Reviving Sedition Prosecutions Would Be a Tragic Mistake

The ugly history of sedition trials

"That's insurrection against the United States of America," MSNBC's Joe Scarborough declared after an angry mob overran the U.S. Capitol. "If Donald Trump Jr., Rudy Giuliani, and Donald Trump are not arrested today for insurrection and taken to jail and booked—and if the Capitol Hill police do not go through every video and look at the face of every person that invaded our Capitol and if they are not arrested and brought to justice today—then we are no longer a nation of laws and we only tell people they can do this again."

Scarborough isn't the only one thinking along those lines. The airwaves have been filled with calls for charging not just the people directly involved in the riot but the people who spoke at the rally beforehand. The word sedition is getting thrown around a lot. Merriam-Webster reports that searches for the word spiked an amazing 1,500 percent on January 6, the day of the violence.

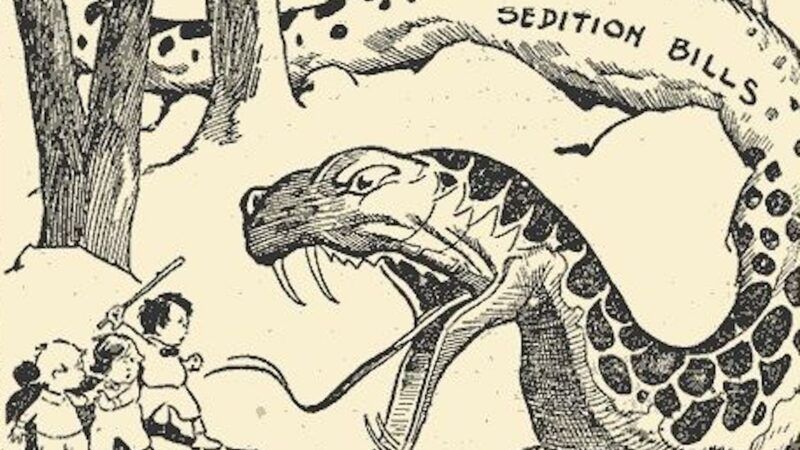

That would be a tragic mistake. The history of sedition prosecutions is rife with injustices, and the precedent, once established, becomes a grotesque Frankenstein monster. In many cases, the same people demanding prosecutions end up, when political fashions change, facing prosecution for the same offense.

World War II provides two classic examples. President Franklin Roosevelt's administration initiated two mass sedition trials under the 1940 Smith Act, formally known as the Alien Registration Act, which made it illegal to "advocate, abet, advise or teach" the violent overthrow of the U.S. government.

The first prosecution was against 23 members of the Socialist Workers Party, a Trotskyist group, for conspiring to overthrow the government by force. As is typical of these cases, the government never provided any evidence that the defendants had specific plans to do this, focusing instead on the potential that their abstract Marxist boilerplate condemning "capitalist wars" or playing up wartime injustices, such as police brutality, might incite insurrection.

Later in the war, the federal government hauled up 32 anti-Semites and other right-wing extremists in the largest mass trial in Washington, D.C., history. Most of them didn't even know each other before the indictment. The evidence was just as tenuous as the evidence against thr Socialist Workers Party. According to prosecutors, the defendants' writings against Roosevelt's foreign policy may have had an injurious influence on some members of the armed forces, undermining U.S. security. This, it was argued, was reason enough to send them to prison.

In these trials, the administration had support from members of the Communist Party. Only two years after the war ended, the government began prosecuting Communists under the same statute.

Those who want a new round of sedition prosecutions make the same argument: that inflammatory language—no more heated than in countless other rallies and demonstrations held every year—should be punishable because others may be moved to act.

None of the people now being singled out for political or legal retribution explicitly advocated the violent overthrow of the U.S. government, or even the violent occupation of the U.S. Capitol. Prosecutors, therefore, should concentrate on those who actually breached the building.

At times like this, we would all do well to remember the words of the late Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas in the 1949 case Terminiello v. Chicago.

Father Arthur Terminiello, a right-wing priest, had been convicted of inciting a riot after a fire-breathing speech in which he criticized Communists, Jews and others and condemned the protesting crowd outside the auditorium where he was speaking. In an opinion written by Douglas, an uncompromising defender of the First Amendment, the Court struck down the conviction. While Douglas deplored the content of Terminiello's speech, he argued that "a function of free speech under our system of government is to invite dispute." Speech, he wrote, "may indeed best serve its high purpose when it induces a condition of unrest, creates dissatisfaction with conditions as they are, or even stirs people to anger."

Trump's inflammatory rhetoric may well be worthy of impeachment and removal. In my opinion it is. But, in and of itself, it was not a crime worthy of jail time. Not unless we want to go down the ugly road of criminalizing strong or misguided opinions on a mass scale.

Show Comments (105)