Nixon May Be Trump's 'Law and Order' Model, but He Was Smarter on Crime

He did not overpromise, and he had the good sense to stop talking about a country beset by violence when he ran for a second term.

Donald Trump consciously modeled his 2016 presidential campaign on Richard Nixon's in 1968, presenting himself as "the law and order candidate" who would eliminate the "violence in our streets and the chaos in our communities," despite historically low crime rates. But while Nixon recognized that continuing to describe the country as unsafe and crime-ridden while seeking a second term would not reflect well on his own performance in office, Trump still sounds like a harsher, less eloquent, and less subtle version of the 1968 Nixon.

By 1972, Nixon had stopped talking about a country beset by violence, notwithstanding a substantial increase in crime during his first term. Trump, by contrast, is still hitting that theme, notwithstanding a decrease in crime.

In 2016, Trump promised that "the crime and violence that today afflicts our nation will soon come to an end" and that "beginning on January 20, 2017, safety will be restored." In his inaugural address six months later, he vowed, "This American carnage stops right here and stops right now." Now he is trying to get re-elected by decrying the "rioting, looting, arson and violence" happening on his watch.

Trump tries to gloss over the contradiction between his pledges and the chaotic situation he is still describing four years later by blaming the latter on bad governance in "Democrat-run cities." He thereby emphasizes that the president has no power over local policing, which makes both the extravagant promises he made in 2016 and the contrast he is trying to draw now with Joe Biden look pretty silly.

"Your vote will decide whether we protect law-abiding Americans, or whether we give free rein to violent anarchists, agitators, and criminals who threaten our citizens," Trump said while accepting his party's nomination last night. "If you give power to Joe Biden, the radical left will defund police departments all across America. They will pass federal legislation to reduce law enforcement nationwide. They will make every city look like Democrat-run Portland, Oregon. No one will be safe in Biden's America."

Trump did not explain how Biden would "defund police departments," how Congress would "reduce law enforcement nationwide," or how either would turn "every city" into a Portland-esque hellscape. If Trump, by his own account, is powerless as president to stop the "violence and danger in the streets of many Democrat-run cities throughout America," how would Biden as president make the situation worse?

Nixon in 1968, like Trump in 2016, exaggerated the federal government's role in fighting crime, a perennial habit of national politicians. But during a year more turbulent than 2016 or even 2020, he was still careful not to make any commitments regarding public safety and order that would be impossible to keep.

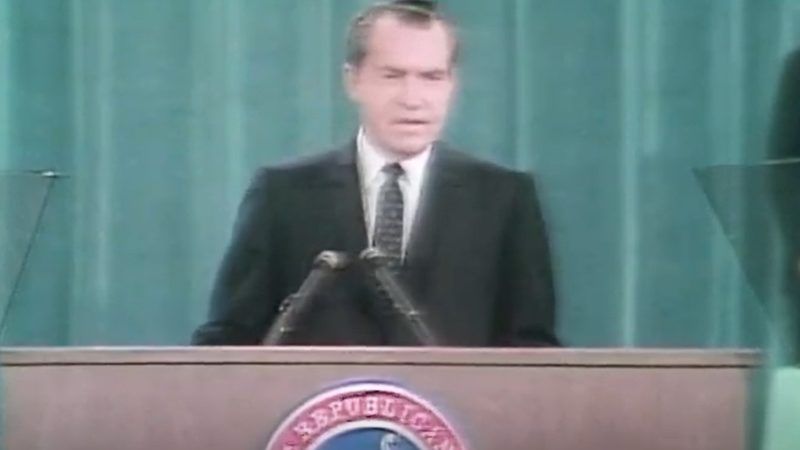

"As we look at America, we see cities enveloped in smoke and flame," Nixon said in his acceptance speech. "We hear sirens in the night….We see Americans hating each other, fighting each other, killing each other."

What did Nixon propose to do about it? "Tonight I do not promise the millennium in the morning," Nixon said in a passage the Trump and his speechwriters must have missed. "I don't promise that we can eradicate poverty, and end discrimination, eliminate all danger of war in the space of four, or even eight, years. But I do promise action—a new policy for peace abroad; a new policy for peace and progress and justice at home."

Regarding domestic peace and justice, Nixon promised to appoint judges who would be friendlier to law enforcement. "Let us always respect, as I do, our courts and those who serve on them," he said, expressing a sentiment foreign to Trump. "But let us also recognize that some of our courts in their decisions have gone too far in weakening the peace forces as against the criminal forces in this country, and we must act to restore that balance."

Nixon also promised to appoint an attorney general who would "launch a war against organized crime in this country." That attorney general, he said, "will be an active belligerent against the loan sharks and the numbers racketeers that rob the urban poor in our cities." He would "open a new front against the filth peddlers and the narcotics peddlers who are corrupting the lives of the children of this country." Nixon's most extravagant promise was that "time is running out for the merchants of crime and corruption in American society."

In his acceptance speech four years later, Nixon said he had kept his pledge to appoint judges who "recognize that the first civil right of every American is to be free from domestic violence." He added, "I want the peace officers across America to know that they have the total backing of their president in their fight against crime." And that was pretty much it. Unlike Trump this year, Nixon was no longer depicting a country plagued by crime and violent unrest.

So far we have been talking about rhetoric. What about the corresponding realities?

In 1972, the violent crime rate in the United States was more than 25 percent higher than it was in 1968. The homicide rate had risen nearly as much. Unsurprisingly, Nixon did not mention those trends, let alone dwell on them.

From 2016 to 2018, the last year for which the FBI has released final numbers, the violent crime and homicide rates fell. While those numbers were higher than the record lows recorded in 2014, they were still down nearly 50 percent from their peaks in 1991. Preliminary FBI numbers for the first half of 2019 indicate that homicides fell again. Jeff Asher of AH Datalytics found that murders spiked in major cities during the first half of this year, although overall violent crime was down. Yet Trump is portraying a country where violence is spinning out of control, a trend he says will only get worse if Biden is elected.

On the face of it, that strategy makes little sense. But it fits with Trump's general approach to politics, which requires demonizing the opposition to scare people into voting for someone they otherwise might not find particularly appealing.

Show Comments (289)