Even COVID-19 Couldn't Kill REAL ID

The ID overhaul, presented as a national security safeguard more than 15 years ago, still hasn't been fully implemented.

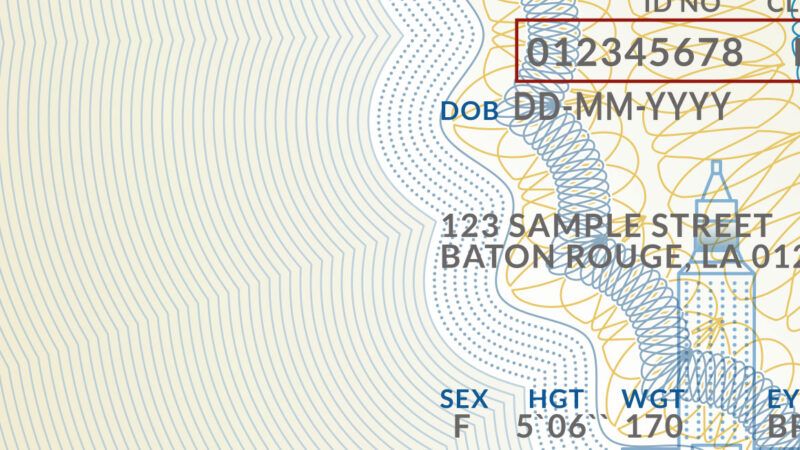

It has been more than 15 years since Congress passed the REAL ID Act. Presented as a national security safeguard, the law requires that American citizens and legal residents have a specific type of identification, incorporating proof of not just their identity but their citizenship, to enter federal buildings or board domestic flights.

Implementation of REAL ID has been a real mess. The National Conference of State Legislatures initially estimated that 245 million government-issued IDs would need to be replaced at a cost of $11 billion. To get these new IDs, applicants have to provide additional proof that they are citizens or lawful U.S. residents.

Unsurprisingly, many states and citizens have resisted these requirements. While compliance was always intended to be phased in, the slow pace of implementation has prompted the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to repeatedly delay REAL ID enforcement. The first deadline, imposed with 120 days' notice, was May 2008. When states missed that deadline, it was extended to December 2009, then May 2011, then January 2013, then October 2020.

The federal government pushed that last deadline back to October 2021 because of the COVID-19 pandemic. States across the country had shut down motor vehicle departments, the main source of state-issued IDs, and told people not to leave their homes unless they had to.

In spring 2021, as travel started picking up, the DHS noted that compliance with the REAL ID program was still quite poor. Only 43 percent of state-issued driver's licenses and ID cards met REAL ID standards. States such as California and Illinois weren't fully compliant with the standards until 2019 and New Jersey and Oklahoma until 2020.

If the DHS actually tried to enforce the law, federal agents would have to turn away huge numbers of air travelers. Recognizing that problem, the DHS announced in April that airports would delay checking passengers for REAL ID compliance until May 2023. Assuming that deadline is not extended yet again, it will have taken 18 years to begin enforcing one of the law's two main provisions.

In the two decades since the September 11 attacks, the absence of REAL ID enforcement has not made domestic flights more vulnerable to terrorism. Meanwhile, the federal government and the states have not been able to implement REAL ID at scale, and the general public does not seem to see a need for it. The next time Congress debates the future of REAL ID, it should repeal the requirement for good.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Ya; It's pretty hard to set any standard of USA citizenship when 22,000,000 people are here as illegal trespassers lobbying for an outright border-less territory invasion.

https://vidjar-review.medium.com/commission-machine-review-automate-all-of-your-affiliate-marketing-in-1-click-e69b01c4936e thanks

Fantastic work-from-home opportunity for everyone… Work for three to eight a day and start getting paid idnsSd the range of 17,000-19,000 dollars a month… Weekly payments Learn More details Good luck…

See……………VISIT HERE

And we should pay more for an ID declaring we are not an illegal alien, while the illegals can get a nearly identical drivers license that’s half the price?

Making extra salary every month from home more than $15k just by doing simple copy and paste like online job. I have received $18635 from this easy home job and now I am a good online earner like others.JUm This job is super easy and its earnings are great. Everybody can now makes extra cash online easily by just follow

The given website…….... VISIT HERE

SCOTUS must end New York State's establishment of pro-abortion dogma.

"A coalition of religious groups in New York has petitioned the Supreme Court for relief from a mandate that requires all employers, regardless of religion or conscience, to cover elective abortions in their health-insurance plans.

The policy, first enacted in 2017 by New York’s Department of Financial Services, is facing a unified legal challenge from a diverse set of religious groups, including Catholic dioceses in New York, several orders of Catholic and Anglican nuns, and a number of Christian churches and charities.

Much like the Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive mandate, which was tacked on to the law by the Health and Human Services Department, New York’s mandate offers only the narrowest of exemptions for most religious employers. Disregarding that most religious groups serve individuals regardless of faith, New York’s Department of Financial Services has extended relief only to institutions that hire and serve individuals of the same religion as the employer."

My body, my choice, your money.

Except for vaccines, of course.

Except for wrongthink.

Except for freedom of religion.

Except for residents that flee high tax Democrat states.

You didn't print that money.

New York’s pro killing of unborn babies policy dovetails with their pro killing of nursing home residents initiatives.

I would never abort my child, but since it's mostly dingers...

Did Biden require background checks of the Taliban using the REAL ID before transferring all that military hardware to them?

"the law requires that American citizens and legal residents have a specific type of identification, incorporating proof of not just their identity but their citizenship, to enter federal buildings or board domestic flights"

Easy answer to the voter id dilemma; if "REAL ID", legal, then make it the standard voting id and done.

Exactly right. There's no reason for any breathing citizen to not have an ID. All states offer them free or at reduced cost to poor people. Almost everybody that wasn't issued a birth certificate in the early 1900s before birth records were required is long dead.

https://www.cato.org/blog/do-voter-id-laws-matter-much

Read and discuss.

Reading is racist.

So is discussion.

In the two decades since the September 11 attacks, the absence of REAL ID enforcement has not made domestic flights more vulnerable to terrorism.

"Of *course* it has! It's just that our brave front-line TSA workers have taken up the slack!"

++ LOL

Real ID is racist.

Oddly, I've noticed nearly everything that makes sense is racist. Imagine that!

Imagine how long it'll take to set up vaccine passports. We'll all probably die of old age by then.

We're already all dead from Kungflu.

They're already set up. Those rather flimsy vaccination cards you get are now basically necessary to do anything where I live (except shop).

Yet it's basically just theater, because anyone can fake them with little effort.

But point this out and you get a horrified reply "But that's illegal!"

Who wants national ID cards and why?

Some on the right, in order to enforce immigration controls and voting access. This is hated by most on the left.

Some on the left, in order to track vaccinations (and soon, other public health program compliance). This is hated by most on the right.

Who brought the popcorn?

Lefties are using the Republican demand for voter/election accountability as a means to implement a national ID card.

Democrats say they are against the idea but they are not. This way they can get their slaves back when they flee high tax democrat states. They can also fully segregate Americans by race or any other superficial factor that lends to Democrats controlling Americans.

Fun fact: My Georgia drivers license has a 30 year expiration date on it. Nice thing they do for veterans in this state.

Plus my passport photo is...lets say not what the federal government wants in a digital photo.

If that is true then GA is dumb af. You're required to get it done every few years to prove you're still capable of piloting a 2 ton machine (and it's a pathetic "test" as is.)

And what would you do then with the ID card? You don't want a national ID card but you DO want voter ID yes? It's gotta be something.

Hell, national ID makes sense anyway instead of using social security numbers, etc. We already have a hodge podge of bullshit- may as well just standardize it.

The only federal ID that makes sense is a passport, since our borders should be secure that anyone who is not an American needs to check in and get authorization to enter the USA.

Otherwise let states have their drivers licenses, voter IDs, or whatever licensing schemes they come up with. You can always move to a state that doesnt do all that big brother stuff. None of those would be mandatory, since you dont have to prove who you are once inside the USA. You dont have to have a drivers license if you never drive.

Main point is to cut state and federal budgets by 50%+ so the states have to decide what to spend their smaller budgets on. Do they want to spend hundreds of millions on IDs or paychecks for their friends in state government?

Most people dont know this but you dont have to have a social security number. Government is trying to make Americans get onto the grid because staying under the radar is relatively easy in America.

You can always move to a state that doesnt do all that big brother stuff. None of those would be mandatory, since you dont have to prove who you are once inside the USA.

Banking, transactions, are off limits if you don't provide ID limiting you to a cash economy. Like it says in a book somewhere... you won't be able to buy or sell without the mark of the beast.

i agreed with you otherwise, make government so small you can drown it in your bathtub.

At least where I live, all they do every few years is check your eyes. Until you are really old, then I think you have to re-test every 5 years or something.

We can generally presume that most people act honestly, and punish the shit out of those who violate our trust (and provide some incentive to others). Or we can presume that most people are dishonest and treat everyone like potential cheats, and require ID and other control checks for everything.

Which society would you prefer?

Which kind I prefer is less germane than the kind I actually live in. And pretending I live in one kind when I actually live in another isn't going to accomplish much.

I have lived in 8 states over the last 25 years and the only time I have taken a written, oral, or practical skills test for driving is when I received my first driver license at the age of 16. Unless you're suggesting my ability to read 2 rows of letters and numbers on an eye chart and provide proof of residency is somehow a reflection of my capability of piloting a 2 ton machine.

LOL stop blaming this on "the lefties" it was a fucking bi-partisan effort. Stop trying to revise and reinvent history. This fucking travesty is a product of both parties just like the Patriot Act.

We already need to show identification for employment, voting access, and many other government functions. The problem is that the existing identifications are easily forged, leading to identity theft and massive fraud.

The last time I voted; I got yelled at for showing my I.D. All they wanted was a power bill.

Real ID: Hard to get.

Fake ID: Easy to get.

'Merica!

Like our news.

Real ID: Easy to get. I went to my local Arizona MVD office (yeah, we don't call it DMV) 3 weeks ago and was in and out with my new Travel ID (yeah, we don't call it Real ID) in less than 10 minutes.

It's a real pain in the ass actually and the directions in Texas were ridiculously vague on what to bring and I had to try twice to get it right.

I moved a few weeks ago. When I went to change the address on my Driver's License, I was asked if I wanted to have my Voter Registration information updated as well? I selected "Yes". Yesterday in the mail I received confirmation of my updated Voter's Info and a Voter ID card. Just throwing it out there. If by registering you get an ID card, what's the problem with having to SHOW IT to vote?

Because not everyone has a driver's license ya dingus. That and REAL ID isn't mandated for anything but entering federal buildings and domestic flights.

So you'd have a big swathe of people who never had any reason to get REAL ID in the first place and were never mandated to.

Seems pretty harmful to democracy to explicitly cut out part of the electorate for not having an ID they were never required to get in the first place.

You dont need an ID to vote. In Georgia, you just have to provide some evidence that you live in the county that you are voting in and you are a US citizen. You can vote provisional and they determine the legality of your vote when they count them.

Birth certificates dont have pictures and neither do utility bills with your address on them.

Lets see, what other arguments do people make? I dont show ID to buy alcohol.

Anyone who says that they cant vote is a liar. Now, whether your vote is counted as legal is a different story.

One reason el presidente Biden lost in Georgia is because tens of thousands of Georgians moved counties and voted in their old county which voids their ballot. We also had thousands of part time residents who tried to vote in multiple states or ex-Georgians who voted in Georgia. Those ballots are void.

Democrats cheat, so its why we are in Civil War 2.0 to resolve these problems once and for all.

I dont show ID to buy alcohol.

Store policies that card until 40 years old have pissed me off for 25 years. Long past looking anything like a 21 year old, I was carded at Buffalo wild wings, circle Ks, and many other fine establishments in multiple states.

I don't show ID to buy alcohol either now, but then again, I left for Central America 8 years ago.

Additionally, you have to register to vote in America. In most states, your vote will not be considered legal if you dont register to vote by a deadline because your voter registration is public record and can be challenged before/after election day.

Since we dont have day-of ONLY voting in America anymore, voter registration is probably the only way to keep voting transparent so we can make sure only US citizens vote and only vote ONCE. Necessary evil.

Entering a public building should never require ID. public buildings are "public".

Real ID isn't exclusive to driver licenses you stupid sack of shit. It also applies to the (free) identification cards that you can get in every state that are merely for identification purposes and do not confer any privilege to drive on public roads.

The number of people who are without the sort of ID that would prove their voting eligibility is so close to zero that the rounding would be wasted. Anyone with a job by definition has the same type of ID that they would need to vote. Anyone on welfare by definition has the same type of ID that they would need to vote. Anyone with a driver license by definition has the same type of ID that they would need to vote. jimc5499 was merely pointing out that you are already mailed a voter registration card when receiving a driver license (the same option is available for those applying for a state-issued photo ID without driving privilege; these are provisions of the "motor-voter" laws you pieces of shit have been using to harvest votes for the last 30 years), yet being asked to display it is somehow an infringement of your rights as a voter. It's an absurdity since the voter registration card is entirely superfluous.

Such an ID is $54 here in WA. Dunno what you're going on about free.

That's fucking hilarious. Washington, a Blue State, charges poor people (and everyone else) $54 for an ID card. Arizona, the Red State I live in, gives them out for free to those 65 and older and those receiving SSI, and just $12 for everyone else. Gotta love them big-hearted Democrats in Washington.

Addendum for WA: "I get public assistance. I cannot afford

a driver’s license. What can I do?

Ask your DSHS caseworker to fill out form 16-

029 'Request for Identicard'. One is at the end

of this publication or ask your caseworker for

the form. Take the completed form to DOL to

get a Washington State Identification card for

five dollars."

But everybody can get a REAL ID.

That's easy to fix: let's make it mandatory.

Will you please stop saying what the government should do? Everyone knows they won't. What do *we* do?!?

Nicely put.

This Real ID hogwash should not have been enacted in the first place.

If only we could focus screening on particular groups most likely to hijack planes…

And right on schedule, the Feds blinked again.

I've been putting this off until I have actually had to use my passport to get on a plane (just like any other third world banana republic hellhole), or until my driver's license needs renewing anyway. So far, I'm still on the winning side of the bet. Looks like I will be for a while longer.

Enjoying a good laugh at the expense of all the sheep who lined up to get theirs earlier. Keep lined up folks, you see the vet next, and I'm told the they keep their blades nice and sharp, and those little cuts they make don't really hurt that much anyway.