On This Presidents Day, Stop Worshiping the Imperial Presidency

Presidents aren't saints. They aren't monarchs. They aren't celebrities. And they aren't your friends.

Ah, Presidents Day: a much-needed moment to slow down and commemorate presidents past and present, because we definitely don't have enough of that in this country.

I jest!

Walking around Los Angeles, you'd be hard-pressed not to pass someone sporting BIDEN-HARRIS merchandise—a shirt, a bumper sticker, a sweatshirt, a mask. Back where I grew up in Virginia, the same is true, though they have a different hero: For years, "MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN" adorned the lawns, cars, and hats of those who wanted you to know they stood, and perhaps still stand, with former President Donald Trump.

That's not news. Public displays of affection for the U.S. president have become standard in everyday American life, extending well past election cycles and rock-concert-esque inaugurations, as if who you voted for is a personality trait. That's the conventional wisdom, it seems. So, on this fair Presidents Day, a reminder: Presidents aren't saints. They aren't monarchs. They aren't celebrities. And they aren't your friends! The executive leader is an employee of the country—someone whose job was, and still should be, limited in size and scope.

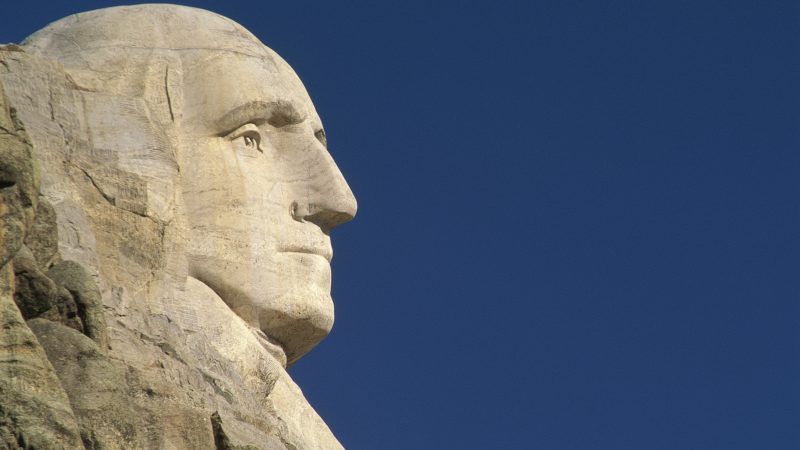

It has become something decidedly different over the years, with each president becoming more powerful than the last. That maybe explains, to some degree, why the political fangirling has grown in tandem. Though I can't step back in time to the 18th and 19th centuries, I would venture to say Americans weren't donning shirts with presidents' faces or branding horse-drawn carriages with the names of current and erstwhile U.S. leaders. Nor do I think former President George Washington, whose birthday serves as the inspiration for this holiday, would have wanted that sort of hero worship, when considering that the bedrock of America's founding specifically sought to create a new order—one without a king or king-like figure.

"The founders of our republic did not want to put that much [power] in the hands of a single leader," Mark Rozell, the founding dean of the Schar School of Policy and Government at George Mason University, told The Christian Science Monitor. "America's addiction to executive power has become dangerous for this country."

Similar to the idolatrous presidential merchandise, the bloating of the executive is not a problem exclusive to Republicans or Democrats. "Early in the 20th century, it was the left, the progressives, that wanted a dominant and domineering presidency," Gene Healy, a vice president at the Cato Institute, observed in a recent Reason TV documentary. "Later in the 20th century, it's the conservatives that see their political salvation in a strong executive branch."

Healy notes that "crisis tends to give you power on steroids." And, if history is any sort of indication, that's certainly true. "World War I, the Great Depression, World War II, the Cold War, 9/11, and the financial collapse of 2008: All of these led to a concentration of power in the executive branch," he says. "There's a ratchet effect when it comes to presidential power. Each new executive power grab that a new president makes is rarely given back."

Congress often declines to fight such expansions when the majority shares a party affiliation with the president. But little thought is given to what will happen when future leaders—ones without their ideological priors—have those same powers.

It's an attitude that appears to be lost on the bulk of partisans today. Take the most recent crisis: COVID-19. Early on in the pandemic, Trump proclaimed that he would reopen the U.S. economy by fiat in April, which, predictably, was met with a big "no" from many scientists, activists, and leaders. The proposal was farcical on its face; thanks to federalism, he had no authority to impose that will on the states. It seemed obvious. Yet many of those same scientists, activists, and leaders wanted him to implement a national lockdown, as if the constitutional question was somehow different. What?

With President Joe Biden now in the Oval Office, some have been more honest in their support of that approach. "The Democratic margin in the Senate—zero—is too slim for Mr. Biden to push ambitious laws through Congress, which is balky and slow even when majorities in both houses are broadly in agreement with the president," writes Eric Posner, a law professor at the University of Chicago, in The New York Times. "A weakened presidency," he continues, "would hamper national governance, and Democratic policies in particular."

Democrats, according to Posner, benefit more from a heightened executive role than do Republicans, particularly on issues like climate and immigration. But that comes with a huge caveat: "True, when Mr. Trump took power, he reversed some of Mr. Obama's unilateral actions, causing damage to the environment, the immigration system, health insurance and financial regulation," says Posner. "He also used his unilateral powers to unleash a destructive trade war."

Put more plainly, those in Posner's camp are "in for a rude surprise when the other team wins," concludes Reason's Jacob Sullum. For now, however, the tug of war continues: Biden kicked off his tenure with a series of executive orders, many of which just undid Trump's free-flow of directives.

That cognitive dissonance isn't going away anytime soon, and it will take quite some time before we see the air let out of the presidency. Maybe we never will. But we can apply that same mindset to how we approach the office. So celebrate this Presidents Day for what it is: a three-day weekend with time to recharge, free of president-forward fashion choices and political prayer candles.

Show Comments (500)