The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Does the Democratic Platform Endorse Court-Packing?

When it comes to the Supreme Court, the answer is clearly "no." Things are less clear when it comes to the lower federal courts.

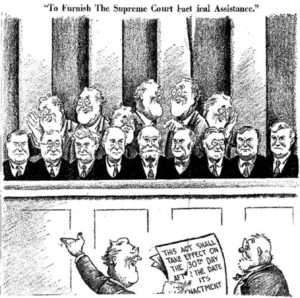

The Democratic Party recently published its 2020 platform. One issue of special interest to anyone who cares about the future of the federal courts and judicial review is whether the party would endorse court-packing. For at least two years now, some liberal activists have urged the Party to increase the size of the Supreme Court in order to appoint liberal justices to reverse the current 5-4 conservative majority on the Court, which many on the left believe was created by illegitimate means (most notably the GOP-controlled Senate's refusal to hold hearings on Barack Obama's Supreme Court nominee, Judge Merrick Garland, in 2016). If implemented, such proposals would predictably lead to a cycle of retaliation that would likely undermine judicial review as an effective check on the other branches of government (see my discussion of these issues here, here, and here).

The good news about the Democratic platform is that it does not endorse any plan to pack the Supreme Court. That includes not only straightforward increases in the number of justices, but also such workarounds as "rotation" of justices (advocated by Bernie Sanders during the Democratic primaries).

Before the Democratic Convention, news reports suggested that the Democrats would embrace "structural change"of the federal courts. When it comes to the Supreme Court, they clearly have not done so. Perhaps the Party was influenced by the Court's growing popularity, which would make a confrontation with the justices politically dangerous. Alternatively, they might have been swayed by presidential nominee Joe Biden's own previously stated opposition to court-packing. Either way, the the Democrats have - so far at least - shied away from efforts to pack the Supreme Court.

Things are less clear when it comes to the lower federal courts. Here, the Democratic Platform says the following:

Since 1990, the United States has grown by one-third, the number of cases in federal district courts has increased by 38 percent, federal circuit court filings have risen by 40 percent, and federal cases involving a felony defendant are up 60 percent, but we have not expanded the federal judiciary to reflect this reality in nearly 30 years. Democrats will commit to creating new federal district and circuit judgeships consistent with recommendations from the Judicial Conference.

Conservative activist Carrie Severino and my co-blogger Randy Barnett denounce this as court-packing. By contrast, prominent left-wing legal commentator Ian Millheiser sees it as a "timid" plan that "will do little to counter the GOP's grip on the federal bench."

Who is right? The truth is not easy to discern, but probably lies somewhere in between.

If we take the rationale for the Democratic proposal at face value, it is not court-packing at all. The latter is not simply expanding the number of judges, but doing so for the purpose of changing the ideological balance on the court in question. Otherwise, every increase in the number of judges throughout the history of the United States (of which there have been many) would qualify as "court packing."

The Democratic platform justifies its proposed expansion by citing growing case loads, and also assures us that any increases will be "consistent with recommendations from the Judicial Conference [of the United States]." The Judicial Conference is the policymaking body of the federal judiciary, and includes representatives from the Supreme Court all of the various courts of appeals and district courts. If the Democrats stick to its recommendations, they can argue they are not pursuing a partisan court-packing agenda, but merely following the advice of a politically neutral body, which includes both liberal and conservative judges.

The Judicial Conference, has in fact recommended only a modest expansion of the judiciary, using much the same case-load rationale as that presented by the Democrats. Here is what the Conference says on its website:

The Judicial Conference has recommended that Congress establish five new judgeships in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals and 65 new judgeships in 24 district courts across the country. The conference also recommended that eight existing temporary district court judgeships be converted to permanent status.

Since 1990, when the last comprehensive judgeship bill was passed by Congress, case filings in the courts of appeals had grown by 15 percent by the end of 2018, while district court case filings had risen by 39 percent in the same period.

"The effects of caseload increases without increasing the number of judges are profound," [Judge] Miller said in his written testimony. "Increasing caseloads lead to significant delays in the consideration of cases, especially civil cases which may take years to get to trial. … Delays increase expenses for civil litigants and may increase the length of time criminal defendants are held pending trial. Substantial delays lead to lack of respect for the Judiciary and the judicial process."

The full text Judge Miller's recent testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee is available here. Current law provides for 179 court of appeals judges, and 663 federal district judges (including 10 temporary appointments). The Judicial Conference plan would increase the numbers of the former by less than 3%, and the latter by about 10% (or slightly more than that, if you include the eight temporary judgeships converted to permanent ones). Moreover, the vast majority of the new judges will be district judges. They have less discretionary authority than appellate judges, and their decisions are not considered binding precedents (though they often do influence later rulings, nonetheless). A massive court-packing revolution this is not.

The modest scale of the proposal is what leads Millhiser to call it "timid" and inadequate. But it is still far from totally insignificant. Appointing five new judges to the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit would ensure a strong liberal majority on an important appellate court that covers California and numerous other western states. The Ninth Circuit's jurisdiction applies to more people than any other federal regional appellate court.

In addition, only very naive observers are likely to believe that concerns about judicial caseloads and deference to the expertise of the Judicial Conference are the only - or even the most important - motivations for the Democratic proposal. After all, that proposal comes in the same section of the platform where the Party laments the GOP's appointment of numerous conservative judges, and promises to appoint Supreme Court justices who will be committed to liberal results on various key issues within the purview of the courts, including abortion.

In this context, we should remember that past court-packing proposals also often came packaged with rationales emphasizing "neutral" factors such as managing caseloads. The official rationale for Franklin D. Roosevelt's 1937 plan to pack the Supreme Court was the need to ease the workload of elderly Supreme Court justices (thus it was structured to allow the president to appoint one new justice for each current one who had reached the age of 70.5 years but chose not to retire).

The Democratic platform proposal reminds both me and Millhiser of the 2017 plan for Republicans to pack the lower courts proposed by prominent conservative law professor Steve Calabresi and his coauthor Shams Hirji (as Millhiser notes, I strongly opposed the plan at the time). The memo outlining Calabresi-Hirji proposal also offered justifications based on the need to deal with growing case loads (which took up most of the space in their text), though they let the cat out of the bag when they stated that one of their goals is "Undoing President Barack Obama's Judicial Legacy."

Unfortunately, I cannot link to the Calabresi-Hirji article because the the controversy caused by the proposal eventually led the authors to remove the piece from SSRN, and it has never been revised and reposted since then [UPDATE: a copy of the paper is still available here]. But other veterans of the debate over their piece can confirm my recollections of its content.

As Millhiser notes, one key difference between the Democratic platform proposal and the Calabresi-Hirji plan is the much greater scope of the latter. Calabresi and Hirji called for 61 new federal appellate circuit court judges (36% more than the current number), and 200 new district court judges (almost 30% more than the status quo). They also argued that Congress should replace 158 administrative law judges currently selected by executive branch administrative agencies with standard life-tenured judges appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate. But this very significant difference in degree is not the same as a difference kind. Moreover, if case loads continue to increase (or perhaps even if they don't), the Democrats could easily say that we actually need more new judges than the Judicial Conference advocates.

If the Democrats go through with their plan, Republicans and others might well (with good reason) assume that court-packing is a large part of the motivation. They might then retaliate in kind as soon as they have the opportunity to do so. When he rejected proposals to pack the Supreme Court, Joe Biden pointed out that "We add three justices. Next time around, we lose control, they add three justices. We begin to lose any credibility the court has at all." The end result would be the neutering of judicial review, as any ruling that seriously impedes one party's policies would predictably be met by "packing" of the court in question. The same dynamic could occur with federal lower courts.

Millhiser may well be right in this warning:

Republicans are likely to attack any Democratic proposal to increase the size of the federal judiciary as if it were akin to Calabresi-style court-packing.

Once Republicans have convinced themselves that Democrats broke the seal on court-packing, they are likely to find something like Calabresi's proposal much more palatable in the future.

Democrats, in other words, appear to have stumbled into a dangerous middle ground, at least as far as the proposal in the platform goes. They've proposed a policy that is simultaneously bold enough that it is likely to trigger Republican retaliation, but milquetoast enough that it will do little to counter the GOP's grip on the federal bench.

A court-packing war over the lower federal courts might be almost as damaging as a similar conflict over the Supreme Court. As a practical matter, lower courts decide the vast majority of cases. Only a tiny fraction ever reach the Supreme Court (though many that do are unusually important ones). Effective judicial review requires engagement by the lower courts, not just Supreme Court justices. Collectively, the former may actually have more influence than the latter, though any one SCOTUS justice obviously has far greater clout than any one lower court judge.

That said, the relatively limited nature of the Democratic platform proposal does reduce the risk of a court-packing tit for tat relative to either a plan to pack the Supreme Court or a full-blown Democratic version of the Calabresi-Hirji plan.

If the Democrats really are serious about limiting themselves to politically neutral adjustments to deal with rising case loads, they can address that problem in ways that more clearly avoid court-packing. One would be to institute the new judgeships on a staggered schedule over time. For example, one-third of the new judgeships recommended by the Judicial Conference could be instituted immediately (say in 2021 or 2022), one-third in 2025 (after an intervening presidential election), and one-third in 2027 (after an additional intervening congressional election). That would ensure that many of the new judgeships will take effect only at a time when we cannot currently predict who will be in power.

Of course, if the 2020 election ushers in a lengthy period of Democratic dominance of the presidency and Congress, they will ultimately get to fill all the new judgeships. But in that event, the Democrats will be able to gradually take control over lower federal courts anyway, through the normal process of attrition and replacement.

A staggered approach might be dangerous if the federal courts really were facing a crisis so great that they cannot resolve the cases before them without major immediate reinforcements. But that does not seem to be the case. As prominent conservative court of appeals Judge William Pryor put it in an op ed criticizing the Calabresi-Hirji plan:

If judges were overworked and cutting corners, they would undoubtedly ask Congress for more help beyond filling vacancies and the addition of a modest number of judgeships requested annually. If federal courts were suffering a caseload crisis, there would be nothing attractive about being a federal judge, and judges would be departing in droves. And they're not.

Perhaps federal courts could use some reinforcements. But there is no imminent crisis requiring immediate expansion of the number of lower court judges. Thus, a staggered plan could help alleviate case load pressures, while simultaneously minimizing the risks of court-packing.

I'm not necessarily wedded to the staggered approach. There may be other ways of achieving that same goal. The key, however, is to make sure that any proposal to increase the size of the federal courts really is a nonpartisan plan to address case load issues or other similar problems, not a thinly veiled push for court-packing.

The Democratic platform is unlikely to be the end of the current round of debates over court-packing. If Biden wins the election, he may not follow all of the platform's recommendations. But the text is a good indication of where the party's leaders currently stand. I'm happy that they chose not to endorse packing of the Supreme Court. When it comes to the lower courts, things are more ambiguous. The proposal the party endorsed is relatively modest. But it still creates some risk of escalatory retaliation, if implemented.

Obviously, those who believe court-packing is justified as a means of retaliation for GOP misdeeds, or that judicial review really should be neutered are unlikely to share my concerns. I do not have the space to address these positions in detail here. This post is probably too long already!

But I have done so in earlier writings, such as here, (explaining why court-packing would be a dangerous escalation, not just retaliation in kind), here (explaining why there is good reason to fear court-packing even if you don't like many of the decisions of the current SCOTUS majority), and here. For those who worry about the potential deterioration of liberal democracy in the US, the liberal Vox site has a good discussion of court-packing is a standard tool of authoritarian populists seeking to undermine liberal democracy, recently used in such countries as Hungary, Turkey, and Venezuela.

UPDATE: The 2017 Calabresi-Hirji paper referenced in the post is still available here.

Show Comments (69)