A Louisiana Prosecutor Escapes Responsibility After Allegedly Covering Up Rape Allegations Against a Prison Official

No accountability for government corruption.

"The allegations in this case are sickening," writes Circuit Judge James C. Ho for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in Lefebure v. D'Aquilla. Ho goes on to detail a scenario that really is nothing short of nauseating: An assistant warden in Louisiana allegedly raped his cousin-in-law repeatedly on prison grounds—and conspired with the local prosecutor to avoid legal consequences.

Even though the state collected convincing evidence of her claims, Priscilla Lefebure cannot bring any suit against District Attorney Samuel D'Aquilla for working to undermine her case and showing special favor to his colleague in the justice system, the 5th Circuit ruled, overturning a lower court decision that would have let part of her suit proceed.

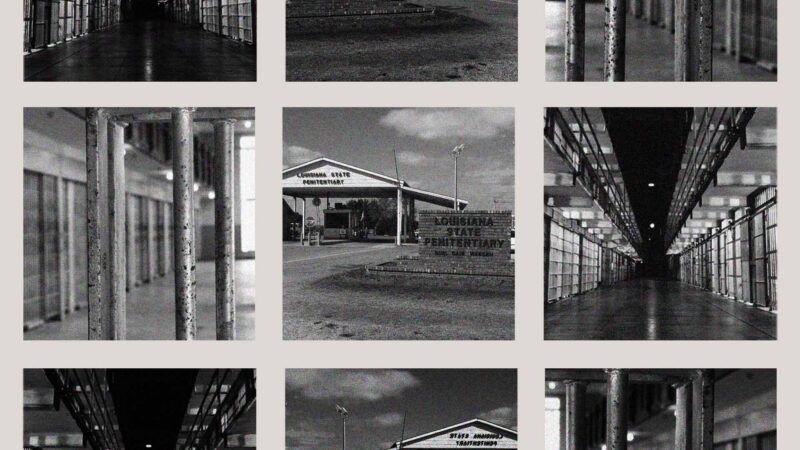

Lefebure found herself in the home of her cousin's husband, Barrett Boeker—then the assistant warden at Louisiana State Penitentiary, also known as Angola—during flooding in Baton Rouge. Lefebure "alleges that Boeker raped and sexually assaulted her on multiple occasions there. First, he raped her in front of a mirror, where he made her watch, while telling her that no one would hear her scream," according to the 5th Circuit's rendering. "Later, he sexually assaulted her with a foreign object, after picking the lock of the room where she was attempting to hide. Afterward, she tried to lock the door again, but he again proceeded to pick the lock and blocked her escape."

A medical exam found bruises, redness, and irritation present on her arms, legs, and cervix, leading to Boeker's eventual arrest for second degree rape.

Yet he was mysteriously never indicted.

Following the arrest, Lefebure claims that District Attorney D'Aquilla "refused to collect and examine the rape kit," "made handwritten notes on the police report highlighting only purported discrepancies in Lefebure's account of the events and presented that report to the grand jury," "declined to meet or speak with her about the alleged assaults before the grand jury proceeding," and "failed to call various witnesses who could have corroborated her version of the events."

It's almost impossible to hold prosecutors accountable for such behaviors, as they are protected by absolute immunity, a legal doctrine that essentially shields them from facing responsibility in civil court for job-related corruption and misconduct. That's not to be confused with qualified immunity, a different legal doctrine that similarly allows certain government officials to violate your rights unless the exact way they did so has been ruled unconstitutional in a prior court ruling. Absolute immunity sets an even higher bar; beneficiaries have a near-free pass at abuse.

But, in a testament to the egregiousness of D'Aquilla's alleged misbehavior, the district court said a portion of Lefebure's claim should move forward. "The Court finds that the DA's alleged conduct in failing to request, obtain, and examine the rape kit; making notes on the police report; and failing to interview the Plaintiff prior to the grand jury hearing were investigative functions for which absolute immunity does not apply," wrote Judge Shelly D. Dick for the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Louisiana. "On the other hand, the alleged failure to call specific witnesses before the grand jury is an advocacy or prosecutorial function for the which the DA is absolutely immune."

Judge Ho—the same judge who said that police officers need to retain qualified immunity "to stop mass shootings"—struck down that idea, instead insisting that D'Aquilla be immune for his investigatory negligence just as he is immune for his prosecutorial negligence. "Lefebure's story is particularly appalling because her alleged perpetrator holds a position of significance in our criminal justice system as an assistant prison warden. We expect law enforcement officials to uphold the law, not to violate it—to protect the innocent, not to victimize them," wrote Ho. "But none of this changes the fact that our court has no jurisdiction to reach her claims against the district attorney, who for whatever reason declined to help her." In a rare move, that elicited a rebuke from three retired federal judges, who asked to file a brief in support of Lefebure. Last week, Ho said they could proceed, although he contends that her suit is doomed.

As for Boeker, he lost his job in May of last year after he was arrested on felony charges—not for the alleged rape, but for assaulting an inmate with a fire extinguisher.

Show Comments (15)