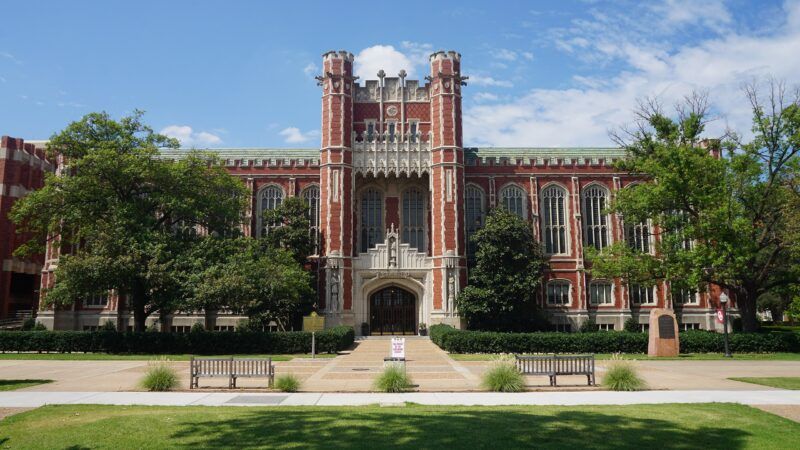

O.U. Anti-Racist Seminar: 'In the Classroom, Free Speech Does Not Apply'

A training session for graduate students urged them to prohibit students from discussing problematic views.

During an online training seminar for graduate students at the University of Oklahoma (O.U.), two presenters urged English instructors to purge all problematic speech from their classrooms. They even asserted—incorrectly—that the Supreme Court had empowered university employees to prohibit students from engaging in hate speech.

The Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) obtained a recording of the seminar, which was titled "Anti-Racist Rhetoric and Pedagogies." The hour-long video is worth watching in full, and contains a variety of unbelievable statements from presenters Kelli Pyron Alvarez and Kasey Woody.

During her remarks, Alvarez asserted that students in the English 1213 course—Principles of English Composition—sometimes come to class "emboldened to be racist, like overtly racist." The way to deal with this is to explicitly prevent them from making statements that might offend others. If any graduate students are worried about getting in trouble for silencing wrong-thinking students, never fear: Teachers have all the power they need to do so, according to Alvarez.

"If it continues to happen, report them for violating the student code of conduct," said Alvarez. "In the classroom, free speech does not apply."

She later clarified that she believes the Supreme Court "has actually upheld that hate speech, derogatory speech, any of the -isms, do not apply in the classroom because they do not foster a productive learning environment."

"As instructors, we can tell our students no, you don't have the right to say that, stop talking right now," she said.

This proclamation is stunningly wrong. The Supreme Court has never issued a ruling that prohibits "hate speech" on college campuses or anywhere else. Hate speech, in fact, is a subjective term: What someone finds hateful might nevertheless be objectively true, and more importantly, fully protected by the First Amendment. Indeed, the Supreme Court explicitly defended hateful expression in the 2017 case Matal v. Tam.

"Speech that demeans on the basis of race, ethnicity, gender, religion, age, disability, or any other similar ground is hateful; but the proudest boast of our free speech jurisprudence is that we protect the freedom to express 'the thought that we hate,'" wrote Justice Samuel Alito for the majority, quoting from a 1929 dissent by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

O.U. is a public university, and thus is bound to comply with the First Amendment. Instructors who deliberately squelch certain political opinions in a manner that is not viewpoint-neutral certainly risk running afoul of the Constitution.

"Professors cannot abuse their power to require students to personally adhere to a particular viewpoint or ideology," wrote FIRE's Daniel Burnett and Sabrina Conza. "As the AAUP has written, instructors have academic freedom of 'instruction, not indoctrination.' It can be hard to define precisely where this line falls, but there's no question that a significant amount of this workshop teaches participants how to indoctrinate instead of how to instruct."

Setting aside the legal issues, it's just plain wrong as a matter of educational policy to always and automatically forbid the discussion of any subject that might offend anyone for any reason. And a significant problem here is that the presenters never defined their terms, leaving listeners with the impression that they would suppress an extremely broad range of viewpoints.

Hilariously, Woody gave the example of asking students to share something about which they have a strong opinion.

"One of my black students said, 'Black Lives Matter,'" Woody recalled. "I said that is not an issue that I would take up. That's not an argument. It's a fact. Black lives matter. You are not obligated to listen to or entertain an argument that is trying to tell you your real experiences are not real because the person making that argument has never experienced them."

The presenter did not seem to grasp that her anti-racist pedagogy had actually prompted her to delegitimize the perspective of a student who was black.

"I usually look for my students who might be entertaining the idea of listening to a problematic argument," said Woody. "I say, 'We don't have to listen to that. That's not an argument we have to listen to.'"

This is a very bad approach to teaching. Specifically, it's a bad approach to teaching English composition, which is about how to write coherent essays and construct arguments. Instructors don't need to allow abject racial discrimination or harassment in the classroom, but proactively shutting down any potentially problematic discussion runs directly counter to the educational mission of the university.

Show Comments (76)