Why Welfare Reform Worked

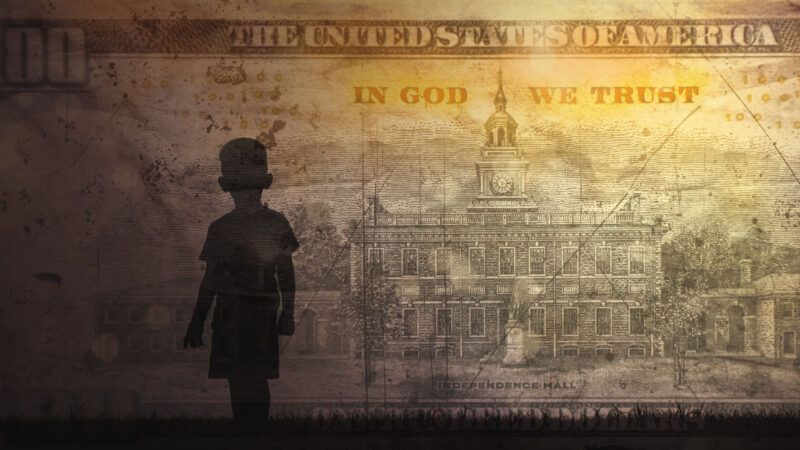

Work, not dependency, was what lifted many people up out of poverty.

In his first State of the Union address in 1993, President Bill Clinton promised to "end welfare as we know it." The system at the time famously disincentivized work by making it more lucrative for many to take benefits instead. He proposed placing time limits on benefits and requiring that recipients "get back to work in private business if possible." Government, Clinton said, could lend a temporary helping hand to those in need. But the time had come to "end welfare as a way of life."

Four years later, Clinton delivered on that promise, signing the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act. The bipartisan legislation transformed the old federal welfare system, known as Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), into a new program, Temporary Aid for Needy Families (TANF).

A decade after signing welfare reform into law, Clinton took a victory lap in The New York Times. "Welfare rolls have dropped substantially, from 12.2 million in 1996 to 4.5 million today," he wrote in 2006. "At the same time, caseloads declined by 54 percent. Sixty percent of mothers who left welfare found work, far surpassing predictions of experts."

Most important, poverty, and especially child poverty, had declined. In 2000, the share of children living in households earning less than the official poverty threshold was 16.2 percent—still too high, but the lowest rate since 1979. The decade after welfare reform passed saw the sharpest drop in child poverty for kids living in homes headed by single mothers since the 1960s.

That improvement was partly a product of the late '90s economic boom. But much of it could be traced to welfare reform legislation, in particular its time limits and its requirement that beneficiaries eventually find a job.

For the most part, those gains have endured. In the last two decades, child poverty rates have fluctuated somewhat with the economy but have generally trended downward. In 2019, the child poverty rate was down to 14.4 percent—and that figure arguably overstates the number of children living in poverty. A separate figure, known as the Supplemental Poverty Measure, put child poverty at 12.5 percent in 2019, down several points from the turn of the 21st century.

As Scott Winship, a poverty researcher at the American Enterprise Institute, noted, the effect was especially pronounced among children of single mothers. Overall, the results suggested that welfare reform was a success.

The lesson was that where government benefits were concerned, work, not dependency, was what really lifted people out of poverty. But a quarter-century after Clinton signed that reform into law, both Democrats and Republicans seem to have forgotten that lesson.

Coronavirus relief legislation already has weakened links between government benefits and work in several ways. Democrats seem poised to weaken those links even further.

Pandemic aid bills that passed with support from both Republicans and Democrats in 2020 included substantial federally funded boosts to state-based unemployment insurance (U.I.). In many cases, beneficiaries could make more by not working and taking benefits than by returning to their old jobs.

The $1.9 trillion American Recovery Plan that Democrats passed in March extended that bonus (albeit at a lower level than last year) through September 2021, even as vaccinations increased and the economy picked up. Employers complained of labor shortages. At the beginning of May, a dismal jobs report showed far fewer jobs created than expected, seemingly confirming that the U.I. boost was causing unemployment. Federal policy disincentivized work, and the result was less of it.

The U.I. bonus was not the only policy that may have created such disincentives. Biden's recovery plan also included an expansion of the child tax credit for most families, converting it into a monthly payment that The New York Times likened to "a guaranteed income for families with children"—with no work requirement. The expansion was initially set for one year, but Biden swiftly proposed extending it through 2025, an implicit bid for permanence.

The program was not technically welfare. But like the program that Clinton reformed, it was pitched as an anti-poverty measure aimed at children. And it represented a return, of sorts, to welfare as we used to know it—in other words, a return to welfare as a way of life.

Show Comments (139)