbacks,' Jews, and dirty Catholics."

As some of those examples suggest, the bigotry described by Cunningham's friends and relatives extended beyond Jews. McKinney said Cunningham had been calling his brother "nigger Bill" for as long as she could remember—a detail confirmed by Bill, who said Cunningham had mocked him with that sobriquet "his entire life." On his way to "a campaign event at a charitable foundation run by African Americans," Tackett said, Cunningham joked that he was wearing his "nigger tie." McKinney recalled that Cunningham "said any 'nigger' or 'wetback' walking into his courtroom knew they were going to go down."

As a Dallas prosecutor, Mays notes, "Cunningham intentionally removed all black prospective jurors during jury selection for a 1992 murder trial. [He] acknowledged what he had done, but he defended his strikes by claiming the prospective jurors' Democratic party affiliation, not their race, triggered [his] actions."

In a 2018 interview with The Dallas Morning News, Tackett said Cunningham had complained a few years before about then–Dallas District Attorney Craig Watkins' efforts to exonerate people who were wrongly convicted. "Did you see what nigger Watkins is doing, setting all those niggers free?" she recalled Cunningham saying. "He'll never lose an election because all the niggers want their baby daddy out of jail."

As Mays notes, the Morning News "reported that people close to Cunningham—including his mother, brother, and a former political aide—knew him to be 'a longtime bigot.'" The paper said "the former judge repeatedly use[d] the N-word to insult black people behind their backs" and "described criminal cases involving black people as T.N.D.s," meaning "typical nigger deals."

Cunningham admitted that he had created a living trust for his children that would deny them money if they married anyone who wasn't white or wasn't Christian. But when the Morning News asked him, during a video interview, whether he had ever used the word nigger, "Cunningham paused for nine seconds" and "asked if the question referred to using the word in court." When he was told that the question referred to using the word in any context, he said he had never done so. "This Court, having viewed Cunningham's delay and demeanor, and having considered the uncontested statements of [three witnesses], finds Cunningham's denial is not credible," Mays says.

In defending Halprin's conviction and sentence, the state did not deny any of these allegations against Cunningham. Instead it argued that his anti-Semitism and racism did not amount to a bias that denied Halprin his right to a fair trial.

It is not hard to see how Cunningham's hatred of Jews could have affected the outcome of the trial. Under the Texas "law of parties," the prosecution did not have to prove that Halprin killed Hawkins or intended to do so. But he was eligible for a death sentence only if he "actually caused the death of the deceased," "intended to kill the deceased or another," or "anticipated that a human life would be taken." Halprin's defense hinged on minimizing his role in the robbery.

Halprin wanted to introduce a Texas Department of Criminal Justice "ranking document" that said he "never exhibited leadership qualities," was "very submissive," and was the "weakest" of the escapees. Mays notes that Cunningham "repeatedly rejected Halprin's attempts to introduce the ranking document." She adds that "Judge Cunningham relied on his discretion to deny Halprin's repeated attempts to have his expert witness testify concerning the facts underlying her opinions" and "denied Halprin's requested charge concerning the law of parties."

Mays thinks "one or more of these rulings could have made a difference in the

jury's deliberations." She notes that "jurors deliberated over Halprin's punishment for more than six hours." During the deliberations, they sent a note asking about "the difference between whether Halprin 'anticipated that a human life would be taken' and 'should have anticipated.'"

Mays notes that a judge's bias also can be manifested in more subtle ways that may not be reflected in the official record. She quotes the 5th Circuit's observation that "the record does not reflect the tone of voice of the judge, his facial expressions, or his unspoken attitudes and mannerisms, all of which, as well as his statements and rulings of record, might have adversely influenced the jury and affected its verdict."

While Halprin might have been sentenced to death even with a different judge, Mays says, the Constitution "forbids the participation of a judge in a criminal trial who harbors an actual bias" or presents "an objectively intolerable risk of bias." The Supreme Court's decisions in this area do not hinge on whether a judge's bias actually affected a trial's outcome. "Even if there is no showing of actual bias in the tribunal," Mays writes, "due process is denied by circumstances that create the likelihood or the appearance of bias."

The state argued that Cunningham's privately expressed views about Jews and other minorities were not sufficient to establish unconstitutional bias. "If this Court were to accept the State's argument," Mays says, "it would find that the Constitution forbids a judge from presiding over a case in which he could receive $12.00 if he convicts the defendant"—an example drawn from a 1927 Supreme Court decision—"but permits a judge to preside over a capital case despite the judge thinking of the defendant as a 'goddamn [kike].'"

Halprin is hardly a sympathetic figure. In addition to the crime for which he received a death sentence, he brutally assaulted a toddler in 1996, breaking his arms and legs, fracturing his skull, and beating his face. He was serving a 30-year sentence for that horrifying crime when he escaped from prison. But even the most despicable defendant is entitled to a fair trial, especially in a case where his level of culpability is the difference between life and death.

Show Comments (71)