Despite Its Much Stricter COVID-19 Policies, California's Per Capita Death Rate Is Only Slightly Lower Than Florida's

The comparison poses a puzzle for people who believe lockdowns were crucial in controlling the pandemic.

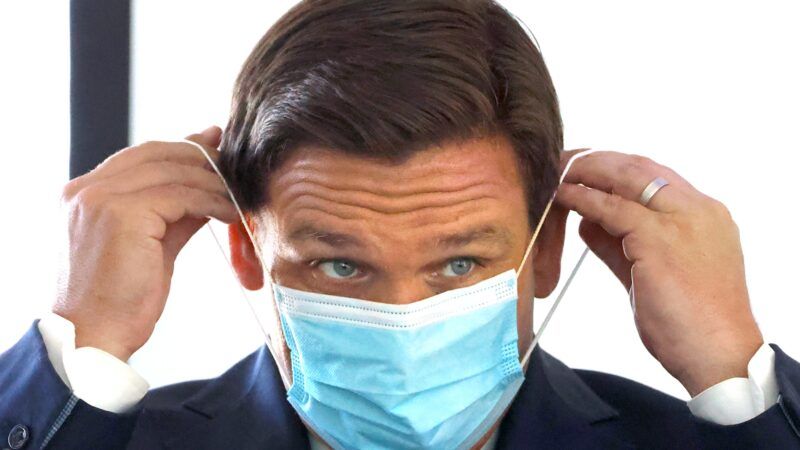

California led the country in imposing COVID-19 lockdowns last spring, and Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) kept broad restrictions in place longer than many other governors, lifted them more gradually, and repeatedly re-imposed them. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R), by contrast, was widely criticized for belatedly ordering a less sweeping lockdown, lifting it too early, and allowing social, educational, and economic activity to continue with modest restrictions even as cases surged in the summer and winter. Yet California's per capita COVID-19 death rate, according to Worldometer's numbers, is just 7 percent lower than Florida's, despite Florida's substantially older population, which should have made the state more vulnerable to the disease.

That comparison presents a puzzle for people who believe broad government-imposed restrictions have played a crucial role in controlling the pandemic. A Los Angeles Times story published yesterday tries to solve the puzzle without abandoning the conviction that Newsom's strict policies were both necessary and cost-effective. The result is a hodgepodge of straw-grasping arguments that reveal how impervious that conviction is to evidence.

Florida currently ranks 27th on Worldometer's list of states with the highest numbers of COVID-19 deaths per capita, just a few notches above California. The top four states—New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts—all imposed strict controls similar to California's, as did half of the top 10 states.

In 2019, according to the Census Bureau's American Community Survey, 21 percent of Floridians were 65 or older, compared to 15 percent of Californians. The median age is 42.2 in Florida, compared to 36.8 in California. Based on those differences, it was reasonable to expect a higher death toll than Florida actually has seen, since COVID-19 risk rises sharply with age.

According to estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the infection fatality rate for Americans who are 70 or older is something like 5.4 percent, compared to 0.5 percent for 50-to-69-year-olds, 0.02 percent for 20-to-49-year-olds, and 0.003 percent for people younger than 20. In other words, the risk for the oldest age group is 11 times the risk for the next oldest, 270 times the risk for 20-to-49-year-olds, and 1,800 times the risk for the youngest cohort.

Yet Los Angeles Times reporters Soumya Karlamanga and Rong-Gong Lin II, citing University of Florida epidemiologist Cindy Prins, write that "Florida's older population might have, perhaps counterintuitively, prevented the virus from spreading as quickly as it did in California." How so? "Young adults who socialize and mingle, either at work or in social settings, tend to spread the virus the most while older people are more cautious and stay home."

Florida, of course, is a mecca for college students on spring break, whose socializing and mingling provided ammunition for critics of DeSantis' alleged recklessness. And despite the relative timidity of elderly Americans, they account for more than four-fifths of COVID-19 deaths in the United States. Nursing homes alone account for more than a quarter of the total death toll.

Karlamanga and Lin also try to blame the weather. "The dry air in California," they suggest, gave the state a disadvantage "compared to humid Florida." While "researchers are still learning about how climate affects the coronavirus," they say, "some studies suggest that when the air is humid, virus droplets fall to the ground faster, so people are less likely to become infected."

A 2020 review of 17 studies on this subject did indeed conclude that "warm and wet climates seem to reduce the spread of COVID-19." But the authors said "the certainty of evidence was graded as low" and added that "these variables alone could not explain most of the variability in disease transmission." It is also worth noting that humidity did not seem to have much of a protective effect in Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama, Arkansas, South Carolina, or Georgia, all of which have per capita COVID-19 death rates above the national average.

Karlamanga and Lin also cite "higher levels of poverty, density, [and] overcrowding" in California, which certainly could have contributed to the state's death toll. Still, if California's COVID-19 policies were as vastly superior to Florida's as the Times seems to think, you would expect to see a much bigger difference in outcomes.

The effectiveness of Newsom's crackdowns in the fall and winter is especially hard to discern. Despite its much stricter policies, California saw a bigger winter surge in newly identified infections than Florida did, and daily new cases peaked in both states (and nationwide) around the same time.

Karlamanga and Lin say "some public health experts…acknowledge that California's strict rules became less effective as exhaustion set in by late 2020." But on the face of it, there was no public health payoff at all from the lockdown Newsom imposed in early December. Even San Mateo County Health Officer Scott Morrow, a leading advocate of lockdowns last spring, was dismayed by that order, which he viewed as illogical, inconsistent, and scientifically unsupportable. "I'm not sure we know what we're doing," he confessed.

The Times does implicitly find fault with at least one aspect of California's policies. Karlamanga and Lin say Florida's "warm weather allowed people to congregate outdoors year-round, a low-risk activity." While California also has warm weather, outdoor gatherings were "banned in many parts of California for months." Citing Prins, Karlamanga and Lin say that decision "may have backfired," encouraging people to gather indoors, away from the government's prying eyes. Yet the Times also blames "weak enforcement" of California's rules, which in this case seems like a blessing.

Wall Street Journal editorial writer Allysia Finley describes Florida's relatively good ranking as "a vindication for Ron DeSantis," who did a much better job of protecting especially vulnerable residents from COVID-19 than states like New York and New Jersey while avoiding the social, economic, and psychological costs associated with prolonged and repeated lockdowns. "Employment declined by 4.6% in Florida in 2020, compared with 8% in California and 10.4% in New York," Finley notes. "Leisure and hospitality jobs fell 15% in Florida, vs. 30% in California and 39% in New York."

As these dueling interpretations show, there is only so much that can be learned by comparing two jurisdictions with starkly different COVID-19 policies. More systematic studies likewise have reached contradictory conclusions. Some researchers have concluded that lockdowns had an important impact, while others say there is little or no evidence that they affected mortality rates or trends in cases. According to a Nature Human Behaviour study of 226 countries published in November, "a suitable combination of NPIs [nonpharmaceutical interventions] is necessary to curb the spread of the virus," but "less disruptive and costly NPIs can be as effective as more intrusive, drastic ones (for example, a national lockdown)."

In a 2020 National Bureau of Economic Research paper, UCLA economist Andrew Atkeson and two other researchers looked at COVID-19 trends in 23 countries and 25 U.S. states that had seen more than 1,000 deaths from the disease by late July. After finding little evidence that variations in public policy explained the course of the epidemic in different places, they concluded that the role of legal restrictions "is likely overstated." That much seems safe to say in light of more recent experience in the United States.

Show Comments (105)