Biden's Long-Overdue Recognition of the Armenian Genocide Could—but Probably Won't—Produce a Foreign Policy Rethink

It's long since past time to separate accurate geopolitical language from military interventionism.

On Saturday, April 24, for the first time in 40 years, an American president summoned the courage to use the accurate term to describe a century-old war crime.

"Each year on this day, we remember the lives of all those who died in the Ottoman-era Armenian genocide and recommit ourselves to preventing such an atrocity from ever again occurring," President Joe Biden declared, in the White House's annual message marking the National Day of Remembrance of Man's Inhumanity to Man.

Previous residents of 1600 Pennsylvania Ave., most brazenly Biden's former boss Barack Obama, had shied away from using the word genocide to describe the organized Turkish slaughter of more than 1 million Armenians from 1915–1923, despite campaigning piously on the promise to call evil by its proper name. (Donald Trump never made that promise, though George W. Bush did.)

Why the cowardice? Because the subject is considered near taboo in Turkey, due to any whiff of suggestion that the sainted founder of the post-Ottoman country, Kemal Ataturk, might have his fingerprints near a crime scene. Over the years, Ankara has spent hundreds of millions of dollars on increasingly ineffective diplomatic efforts to prevent its fellow NATO members from using the g-word, implicitly threatening to revoke America's access to the strategically important Incirlik Air Base.

As former U.S. ambassador to Armenia John Marshall Evans—who was encouraged to resign from the State Department after publicly uttering the word "genocide" in conversation with the passionate Armenian-American diaspora—explained to me a decade ago, "Turkey is a hugely important ally, and little landlocked Armenia, population 3 million at best, is never going weigh in those scales in such a way as to even make a showing." From Washington's point of view, it was too much potential real-world pain for too little linguistic gain.

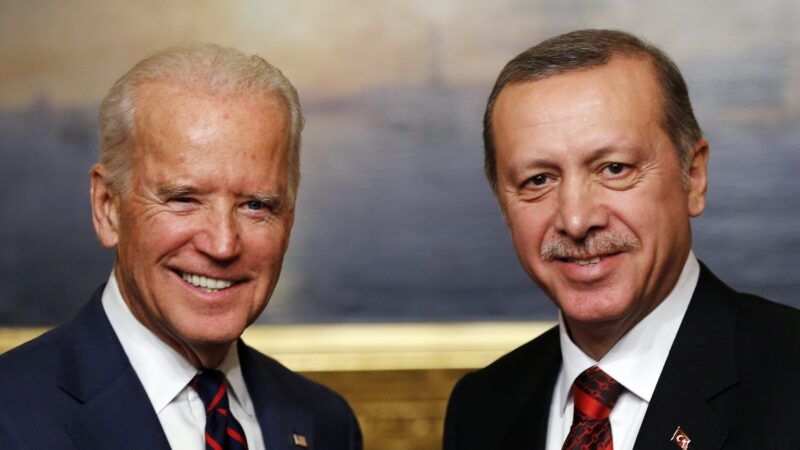

So what changed in 2021? Congressional impatience with the increasingly authoritarian Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, for one. The House and Senate in late 2019 each overwhelmingly passed, over Trump's objections, resolutions stating that "it is the policy of the United States to commemorate the Armenian Genocide through official recognition and remembrance."

Ankara and Washington have been at loggerheads over U.S. support for Syria Kurds (who Turkey regards as terrorist threats); Turkey's purchase of Russian missiles (which America believes could jeopardize NATO technology secrets), plus Erdoğan's human rights record, which Biden finds more appalling than his predecessor.

In a December 2019 interview with The New York Times, Biden called Erdoğan an "autocrat" and vowed to take "a very different approach to him now, making it clear that we support opposition leadership," helping them "to be able to take on and defeat Erdogan. Not by a coup but by the electoral process."

In a television address this weekend, Erdoğan called Biden's new wording "groundless and unfair," adding: "We believe that these comments were included in the declaration following pressure from radical Armenian groups and anti-Turkish circles." Erdoğan also advised his U.S. counterpart to "look in the mirror," since "we can also talk about what happened to Native Americans, Blacks and in Vietnam."

Many libertarians and other skeptics of U.S. military adventurism get tetchy when Washington escalates adjectives to describe faraway slaughter. For decades, "humanitarian interventionists" such as Madeleine Albright and Samantha Power and their neoconservative counterparts on the right have used the g-word, and in Power's case the Armenian genocide recognition explicitly, as a necessary precursor to the use of force. Obama, with Power's encouragement, used the spectre of a possible "massacre," "slaughter," and "mass graves" in Benghazi to justify his disastrous war of choice in Libya.

But the standard for language should be accuracy, not how words might be leveraged into disagreeable policy. One of the reasons that foreign policy "realism" has gotten such a bad name is that all too often it has been conflated (by practitioners as well as commentators) with realpolitik—with the situational ethics and conscience-straining two-facedness required by maneuvering through a fallen world.

In fact, it is interventionism that requires such grubby compromises, as I have argued when writing about Samantha Power and her ilk. We would care much less about the owners of Incirlik Air Base if we stopped using it so damned much. Using precise language undistorted by political necessities—which, to be fair, does not come naturally to the State Department—need not be a trigger to war. After all, Ronald Reagan, the last sitting U.S. president to use the phrase "Armenian genocide," was able to issue clear-eyed condemnations of several regimes he had zero intention of bombing.

The Biden administration could—but almost certainly won't—use America's long-overdue presidential recognition of the Armenian genocide to more firmly decouple language from interventionism, thus freeing up space for more blunt but less fraught international relations. As Thomas Jefferson said in the famous quote, whose overlooked emphasis is mine: "Peace, commerce and honest friendship with all nations; entangling alliances with none."

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Meh, it’s been awhile.

https://mobile.twitter.com/mattwelch/status/1102654202545913857?s=12

Making money online more than 15$ just by doing simple work from home. I have received $18376 last month. Its an easy and simple job to do and its earnings are much better than regular office job and even a little child can do this and earns money. Everybody must try this job by just use the info

on this page.....VISIT HERE

Matt Walsh, genocidaire.

Here is Job opportunity for everyone! Because of Corona Work from comfort of your home, on your computer And you can work with your own working hours. You can work this job As part time or As A full time job.MOi You can Earns up to $1000 per Day by way of work is simple on the web. It's easy, just follow instructions on home page,

read it carefully from start to finish Check The Details...… Home Profit System

Yes, it’s long overdue, but will amount to little more than virtue signaling. Fact is the US (and Israel) still need Erdogan more than he needs them.

Well yeah, ignoring China's ongoing genocide after it was officially declared by the USG, means the Biden administration can use the word freely and without consequences now. The precedent is set. It no longer matters, so the cost to acknowledge it is minimal.

Especially since the Armenian Genocide happened over 100 years ago during a time of war while the Uyghur Genocide is happening right now just for the hell of it.

What difference, at this point, does it make?

Interesting the role the Kurds played then and now. Historian Margaret MacMillan, in Paris 1919, https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/26348.Paris_1919

that the Kurds were largely used as the enforcers of the Armenian genocide for multiple reasons: they were a separate ethnic group from the other Turks and that allowed some plausible deniability from Ankarta, they had an especially strong hatred for the Armenians (though they pretty much hated everyone and vice-versa), and they simply gave no shits. It really was a forerunner for Hitler. Germany likely would have known much about the genocide since Germany and the Ottomans were allies operating jointly in Asia Minor and points nearby. Wilson detested the Kurds largely because of the knowledge of their particular role in the genocide and prevented (or greatly participated in preventing) them from getting their own country in the break-up of the Ottoman Empire. The Brits, for their part, wanted a buffer between their new toy -- Iraq, and its oil fields -- and the Turks and then the Bolsheviks to the North. Anyone coming from that way would have to get through the semi-autonomous and dangerous Kurds, who while formidable would be weakened by not having a country and being spread among Turkey, the newly bordered Iraq and Iran. And here we are 100 years later.

It really was a forerunner for Hitler.

Nonsense. I have it on good authority that Hitler never harbored any racial animus until he read about the US' Jim Crow laws.

I have it on better authority that Hitler's racism only came to the fore after WWI. His fellow soldiers never noticed his anti-semitism. And Hitler would have seen Jewish soldiers fighting bravely along side him. He also owed his career as an artist, modest as it was, to Jewish dealers in pre-war Vienna.

Thanks. That’s one of the most astute comments I’ve encountered on the ME. BP at work?

Is there any place the Brits haven’t screwed up? We are following their example recently.

Biden- calls it a genocide (rightly) and stands up to Turkey.

Trump- let's Erdogan's goons beat up American citizens and does nothing.

Profiles in courage indeed.

What makes you think that anything will change? Presidents have routinely complained about China’s human rights abuses while sucking their dick under the table. They will continue to do so with Turkey. I am happy that Biden called it what it is/was, but doubt anything will change. After all, the US Armenian community is tiny (mostly in LA and Boston areas), with little political clout, while Turkey is a huge purchaser of US weapons and buddy of Israel.

Turkey is a huge purchaser of US weapons and buddy of Israel

Don't forget that the US has military bases, including nukes, in Turkey. Maintaining our footprint over there without Turkey would be very difficult.

That is a dimension Welch seems to ignore; namely, how the Turks will act in response. I don't think anyone really knows. But I don't imagine we will like it very much. Turkey has been an ally of convenience for 70 years or so. Do they really need protection from Russia?

The ball buster is that we have a legally binding treaty with them (NATO).

Meh - I gather Biden's conversation with Erdogan the other day was a form of negotiation-in-advance. Erdogan may not need need us, but I doubt he'd be flexing his muscles in Syria and Libya with such confidence as he has if he didn't think US presence in Turkey causes some hesitation in Russia.

The ball buster is that we have a legally binding treaty with them (NATO).

Indeed. He keeps nearly getting himself kicked out, but since the whole purpose of the organization is containing Russia, well . . .

I'm surprised that whatever special weapons were stored at Incirlik, weren't quietly yeeted after the last time Erdogan had a tMUDHEN. Nifty concrete vaults or not.

It's silly anyway: any special weapons nowadays are going to ride into theater from Whiteman, Diego, or Barksdale. Not off an F-16 or Mudhen.

Well, that was weird. "Erdogan had a tantrum," like during his, "Dude, that totally was a coup!" period.

Yeah - he's long seemed an . . . unreliable partner. I, too, wonder whether it's still necessary in this day and age to stage so much stuff over there anymore, but I'm far from a military expert.

"sucking their dick under the table"

Clinton's campaign to allow China to join the WTO was above the table. You'd know that if you had been paying attention at the time.

"while Turkey is a huge purchaser of US weapons"

I don't think it made Reason, but in 2019 Turkey purchased the Russian made S-400 air defense system, which the US complains is incompatible with the F-35 fighters, and began sanctioning Turkey under the Trump administration. Biden is continuing the pressure.

"and buddy of Israel"

Quit reading the news once Erdogan got into power, huh.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Israel%E2%80%93Turkey_relations#Deterioration_of_relations

Actually, Erdogan has spoken a lot against Israel lately and with Israel's newly-discovered reserves of Tel Aviv Tea bigger than Saudi Arabia's, Israel doesn't need oil from Turkey or anyone else.

This.

Israel gets nothing but headaches from Turkey for the past two decades.

"Biden- calls it a genocide (rightly) and virtue-signals to Turkey'

Fixed it for ya, lefty shit.

It was a genocide of Armenians, but that was a century ago, and no perpetrator is alive.

Meanwhile you and your bae Chou Bai-den, are actively sucking the cock of an autocrat perpetrating a genocide right fucking now.

So I suppose 2121 is when we finally declare the Chinese genocide of ethics groups huh. Assuming the US is still one country by then I guess.

"So I suppose 2121 is when we finally declare the Chinese genocide of ethics groups huh"

CNN, BBC, NYT etc have been declaring it for decades. Turkey has only recently joined the bandwagon.

So perhaps Kim Kardashian WILL be getting a reparations check from Ankara?

At long last her suffering will be alleviated.

She probably has got the equivalent just from clicks on the sly from horny Turks.

an American president summoned the courage to use the accurate term to describe a century-old war crime

Bullshit! There's no scientific evidence, blah blah blah, I read this book that says, greedy Armenians lying to make money. yadda yadda yadda...

This is not a small issue. The Armenian Genocide was the real thing - and it is not taught in schools. Unless you understand the Armenian Genocide, you won't put the Holocaust in context - or the California Genocide, for that matter. It's very important.

"California Genocide."

You might be facetious here, but you've got a point. The eradication of the California Indian, is probably the closest this country's come to abject genocide

Though we certainly gave it the old college try during the Phillipine Emergency.

Armenia and Azerbaijan have had a “mild war” the past few years. The Caucasus is almost as balkanized as the Balkans.

Every valley pretty much hates every other valley. See Beslan for how bad it can get.

“Biden called Erdoğan an "autocrat" and vowed to take "a very different approach to him now, making it clear that we support opposition leadership," helping them "to be able to take on and defeat Erdogan. Not by a coup but by the electoral process."”

Which, of course, is in no way comparable to the Russians taking sides in our electoral process.

And probably every bit as effective.

Or the U.S. State Dept running propaganda campaigns opposing the Putin-friendly candidates in the Ukranian elections under SecState Hillary Clinton...

It's no accident that the MSM needed to ignore the actual motivation that led to the stuff Putin got into tended to be a little more anti-HRC (when it was actually related to the election rather than just about sowing division and discord, including organizing a number of the early "#Resistance" rallies in the days following the 2016 vote).

Was Corn Pop one of The Ottomans?

So if Biden doesn't recognize it, did it actually happen?

If a geriatric tree falls while boarding Air Force One, does it make a sound?

Hey now! No Baby Groot jokes here.

I know you're snarking re: Biden, but it did and given the real-politic from then until now, the west has been reluctant to call Turkey on the matter.

But then (can't find it above) the valley-to-valley issues there meant is was but a bit larger massacre than the others.

Recognition is not the issue. I'm sure Trump, Obama and the rest of them 'recognized' the massacre. What Biden has done is publicly stated the issue.

While we are letting it all out, we should probably mention that the Turks have been killing Kurds on their southern border with glee. When the Kurds fled from Saddam in 93-94, the U.S. stepped up and started operation Provide Comfort and protected the Kurdish refugees from Saddam's forces. A NATO "no-fly" corridor was established to keep any Iraqi aircraft at bay, and US soldiers went in to organize food drops to feed the Kurdish refugees.

When US helicopters were visiting refugee sites from Turkey, the Turks required each helicopter to have a Turkish "Liason" Officer on every bird. The Turkish "liason" was just a spotter, he was marking targets. Months later, the Turks at Incirlik would declare a "no fly day" for NATO aircraft. Then, Turkish fighter bombers would be lifting off all morning on burner to get off the ground with a max load of bombs for those refugee camps that US forces had just fed. Does anyone remember Billy Clinton mentioning any of this?

Yup Erdogan destroyed the relationship with the US and this is a result of that. He also destroyed what was once a friendly relationship with Israel.

Turkey has few friends anymore. Their once booming economy is no longer. Buying the Russian missile system got them kicked out of the F-35 program. Their was one coup attempt and he has gutted the military and civilian leadership. He has destroyed the constitutional democracy and appointed himself dictator.

But, hey, have you ever...been in a Turkish prison?

The word "genocide" didn't exist in 1915. It was created to describe both the mass killings of Armenians in WW1 and the Holocaust in WW2.

The fact that it's ever been controversial to apply the word to one of the events which literally lead to its invention demonstrates how craven and non-sensical so much of politics (especially international politics) has probably always been.

As far as I know, the Armenian genocide is only controversial in Turkey. Internationally, it is well understood and uncontroversial. It is controversial in a national context, underlining the limitations and dangers of nationalism.

It's forbidden in the circles of diplomats and international power-brokers attempting to pimp themselves to get favor with Turkey and it's Islamists.

Academics also poo-poo the Armenian Genocie if they want or get educational grants from Turkey to their institutions. Even anti-Islamist scholar Bernard Lewis doesn't use the word "genocide" with regard to Turkey's actions, which shows the depths of the corruption going on with this subject.

"which shows the depths of the corruption going on with this subject."

One dead academic is not what I call deep. Denial of the Armenian genocide is deeply ingrained in one nation - Turkey. Outside it is almost universally accepted.

Notice I said "Even anti-Islamist scholar Bernard Lewis." There is far more than one academic that is involved.

Moreover, Armenian Genocide denial is part of the even larger academic millieu of pro-Islamist, pro-Third World, anti-West, Under-Dogmatism. This environment equally praises Coercive Utopianisn throughout the world and equally denies and erases it's victims.

"There is far more than one academic that is involved. "

Of course, I agree. In Turkey. Outside they are few and far between. And Trump and Obama etc don't deny the genocide. They simply remained silent on the issue out of expediency.

"Armenian Genocide denial is part of the even larger academic millieu of pro-Islamist, pro-Third World, anti-West, Under-Dogmatism. "

I suspect you know little to nothing about what happens in these institutions, and what you do know comes third hand from unreliable sources.

Indeed. In fact, Hitler was inspired by the Armenian Genocide because it convinced him it was possible to exterminate whole groups of people. On the eve of Nazi Germany's invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, Hitler rhetorically asked: "Who remembers the annihilation of the Armenians?"

If we can see a fly's ass from 100 miles in space and can drone or ICBM anyone from anywhere, and if we have enough crude, shale, and Uranium under our crust to last indefinitely, then we do not need Turkey or Erdogan or NATO for anything! Say the word "genocide," call it exactly what it is, and get it over with!

Since I started with my 0nline business, I earn $25 every 15 minutes. It s0unds unbelievable but you vvon’t forgive yourself if you d0n’t check it out.

Learn more ab0ut it here..

………………… http://www.Cash44.club

Wait we are going to interfere in another countries elections? Does anyone see the hypocrisy here? We ever lose the reserve currency and this crap stops pretty quick.

That said good for Biden to say this..we still have issues around calling the holodomor what it was...due to an anti-semitism fear. I recall an Israeli academic who said of course it was a planned genocide but because so many of the bolshevik's in charge of the policy were Jewish it can't be admitted as such as it would fuel historical anti-semitism. But in the end the truth is the truth..and all holocausts should be exposed for the horror they are.

It wasn’t a genocide.

It was a war in which the losers were targeted. Both sides were combatants.

Calling it a genocide is inaccurate and improperly casts aspersions on a current people and government that didn’t even exist 100 years ago

How the heck were unarmed Armenian civilians combatants? You've either bought into a pack of lies, or are a paid propagandist spreading lies.

But we’re supposed to pretend he’s a warmonger because of a vague allegation of drone strike (presumably against the man that ordered a terrorist attack on Americans) https://wapexclusive.com ,

You’re an ignoramus and willfully idiotic, and it’s hard to tell whether you believe what you do because you’re uninformed or whether you’re uninformed because you’re stupid.