The Rust Belt Made Trump President. The Bet Hasn't Paid Off.

If Trump loses his bid for re-election, it will be because Rust Belt voters abandoned him after four years of misguided economic policies.

Four years ago, Donald Trump's final pitch to voters came during a near-midnight rally in Grand Rapids, Michigan, on the eve of the election.

"If we win Michigan, we will win this historic election, and then we truly will be able to do all of the things we want to do," Trump said. "They won't be taking our jobs any longer."

He did win Michigan—and Ohio, and Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. A Rust Belt sweep carried Trump to his unlikely victory in 2016. Those same four states will probably play an outsized role tomorrow in determining whether Trump gets another four years in the White House. There will be many ways to read the outcome of this week's presidential election, but on some level it is undoubtedly a referendum on the promises Trump made to voters in the industrial (and post-industrial) parts of the country.

Within days of the 2016 election, Trump and his top economic advisor, Peter Navarro, were talking about helping those Rust Belt voters by slapping tariffs on goods from Canada and Mexico. It took until March 2018 for Trump's long-sought trade war to get going, and until July of that year for it to become focused on China. Now, more than two years later, the tariffs Trump imposed on steel, aluminum, washing machines, solar panels, and loads of goods made in China have cost American consumers and businesses more than $57 billion annually.

Trump has always claimed that China is paying the cost of the tariffs, and that has always been a lie. More articulate proponents of the president's trade policy claim that the cost of the tariffs is worth their benefits: There's no gain without some pain, they argue.

But as the president faces re-election, the gains are hard to find. And that's especially true in the Rust Belt. Manufacturing job growth in those four key 2016 swing states slowed almost to a standstill even before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, as Trump's tariffs hiked costs for imported goods and materials used by American manufacturers. Those higher import taxes, in turn, blunted business owners' ability to make the investments that create new jobs.

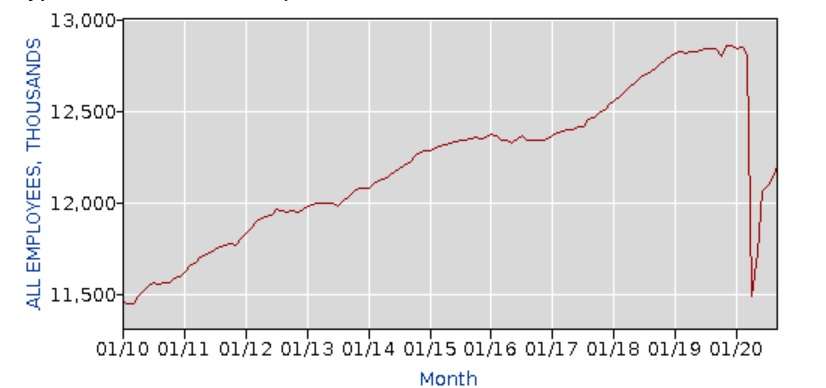

The economic data tell the most obvious part of the story. When Trump was inaugurated in January 2017, those four crucial states were home to 2.33 million manufacturing jobs, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. By July 2018, a few months after Trump launched its tariffs on steel and aluminum and the same month the White House announced its first round of tariffs against Chinese-made goods, the number of manufacturing jobs in those four states had climbed to 2.38 million.

In February 2020, the last full month before the pandemic struck America, those same four states reported nearly exactly the same total: 2.38 million manufacturing jobs. Over the course of those 20 months from July 2018 through February 2020, the number of manufacturing jobs in Michigan declined by about 40,000, while the other three states reported small gains.

The story is similar across the rest of the country: From mid-2018 through the first two months of 2020, manufacturing job growth has been effectively flat after nearly a decade of consistent if unspectacular pre-trade-war growth. The tariffs that were supposed to revitalize American manufacturing instead caused a lost year.

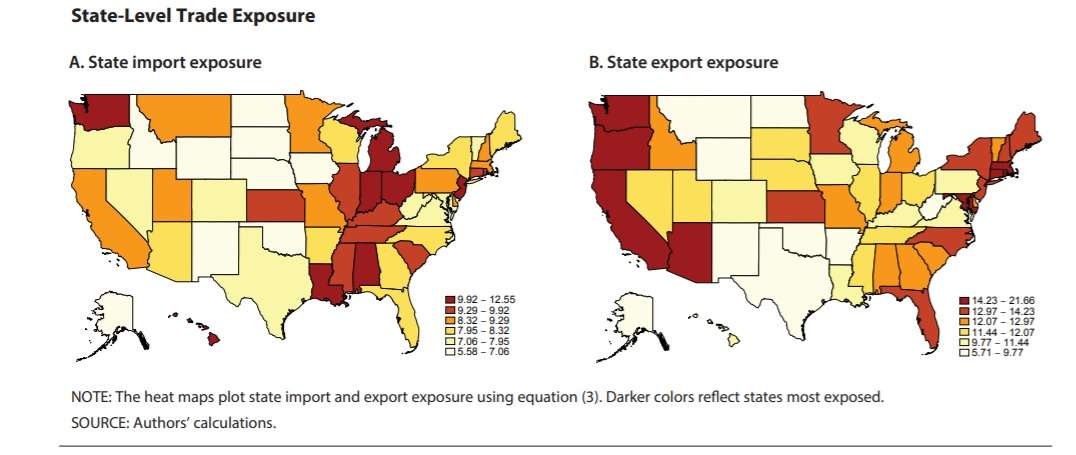

Dig deeper, and it becomes even more clear that the Rust Belt paid an outsized price for Trump's trade policies. A new study from the St. Louis Federal Reserve looks at how "exposed" each of the 50 states is to disruptions in global trade—that is, which states have industries most dependant on importing industrial components, for example, or exporting farm goods.

Unsurprisingly, the report concludes that "states that were more exposed to trade with the world have performed worse [during the trade war] in terms of employment and output growth than have states that were less exposed." Among the worst-hit states are Michigan and Ohio.

The trade war has also coincided with a flat-lining of domestic business investment, as Trump's tariffs have taken a bite out of companies' bottom lines. "Increasing tariffs also creates greater economic uncertainty, potentially dampening business investment and creating a further drag on growth," warned the Congressional Research Service in a report published earlier this year. Overall, the tariffs have had a "negative aggregate effect on the U.S. manufacturing sector," the report found, as the economic benefits of increased protectionism were overwhelmed by increased input costs created by the tariffs.

The steel industry, which was supposed to be a prime beneficiary of Trump's trade policies, is facing a "dim future" as job growth vanishes and price slump, The Wall Street Journal reported last week.

None of this surprised the vast majority of economists, who already knew that tariffs are "costly, ineffective and politically messy," writes Scott Lincicome, a senior fellow in economic studies with the libertarian Cato Institute, in a thorough run-down of Trump's trade failures in The Dispatch.

Yet Trump has vowed to keep his tariffs in place if he wins a second term, and he has bragged on the campaign trail and in debates about the "billions and billions" of dollars the federal government has collected in tariff revenue—most of which has been doled out to farmers harmed by other aspects of Trump's trade war.

On Thursday, Navarro told MSNBC that he sees the upper Midwest as "the Trump Prosperity Belt." And on Monday night, Trump will once again visit Grand Rapids, Michigan, for his final campaign rally before Election Day.

If the vote turns out differently this time around, Trump should blame his own economic policies. Rust Belt voters gave Trump the chance to do what he wanted to do—but the trade barriers that were supposed to resurrect American manufacturing have done more harm than good.

Show Comments (71)