Increases in Opioid-Related Deaths Show That Drug Warriors (Including Biden) Have No Idea What They're Doing

After a slight drop in 2018, fatalities involving opioids jumped last year, setting a new record that is apt to be broken this year.

Last year President Donald Trump bragged that "we are making progress" in reducing opioid-related deaths, noting that they fell in 2018 "for the first time since 1990." That 1.7 percent drop was thin evidence of success at the time, and it looks even less impressive in light of the the 6.5 percent increase recorded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2019. When you add preliminary CDC data indicating that opioid-related deaths rose dramatically this year, you have even more reason to wonder whether the government is actually winning the war on drugs.

The 49,860 deaths involving opioids that the CDC counted in 2019 set a new record that is likely to be broken when the data for 2020 are finalized. "Synthetic opioids other than methadone," the category that includes fentanyl and its analogs, were involved in 73 percent of opioid-related deaths last year. According to the CDC's preliminary data, "the 12-month count of synthetic opioid deaths increased 38.4% from the 12 months ending in June 2019 compared with the 12 months ending in May 2020."

During the same period, total drug-related deaths rose by 18 percent. Although that includes increases in deaths involving cocaine and methamphetamine, the CDC says, "synthetic opioids are the primary driver," and "the increases in drug overdose deaths appear to have accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic." As Zachary Siegel notes in a New York magazine piece, the pandemic and the lockdowns it inspired probably have driven drug-related deaths in two main ways: by contributing to the economic woes and social isolation that make drug use more appealing and by increasing the likelihood that people will use drugs without anyone else around, which magnifies the risk of fatal outcomes.

Although the pandemic and the restrictions associated with it have made matters worse, opioid-related deaths were already on the rise, which suggests once again that reducing access to prescription pain pills, the main thrust of the Trump administration's strategy, has not had the intended effect. To the contrary, it has driven nonmedical users toward black-market substitutes that are more dangerous because their potency is inconsistent and unpredictable, while depriving bona fide patients of the medication they need to make their lives bearable.

Although the government has succeeded in driving down opioid prescriptions, the upward trend in opioid-related deaths has not just continued but accelerated. In 2019, "natural and semisynthetic opioids," the category that includes commonly prescribed pain relievers such as hydrocodone and oxycodone, were involved in 24 percent of opioid-related deaths (many of which also involved fentanyl and/or heroin). That's down from 52 percent in 2010. Meanwhile, opioid-related deaths rose by 136 percent, while the fraction involving synthetic opioids increased from one-seventh to nearly three-quarters. That does not seem like a good tradeoff.

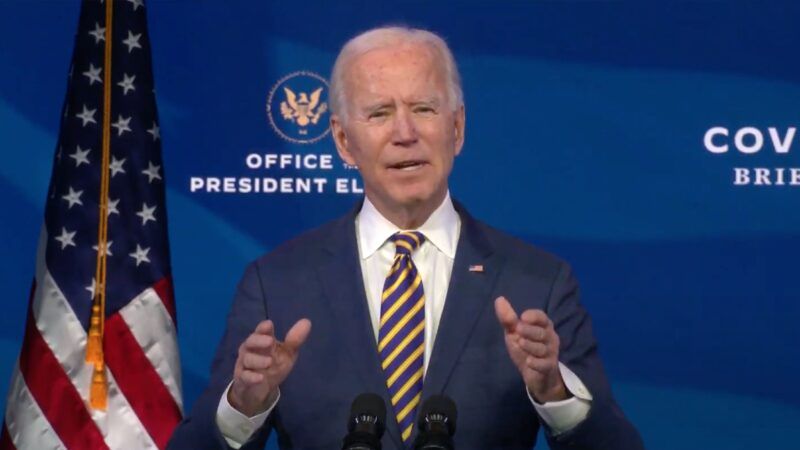

President-elect Joe Biden's "Plan to End the Opioid Crisis" promises more of the same. Biden emphasizes access to "substance use disorder treatment and mental health services"—a big Trump talking point. Biden wants to "hold accountable big pharmaceutical companies, executives, and others responsible for their role in triggering the opioid crisis," which the current administration also has tried. Such lawsuits and prosecutions might make drug warriors feel good, but they do absolutely nothing to reduce opioid-related deaths.

Biden promises to "stem the flow of illicit drugs, like fentanyl and heroin, into the United States." Why didn't anyone think of that before? To the extent that such supply control efforts succeed, they drive traffickers toward more potent and concealable products. That helps explain why heroin has been displaced by fentanyl, which is far more potent, and fentanyl analogs, some of which are more potent still. The proliferation of such drugs increases the variability that makes black-market opioids more lethal than legally produced narcotics.

Worse, Biden says he will "stop overprescribing while improving access to effective and needed pain management." We know from years of experience how the government is apt to strike that balance, and it is bad news for patients and nonmedical users alike.

Biden wants to expand "drug courts" as an alternative to "incarceration for drug use," but his plan hinges on the threat of incarceration for people who do not want the "treatment" he thinks they should have. And even those who comply will still be treated like criminals. "I don't believe anybody should be going to jail for drug use," Biden said during an ABC "townhall" in October. "They should be going into mandatory rehabilitation. We should be building rehab centers to have these people housed." Biden, who in the late 1980s was saying "we have to hold every drug user accountable," now wants to lock drug users in "rehab centers" rather than prisons.

Biden's plan says nothing about harm reduction measures such as fentanyl test kits, supervised consumption facilities, or expanding "medication-assisted treatment" beyond methadone and buprenorphine (although it does recommend looser restrictions on buprenorphine). The plan mentions "harm reduction" just once, and the phrase is immediately followed by a list of law enforcement initiatives. It looks like Biden, despite all his compassionate talk, will replicate the strategy that is helping to sustain the "opioid crisis" he says he wants to end.

Show Comments (65)