No Self-Respecting American Should Aspire to Hungarian-Style Nationalism

Extolling the virtues of Viktor Orbán's culture war over a sumptuous meal in Budapest is next-level cognitive dissonance.

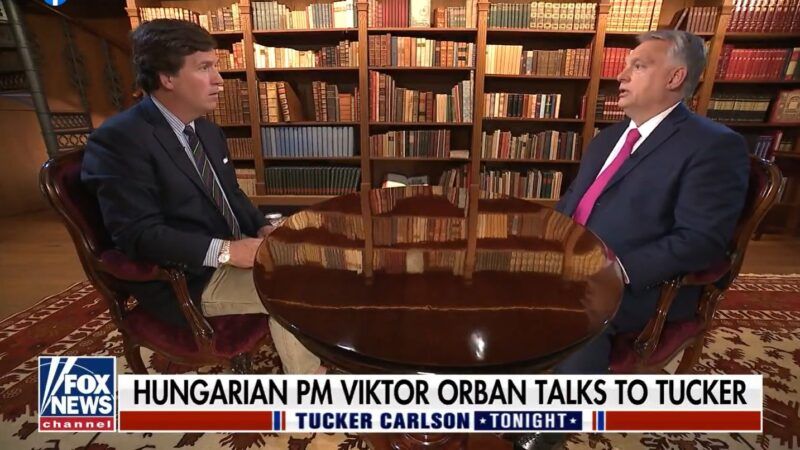

Though much of the great August 2021 debate over the aspirational role Viktor Orbán's Hungary plays in America's still-fermenting National Conservative movement has amounted to a willful misconflation of politics with policy, it's still worth lingering for a moment on Tucker Carlson's fondness for Magyar architecture.

"Here's what I like about the landscape of Hungary, a few Soviet remnants notwithstanding," the top-rated cable news anchor said in a speech Saturday. "It's pretty. It is pretty, the buildings are pretty, the architecture uplifts. So this is another third rail in American politics: You're not allowed to note that our buildings are grotesque and dehumanizing. Why are they bad? Because they are ugly, and ugly dehumanizes us…'dehumanizing' is the act of convincing people that they don't matter, that they're less significant in the larger whole."

Well, about that. Budapest—and the nearby upstream cliffside town of Esztergom, where the Fox News host was delivering his remarks—are indeed lovely to look at, if you don't mind the shabby bits lurking just off-camera in the postcard shots, and otherwise avoid venturing out to the concrete panel housing units that scar all formerly communist metropolises.

But what pleases the foreign eye in the Hungarian capital is often a Potemkin grandeur, the projection of insecure nationalism, the architectural equivalent of fin de siècle bling, dating from that all-too-brief half-century (1867–1914) when Hungary was not just a small-population serial loser of wars, but rather the dual (if junior) monarch of imperial Austria's last Habsburg stand. For a brief window, Budapest got to dress up as Vienna, and boy did it ever.

The city's most celebrated piece of architecture, the Parliament Building (completed in 1904), with its neo-Gothic bones rattling over the Danube, never fails to awe from land or river. Yet inside the structure it's hard to suppress a giggle, once you see the spatial ludicrousness of devoting the world's third-largest legislative building to the unicameral parliament of the planet's 94th largest country. It's like designing the Sistine Chapel to host Wednesday night bingo.

Around the corner is another spectacular colossus I spent too much time in during the mid-1990s, reporting on what would eventually be an ominously illiberal post-communist media law. In that space during the first decade of the 20th century (exact dates vary) opened the Budapest Stock Exchange, then "the largest building of its kind in Europe," and "of a scale far beyond Hungary's requirements." The bourse was liquidated by the state at the bloody end of World War II, and then in 1957, mere months after the Soviet Union put down the October 1956 uprising within Molotov-throwing distance of the palace's magnificent arched entrance, this temple of capitalism was transformed into the imposing headquarters of…communist state television.

It is indeed a gorgeous building, especially now that the audiovisual apparatchiks have decamped. But television journalists from the Land of the Free might pause a breath before whistling too sweetly at nationalist Gargantua that started out as monuments to free enterprise only to be conscripted by the state for purposes of blasting out government propaganda.

The thick roots of 21st century Hungarian nationalism are no mere tangential offshoots from the allure of Orbánism; they anchor the whole enterprise. Though you will usually hear Orbán's GOP fan club enumerate exactly three of the prime minister's tangible accomplishments—he pays Hungarians to reproduce, he limits immigration, he tells Western elites to get bent—the hiding-in-plain-sight attraction to the Fidesz leader is about politics far more than policy. And those politics spring directly from a paranoid sense of historical grievance no self-respecting American should want to experience, let alone emulate.

"Viktor Orbán is winning his culture war," declared the Hungarian's leading American herald, Rod Dreher, in The Spectator last week. "Orbán's Hungary…is an unapologetic beacon of National Conservatism….Hungarians would like to stay Hungarian, without the blights of mass immigration and Heather Has Two Mommies textbooks in kindergarten," enthused ex-National Review columnist John Derbyshire at the "race realist" site VDARE, in a piece Dreher enthusiastically retweeted and then later recanted, maintaining he had no idea that a site named after the first English child born in America may have some off-putting hangups.

"Western elites are terrified that their smear campaign against Hungary will unravel," added a palpably thrilled Frank Furedi at Spiked: "The globalist media have succeeded in establishing a cordon sanitaire around Hungary."

The media have indeed supplied enough hyperbolic fuel to keep a battalion of conservative anti-anti-Orbánists well-fed, grossly mislabeling him a "fascist," a "far-right autocrat," and even "the ultimate twenty-first century dictator." (Xi Jinping would like a chat.) The pattern is eye-glazingly familiar by now in the age of Donald Trump: Politician does or says something provocative (Orbán delights in assuring western nationalists that "liberal democracy" is "over"); an appalled political class overreacts; the anti-anti brigades man their battle stations; and around we go, dumbly, until the next controversy.

This depressing cycle may appear newish to American eyes, but it's old hat in post-communist Europe, where opportunistic pols learned early and often that you can gain and consolidate power by replacing the "commun" prefix with "national." Sometimes it would get bloody, as in Slobodan Milošević's Serbia; sometimes it could come off to outsiders as bloodlessly rational (as with the Czech Republic's Václav Klaus, who preceded Orbán in playing the Anglo-American right like a fiddle). But always, the nation is being besieged by globalists from without, undermined by possibly disloyal intellectuals from within, and requiring a father figure to navigate the treacherous waters.

When Trump escalatored successfully into our political lives, those of us foreign correspondents who covered three-time Slovak Prime Minister Vladimír Mečiar immediately began sending each other can-you-believe-it notes. A crudely entertaining, larger-than-life serial litigant barking conspiracy theories and crazy lies, while also steadfastly, democratically, venturing into corners of national life that the condescending elites had long abandoned? Generating unhinged hyperbole while also governing as an unhinged hyperbolist?

It was stunning to see such politics find fertile soil in a mature liberal democracy. And even after that hard-earned lesson in humility, it's jarring still to watch Americans kiss the ring of a prototype of the form, albeit one considerably more polished. (Mečiar once told me before a 1993 trip to the U.S. that he'd consider the visit a success if "people see that I don't eat children.")

Orbán can point to the electoral scoreboard—he's governed Hungary for the past decade, and most of this century—and he also whets the power appetites of American conservatives who no longer have patience for due process, individual autonomy, and limited government. "You are thinkers, but we are doers," the prime minister told a rapt audience at the February 2020 National Conservatism Conference in Rome. The I-wish-we-had-that-here fantasia at this point is right out front. "Orbán impresses," Dreher wrote this week at The American Conservative, "because he understands better than our own politicians the kind of wicked insanity we are up against."

But aside from electoral success, there are some aspects to Orbán's national-politics variant that are unique to Hungary and should be uniquely worrying to those of us who value freedom in the United States (which, Carlson's host-flattery notwithstanding, beats Hungary's like a drum).

Magyar grievance-nationalism begins with a wound the U.S. has never come close to absorbing—losing nearly two-thirds of its territory at the post–World War I Treaty of Trianon. Granted, Hungary's pre-war landmass was at an ahistoric high filled with subjugated minorities, but the peace agreement left millions of Hungarian-speakers stranded outside their native country.

Given the feebleness of interwar Hungary, the fascist irredentism of its Axis-allied WWII regime, then the Communist control after the war, this created not just an unrequited nationalism, but an unrequitable nationalism. Orbán's most fateful political choice (on which more below) came in recognition of a persistent national itch that can never fully be scratched.

The Hungarian language plays a key role in nurturing national paranoia, for the salient reason that almost no one else understands it. (Not even Finns, despite sharing the same linguistic family tree.) Poland and Czechoslovakia may have also been small countries frequently overrun by militaristic neighbors, but at least they shared the same Slavic roots as their Russian tormentors.

Hungarians, particularly in the capital, have long since mastered the art of presenting one face to the world in German, English, or Russian, quite another amongst themselves in their secret code of a mother tongue. Meanwhile, a majority of the country's 10 million people do not speak a second language, rendering them surrounded by sporadically hostile Slavs and German speakers they cannot comprehend.

Perhaps the biggest example of Tucker Carlson telling on himself during his great inter-nationalism adventure is when he said, "Every Hungarian I have met…had better English than our own president." Not only is the joke feeble; it's a confession that he never visited the part of the country that gave Viktor Orbán his political power in the first place.

This is where the unstoppable Hungarian encomia of the anti-globalist anti-elites finally meet an immovable paradox. Carlson, Dreher, and the Fidesz-fluffing brigades love-love-love them some Budapest. Love it! Not just the chest-puffing dual-monarchy architecture, but the sprawling street cafés, the flamboyant Franz Liszt sculptures, the foie gras, the bathhouses, the Tokaji, the Jewish quarter, the Turkish influence, the multilingual intellectuals, the stylish young things parading down endless pedestrian streets. It's all so sensual, so intoxicating, so…cosmopolitan. And Viktor Orbán has been politicking against the place for a quarter-century.

Almost every country has some version of the rural/urban divide; country mouse vs. city mouse. But almost nowhere is it so dominant as in Hungary, whose capital city, at 1.75 million, contains 18 percent of the country's population, and whose second city you've almost certainly never heard of. (It's Debrecen, at 200,000.)

Orbán started his political career as a pretty young thing, co-founding Fidesz (the Alliance of Young Democrats) with a bunch of Budapest university pals in 1988 as an anti-communist, pro-environment, pro-Western political movement that was originally—and spectacularly!—limited to those under the age of 30.

After getting around 5 percent of the vote in the 1990 parliamentary elections—the nationalist Hungarian Democratic Forum, with 24 percent, would run the government for the next four years—Fidesz put Orbán in charge of the party in 1993, upon which he made a fateful decision: No more would this be the party of young urban liberals; Fidesz would re-position to the center-right, stumping for the Puszta vote with consciously anti-cosmopolitan politics.

The Budapest liberals of the party, many of them Jewish, bolted in alarm (the country has a fraught history of murderous anti-Semitism), joining the Alliance of Free Democrats (SzDSz), a center-left anti-communist grouping that then shocked many Hungarians by joining the unreformed Socialist Party in an uneasy coalition government after the 1994 elections. (It should be noted here that Hungary's "goulash communism" was considerably softer than the totalitarianism of many Warsaw Pact countries, and that by some measures the mid-'90s Socialists were about as pro-market as Klaus' Civic Democratic Party in the Czech Republic.) In opposition, Fidesz and Orbán tacked increasingly nationalist and illiberal, and by 1998 that translated into Orbán becoming prime minister and SzDSz largely scattering to the wind.

Orbán has been the country's dominant politician ever since. And judging by one of the key measures Republicans used to care about, he has been a disaster.

In 1988, when Fidesz was just getting its start, Hungary and its goulash communism was far ahead of the regional pack in privatization, adopting market reforms, and the resulting GDP. As late as 1993, the country was still at or near the top of the Visegrád Group including Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia, and ahead of the newly independent Baltic countries of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

Ever since 2012, near the beginning of Orbán's current reign, Hungary ($15,900 in 2020 GDP per capita, per the World Bank) and Poland ($15,700) have been at the bottom of the pack, and not by a little—Estonia's up at $23,300, the Czechs are at $22,800, and even once-lowly Slovakia is kicking it at $19,200. Like a meal at McDonald's, nationalism looks tempting in the ads but doesn't digest particularly well.

Instead of examining his economic stewardship, or taking seriously critiques of his record, Orbán's American boosters are left cheering on his culture war triumphs from the luxurious comforts of Budapest's cosmopolitan excess. It's a bit like crediting Donald Trump for the civilizational glories of the Bay Area while cavorting in Nob Hill; it does not quite compute.

Worse, by aspiring to Orbán's strategic and proudly anti-liberal wielding of consolidated state power against perceived internal enemies, the Hungaro-cons are threatening to sink deeper into the conservative rut of anti-factual paranoia, enemy-scapegoating, and egg-breaking, swapping out even the pretense of philosophical governing principle for a transparent will to power.

"The key insight about Orban is that he believes that the future of his nation and of Western civilization hangs in the balance. He's right about that," Rod Dreher wrote last week, after a no-doubt sumptuous dinner in Budapest with Tucker Carlson. "I prefer the (possibly flawed) ways that Orban is meeting the crisis than the ways that the American Right is failing to do same."

So it's Flight 93s all the way down, then, only this time hijacked by a Hungarian. Perhaps one day the American right will regain its faith in America.

Show Comments (271)