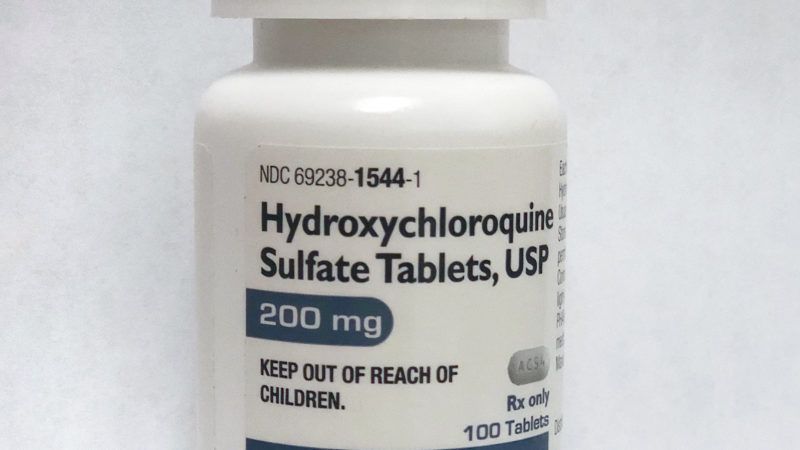

White House Recommends Against Grocery and Pharmacy Trips While Trump Says Go Ahead and Try Hydroxychloroquine

Plus: shutdown suits, the pantry police, and more...

Stay really, really at home now? On Saturday, White House coronavirus response coordinator Deborah Birx said of the next two weeks: "This is the moment to not be going to the grocery store, not going to the pharmacy, but doing everything you can to keep your family and your friends safe."

Yikes. Keeping safe now means avoiding shopping for even food, toiletries, and medicine? No wonder President Donald Trump has been hoping so hard for hydroxychloroquine to work against COVID-19.

But Trump advisor and infectious disease expert Anthony Fauci isn't so sure about the anti-malarial drug as a cure for the new coronavirus. In a meeting Saturday, "Fauci pushed back against [economic adviser Peter] Navarro, saying that there was only anecdotal evidence" for it, reports Jonathan Swan at Axios. More:

Eventually, [Jared] Kushner turned to Navarro and said, "Peter, take yes for an answer," because most everyone agreed, by that time, it was important to surge the supply of the drug to hot zones.

The principals agreed that the administration's public stance should be that the decision to use the drug is between doctors and patients.

Trump ended up announcing at his press conference that he had 29 million doses of hydroxychloroquine in the Strategic National Stockpile.

One thing driving this may be a desire not to drop the ball again on COVID-19 prep, as the administration has already done with tests, masks, and ventilators. Not that Trump will admit his team has faltered in the slightest. He's spent the past week bragging about how big his backup of medical supplies is, while simultaneously declaring this Strategic National Stockpile mostly off-limits to American states.

The president now regularly describes the supply of ventilators and masks in terms of negotiations he allegedly made well and states didn't, making this into a competition where there should be cooperation to save lives.

Last week—after Trump advisor and son-in-law Jared Kushner called it "our" stockpile at press conference ("our" meaning the federal government, Trump clarified) and Trump scoffed at states like New York for lacking supplies—the language on the Strategic National Stockpile's website was changed:

But while Trump has been bashing state leaders for not stocking up pre-pandemic, the federal government waited until mid-March to bolster its supplies, according to a new report from the Associated Press. AP's review of federal purchases "shows federal agencies largely waited until mid-March to begin placing bulk orders of N95 respirator masks, mechanical ventilators and other equipment needed by front-line health care workers."

By the time these agencies were starting to place orders, "hospitals in several states were treating thousands of infected patients without adequate equipment and were pleading for shipments from the Strategic National Stockpile," AP reports. The stockpile is "now nearly drained."

If hydroxychloroquine may be useful, it's not unreasonable for Trump to want to get an early jump on that. ("If it does work, it would be a shame we did not do it early," as Trump said on Saturday.) And Trump's underlying rhetoric about people and hospitals having the right to decide for themselves about experimental cures is also sound. ("It's their choice. And it's their doctor's choice," Trump said Saturday.) It has a lot in common with more general arguments for "right to try" laws—but with a critical difference, too.

Right-to-try advocates generally argue that when specific people are dying from diseases that can't be cured by treatments the Food and Drug Administration has approved, they should be able to try experimental drugs, generally ones that have proved promising in clinical trials or are already approved in other countries. They don't generally push for masses of patients to try barely tested and potentially risky cures for communicable diseases on a whim or a hunch.

So far, the case for hydroxychloroquine amounts to little more than a handful of studies with no control patients and a report from Chinese doctors posted to a non-peer-reviewed website. The Chinese doctors said that in a small sample of patients with mild to moderate cases of COVID-19, hydroxychloroquine seemed to help fevers and pneumonia dissipate faster and may have helped stop cases from turning more severe. It was not tested on severe or asymptomatic cases.

Another recent study found "no evidence" of hydroxycholorquine helping patients with severe COVID-19 infections.

All that said, it's certainly preferable that doctors can try treating patients with hydroxychloroquine without federal bureaucrats saying they must wait until we've done years of trials.

"With no proven treatment for the coronavirus, many hospitals have simply been giving hydroxychloroquine to patients, reasoning that it might help and probably will not hurt, because it is relatively safe," notes The New York Times.

But some doctors note that while hydroxychloroquine may be relatively safe, it's far from harmless. "There are side effects to hydroxychloroquine," Brown University emergency physician Megan L. Ranney told the Times. "It causes psychiatric symptoms, cardiac problems and a host of other bad side effects."

FREE MARKETS

Against pantry policing. Shaming people for their pandemic-time purchases has become a new national pastime. At Arc Digital, Phoebe Maltz Bovy takes a calm look at how people are responding to the fact that "slowly yet suddenly, everything changed":

Human activity has been divided into the essential and the inessential, with breathing falling into the former category (as long as there are ventilators available, at least) and just about everything else, the latter. Office jobs, clothes-shopping, bar-going, sex (or just in-person conversation) with anyone you don't happen to live with—all of these everyday pursuits have been put on hold, their eventual return uncertain.

Falling somewhere ambiguous between necessity and frivolity, however, is food. On the one hand, we've all got to eat. On the other, the discourse about eating in the era of coronavirus has a way of suggesting food is a luxury, a pseudo-requirement the more noble among us would somehow transcend. As though if you believe yourself and your family entitled to food, now and in the foreseeable future, then you're exhibiting a level of unacceptable entitlement….

A figure has emerged of the Bad Grocery-Shopper, the proverbial Karen who buys more than is correct (even though, and I cannot emphasize this enough, no one knows or can know what "correct" would mean), and who is definitely, definitely buying toilet paper in excess. Indifferent to the fate of her local businesses (or, perhaps, newly unemployed herself?), she isn't even sending a few bucks here and there to her preferred bars and cafés. The problem isn't coronavirus; it is—it's soothing to think, apparently—middle-aged, middle-class women buying groceries for their families.

Read the whole thing here.

FREE MINDS

Businesses are beginning to sue over mandatory shutdown orders. From The New York Times:

Some of those suing their state governments seek redress for specific, local grievances, as with the [Blueberry Hill Public Golf Course and Lounge lawsuit] or in a similar suit in Pennsylvania being pursued by a company that says it is the country's oldest manufacturer of orchestra-quality bells and chimes. Those lawsuits and one in Arizona are rooted in the Fifth Amendment, which requires due process and guarantees compensation for property seized by the government.

Other constitutional amendments have been invoked in several lawsuits in recent weeks attempting to force open gun stores, or to argue that measures to curb the virus should not outweigh rights like freedom of assembly and religion.

"Those may be serious, but they may also be part of an attempt to make an argument in the press about overreach," said Tom Burke, a political-science professor at Wellesley College who studies the politics of litigation.

History dating back to the time of 15th-century plagues shows that lawsuits typically plummet during pandemics, Mr. Burke said, for the obvious reason that courts are closed. But legal experts anticipate a tidal wave of court activity afterward—especially in fields like insurance and debt collection—because of the economic dislocation caused by the pandemic.

More here.

QUICK HITS

- A tiger at the Bronx Zoo has COVID-19.

- People in Kentucky who violate self-isolation orders are being forced to wear ankle monitors.

- Supreme Court update: "Following postponement of arguments scheduled for the last two weeks of March, the court on Friday announced that it would delay another round of oral arguments—its last for the term—scheduled for the second half of April," reports NPR.

- COVID-19 deaths in the area around New Orleans are drastically outpacing those in New York City. The former has 37.93 per 100,000 people, and the latter 18.86 per 100,000 people, per Johns Hopkins University figures and a Wall Street Journal analysis. Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards attributed the high death rate to the state having "more than our fair share of people who have the comorbidities that make them especially vulnerable."

- States across the South could see similar situations to Louisiana, argues Margaret Renkl, who lives in Nashville.

- America has now seen nearly 10,000 deaths from COVID-19.

- We're all guinea pigs in a pandemic:

We get it, we're in the simulation https://t.co/FL8aUjX84W

— Benjy Sarlin (@BenjySarlin) April 4, 2020

- "One of the many things revealed by the political response to the coronavirus pandemic," writes Nick Gillespie, is "that there are very few meaningful differences between the Republicans and Democrats."

- Corona suspending production.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

This is the moment to not be going to the grocery store...

Simply pluck the vegetables out of your backyard garden and hunt for game.

As long as you are only hunting game with a club, or perhaps a bow and arrow, but certainly NOT with a gun!

Change Your Life Right Now! Work From Comfort Of Your Home And Receive Your First Paycheck Within A Week. No Experience Needed, No Boss Over Your Shoulder… Say Goodbye To Your Old Job! Limited Number Of Spots Open…

Find out how HERE…….. http://www.WORKS66.com

You've changed, man.

You've changed

LOL

Better not have more than 10 people in your hunting club.

("I once killed a lion with a club...")

I once killed a bengal tiger with a banana.

Hello.

The UN names China to the Human Rights panel.

During a pandemic.

I'm at this point at a loss for words trying to convey how angry I'm feeling.

Make that: During a pandemic started in China and subsequently covered up by Chinese lies that put the entire world in danger.

So the UN's response? 'Hey, let's give them a seat!'

Maybe the Chinese government (and the UN) interpret the Human Rights panel in a different way, like the idea that they should have the right to humans.

You forgot and now selling supplies at markup to profiteer off the pandemic they started, much of the goods defective.

Accidental flag announced

I blame China for the pop up vids now

Makes sense when you look at all other scum who have held a seat on UN Human Rights council. Libya, Sudan and Venezuela are other esteemed members. They always include some of the worst countries.

They once had Robert Mugabe as a 'Good will ambassador'.

This is the United Nations. A lawless, corrupted, morally bankrupted cess pool of degenerates.

No wonder Justin loves it.

It's Diversity, Rufus. Multiple points of view make us stronger.

This is the moment to not be going to the grocery store…

and we get second round of panic buying and hording, thanks you government.

about vegetable i see some states are claiming garden supplies as non essential. they really do not want us to be able to fend for ourselves. Of course when the people can they realize they don't need as much government

i see some states are claiming garden supplies as non essential

They can have my home grown tomatoes when they pry them from my cold dead hands.

thank full I have some seeds left over from last year. the local markets have been plundered by hoarders

"Let them eat cake."

With shopping for food verboten, whatever shall we do?

Shaming people for their pandemic-time purchases has become a new national pastime.

Thank God the outrage industry isn't taking a hit from the quarantine.

A tiger at the Bronx Zoo has COVID-19.

Without having seen the documentary or whatever it is, I blame the Tiger King.

I want to see the zookeepers trying to put a mask on a tiger.

Makes you wonder who got within 6ft of the tiger.

And what is left of them.

We are releasing pedophiles from jail, but dont you date fucking paddle board by yourself or you'll be arrested.

https://pjmedia.com/trending/pedophile-rapist-released-from-massachusetts-prison-to-protect-him-from-coronavirus/

That way in Houston too. A murderer got let out of jail because of Covid fear and an idiot straight-ticket Democrat judge who bought the story. Guess we get to relive the 70s all over again.

OTOH, a state district court judge stopped the planned 1,000 or so release of prisoners from the county jail, stating they had jurisdiction, not the village idiot County Judge.

Deaths are down, not just rising slower than expected; new cases are down. Let's see if Monday continues the good trend.

Where do these officials think the criminals are going to go? Are they going to find a job and start paying rent?

The black market is hiring.

The USA is not going to implode all by itself and have Americans beg for government intervention.

We need massive crime again.

We need hysterical panic.

We need to listen to the lying media again.

We need to accept the recommendations of our betters.

Is a pedophile rapist someone who rapes pedophiles? Is that really a problem?

I read somewhere that most kiddy diddlers were molested as kids themselves, so maybe.

I think those are the guys who become the boyfriends of the pedos in prison. The relationships are compulsory. Or is it cumpulsory?

The one person who has pleasantly surprised me during the Trump era has been Nick "The Jacket". Now if he could just slap some of the stupid TDS out of his younger staff, the quality of these articles would get a whole lot better.

Trump was right about China all along.

What will it take for people to treat or view China like we did the Soviet Union?

A shooting war. Which we might get in the first island chain, if Xi thinks he needs to whip up an external boogeyman to save his own ass.

No operational carriers in WestPac for the time being. Reagan has some Covid cases too, in Yokosuka. I hope Ford, and the other one I forget, complete training their replacement squadrons quickly.

While I dont think this KungFlu was a purposeful biological weapon attack, the veracity in which our treasonous media and Lefties around the World have sought to go all tyrannical is alarming. It also exposes that they are mostly being desperate and opportunistic enemies.

The fact that China is having flare ups of Wuhanvirus again, tells me that we need to be prepared for anything from these lying and opportunistic tyrants.

http://www.zerohedge.com/geopolitical/covid-19-chinas-colossal-cover

the veracity in which our treasonous media and Lefties around the World have sought to go all tyrannical is alarming. It also exposes that they are mostly being desperate and opportunistic enemies.

The truth is that the lefty New World Order "elites" have been planning out something like this for decades.

The veracity?

I'm guessing velocity. Autocorrect can be a bitch.

As Trump administration debated travel restrictions, thousands streamed in from China

Remember when Lefties fought to prevent Trump from restricting border access? I do.

Not really, since the news cycle then was Impeachment 24/7.

Biden is out there saying Trump should have issued the ban sooner.. you know back when joe was calling him a xenophobe for the ban.

Like in Canada. When people called for airport travel closures from China and Iran, the official response from Canada was that it would be 'xenophobic.'

To me. this is dereliction of duty.

The idiots do so love that word

Being a progtard requires one to accept two contradictory arguments.

People in Kentucky who violate self-isolation orders are being forced to wear ankle monitors.

If only they had this technology back when AIDS was a bigger thing. RIGHT?

How the hell do they get the ankle monitor on from six feet away?

And what sex acts are possible while keeping ankles 6 ft apart?

"Hand washing"

Another promising medicine widely produced to help kill Covid in vitro. Democratic governors and media quickly look to ban.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0166354220302011

Ivermectin is an inhibitor of the COVID-19 causative virus (SARS-CoV-2) in vitro.

A single treatment able to effect ∼5000-fold reduction in virus at 48h in cell culture.

Ivermectin is FDA-approved for parasitic infections, and therefore has a potential for repurposing.

Ivermectin is widely available, due to its inclusion on the WHO model list of essential medicines.

I wonder if all of these malaria and parasitic prophylactic medications, that are both widely used in the tropics, and appear to have some benefits against Covid, are the reason we're not seeing African countries or places like Indonesia go completely berserk with Covid?

Well, also those countries don't have a lot of old people :/

Or fatties.

Didn't read the article- has Trump mentioned that he's heard some smart people are looking at that and possibly, maybe, it would be cool if it turned out it was effective against the disease, but we have a long way to go before we know anything? Or as the media would put it, has Trump completely dreamed this up himself out of thin air and told the nation that they should absolutely go find some ASAP and take it because it will save their lives? Ivermectin is widely used in cattle and other livestock as a dewormer. Every rural farm supply store has it. The headlines about Trump telling everyone to take cow medicine practically write themselves.

Some brands of canine monthly de-wormers have Ivermectin as one of the active ingredients. I wouldn't recommend it for humans.

Navy Captain Removed From Carrier Tests Positive for Covid-19

This guy is a real scumbag. I hope the US Navy does not have a bunch of officers like this in command positions or we are fucked.

It wasn't Crozier's idea to have the port visit in Vietnam that exposed his crew. An O-6 doesn't get to tell the CSC (O-7) or the theater commander (O-10) what to do, or whether his ship will make a historic port visit or not.

I also believe that Crozier was getting soft-pedalled by the Navy, when he told them about how the virus was spreading through the ship, long before I'll believe that self-serving statement Modly sent out, justifying Crozier's relief from his position.

Finally, I'll take the word of people I know who served with him, and worked for him---all saying the guy was a top notch boss, excellent technically, and actually gave a shit about his Sailors---over someone who may have served in the Navy, but doesn't know many particulars of the incident, and has been continuously downplaying the seriousness of this virus from the very beginning.

Whoever is ultimately to blame, right now the US is down a carrier until they can disinfect the spaces, and see how much of the carrier's air wing (group?) is combat effective at the moment.

You need a citation that a Fleet Commander ordered an aircraft carrier commander to a liberty port and that all crew had to have liberty.

This while a clear KungFlu was causing problems in China/Asia.

This is like Lefties blaming Trump for not stopping flights from Asia when Trump was trying to and Lefty judges were granting injunctions to prevent such measures.

You stupid motherfucker. The head of PACOM was on the fucking dock in Da Nang greeting the ship. Along with the Ambassador of the US to Vietnam.

He. Didn't. Have. A. Choice. About. Granting. Liberty.

The Navy is covering their own assets about the idiocy of:

1, having a port visit period in a country suffering from Covid.

2. Not giving Crozier the resources he was asking for to battle the bug. The official excuse---that Guam didn't have anywhere to stash a few thousand sick sailors---is absolute horseshit. We still have Andersen AFB, don't we? Doesn't it have a golf course, as well as a gazillion other places a tent city could be placed? Don't we still have Red Horse teams and CBs? Can't they build a sufficient lodging/quarantine area in the time between hearing TR has a problem, and TR raising anchor to leave?

That is, if the USN actually took this seriously, and didn't think, 'Meh, it's just the flu, bro. Stop complaining.'

Modly is trying to save his own ass, as well as tell other combatant commanders to get ready for war soon.

If a cruise ship can keep the kungflu down to 700 people I would think a navy ship with far better medical equipment and training should be able to do better. but in recent years are navy has had a lot of f ups at sea. mainly hitting other ships they could see from miles away

I would think a navy ship with far better medical equipment and training should be able to do better

And horrible ventilation below decks, crew in constant close proximity, etc. If the ship's at sea, people are still doing their jobs and moving about the ship.

This was 100% preventable. The Navy should have all crews restricted to ship.

Yup. 700 infected out of 3700 passengers and crew shows how this virus is not automatically contagious.

The cruise ship residents were locked in their cabins, essentially. On a warship...that doesn't work as well. Not if you want the thing to be more than a 20 billion dollar target and way to shuffle Sea Sparrows around the Pacific.

You can't meaningfully conduct social isolation on a 7,000 man warship.

Obama advanced many officers like this one through the ranks during his presidency.

Progtards have to go. Period. Best to accept that now, while there is still time.

Elizabeth Warren

✔

@ewarren

· Apr 2, 2020

Our health care system is rife with racial disparities. Racial data on coronavirus will be critical to ensuring an equitable and just response to this crisis across the board.

But we don’t have that data—yet.

Data? We know by definition and a priori that everything we do is unequal and racist. It just may take a few years of academic "research" to prove it.

She does OBL better than OBL.

I lol'd

Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards attributed the high death rate to the state having "more than our fair share of people who have the comorbidities that make them especially vulnerable."

There's something to be said for a governor who knows his constituents.

And in the name of equality, more people in under-represented states should become diabetic, hypertensive, and obese. A new federal program?

Look, I know some of the idiots in here are still in denial, but the Mueller investigation was a political haranguing. Further proof? He was hiding exculpatory evidence and letting media run with conspiracy theories.

https://pjmedia.com/trending/report-mueller-hid-evidence-exonerating-don-jr-over-infamous-trump-tower-meeting/

Unfortunately for them, they will either ignore this, or will forget about it in a few days.

Birx said of the next two weeks: "This is the moment to not be going to the grocery store, not going to the pharmacy"

"And in this spirit, the Task Force Briefing will be suspended for the next two weeks."

Joe Biden Says He’s Going To Start Wearing A Mask In Public And That 2020 Convention May Need To Be Virtual, In Latest Sign Virus Is Upending Election

I bet Uncle Joe would love the entire campaign to be video from here on out. He could be auto-tuned and edited.

The Democrat Party is finished nationally. This is a hilarious train wreck. Like that guy who stopped a runaway train like .5 miles from the USNS mercy in Los Angeles.

He could be auto-tuned and edited.

"Hide ya kids, hide ya wife."

"They rapin' everyone up in here."

What's hilarious is that train wreck Biden is looking at having trainwreck Whitman join the ticket.

Gretchen Whitmer from Michigan? Oh, yeah I see that. HAHA.

So I guess Hillary is out of the running.

She is if Biden doesn't have a deathwish.

Hillary was never in the running. Without even looking, I'm sure her negatives are even higher than Trump's by now.

Whitmer isn't a bad strategic choice, as she would probably lock in Michigan, one of the states which narrowly went to Trump in 2016, much to the surprise of many pundits. I doubt she could bring in more of the woke white female vote than Harris, but I haven't seen any polling numbers for her.

Of course Michigan is getting hammered. Actually, not really Michigan, but certain areas (you can guess where). The vast, vast majority of the state has nothing. It's telling that among progressives (and authoritarians generally), for political leaders in this, the more of your people get sick and die, the more you should be looked up to and respected. ESPECIALLY if you lock them all in their houses indefinitely before they get sick and die. The more your draconian measures don't work, the better you look in their mind. It's like that "report card" last week where they graded states on how well their populations "complied" with movement restrictions. New York, which by itself has more cases and deaths than the majority of nations on Earth, gets an A-, while Wyoming, which has like 200 cases and 0 deaths, gets an F. Obviously populations and density have almost everything to do with the disparity in the impact of Wuhan Virus between those states, but the point is that no one cares how effective any measures are for a given area, just that they are being done. If half your population dies but everyone is locked up while it happens, you are lauded as a proactive, decisive leader who listens to experts. If almost no one dies, but you let everyone go about their lives the whole time, you are reckless and selfish and sociopathic.

I figured it would be Stacy Abrams.

I'd like to get hands with her

Handsy

A Biden-bot?

If Joe uses a mask then they can do voice over with someone who knows what they are saying instead of every time he talks its " look here what you have to do" and then rambles on about something else

May e they can hire Tom Hardy to do His voice like Bane in ‘The Dark Knight Rises’.

States across the South could see similar situations to Louisiana, argues Margaret Renkl, who lives in Nashville.

Evaluating one-size-fits-all solutions is partisan.

Loeffler reports more stock sales, denies wrongdoing

Welcome to Oregon, where Antifa can assault and threaten you and then runt to the courts when you defend yourself to strip you of your first and second amendment rights.

https://pjmedia.com/trending/oregon-court-affirms-conviction-of-journalist-who-pulled-gun-to-stop-advancing-antifa-mob/

More reason the progressives have to go.

This is exactly the right time to talk about issues like reparations for slavery. My favorite Congressperson AOC explains:

COVID deaths are disproportionately spiking in Black + Brown communities. Why? Because the chronic toll of redlining, environmental racism, wealth gap, etc. ARE underlying health conditions. Inequality is a comorbidity. COVID relief should be drafted with a lens of reparations.

#LibertariansForAOC

#LibertariansForReparations

But slavery is a form of social distancing, right?

"This is the moment to not be going to the grocery store, not going to the pharmacy, but doing everything you can to keep your family and your friends safe."

Well, bad news; I consider feeding my family a significant part of keeping them safe.

So you shop for food the same way NY shops for ventilators?

No. I choose to go into a grocery store, try not to touch the parts of the cart where an employee has improperly attempted to "sanitize", but has actually just evenly distributed the germs, pick up the stuff on my list (less any paper products, of course) and pay for it.

From what I read (and suspect as not completely true) NY shops for ventilators with a gun, having attempted to be sure no one else has a gun.

What Happens If You’re Seriously Ill and It’s Not From Covid-19?

Go to a rural hospital. Many rural hospitals have zero KungFlu patients and are hurting for their normal flow of regular customers.

True, at least for the ones I have second-hand knowledge of.

"No wonder President Donald Trump has been hoping so hard for hydroxychloroquine to work against COVID-19."

Lol. Fuck off ENB. Everyone should be hoping it helps you piece of shit.

"One thing driving this may be a desire not to drop the ball again on COVID-19 prep, as the administration has already done with tests, masks, and ventilators"

I mean fuck tru.o for using all the masks in 2009 and not replacing them. What the fuck was he thinking?!? Fuck him for making governors dependent on FEMA and forcing governors to not prepare for their own emergencies. Fuck trump right ENB?

"He's spent the past week bragging about how big his backup of medical supplies is, while simultaneously declaring this Strategic National Stockpile mostly off-limits to American states."

I mean this is a good take of you dont listen to Cuomo or Newsome. Even half Whitman came out and said she was getting supplies.

You're fucking terrible ENB

"America has now seen nearly 10,000 deaths from COVID-19."

1/3rd of the way to the seasonal flu deaths. Keep praying ENB.

She is a living dunce cap.

I wouldn’t waste my time on this website except for the comments.

The CDC gives a range of 12,000-61,000 and average of 34,000 for the past decade.

For a perspective:

In 2016, the CDC reported 623,471 abortions

Who gives a shit? The abortions were the mother's choice. Dying in her own mucus isn't.

Abortion up to viability of the fetus is legal, and is going to be, no matter how much it chaps your ass. Go shoot up an abortion clinic---not that any are open right now---if you feel that strongly about it. If indeed, it is murder.

Truthfully, libertarians should be for it. Not like those babies they'd be raising, would be pro-libertarian.

Here's the most important passage from ENB's source that she ignored while cherrypicking the article for OrangeManBad fodder;

""What do you have to lose? Take it," the president said in a White House briefing on Saturday. "I really think they should take it. But it's their choice. And it's their doctor's choice or the doctors in the hospital. But hydroxychloroquine. Try it, if you'd like."

So the whole conversation she takes her quote from is about allowing the patients and their doctors to choose the treatment if they want, but that's not what ENB insinuates.

Such shitty 'journalism'.

"One thing driving this may be a desire not to drop the ball again on COVID-19 prep, as the administration has already done with tests, masks, and ventilators."

Huh?

If a tree falls in the forest (and it can't be blamed on President Trump somehow), then whether it makes a sound or not doesn't even matter. If the tree falling can be blamed on President Trump, then you've got your lead story for the day!

LOL

A snippet from the email broadcast by Matt Taibbi today.

A quick note on why independent journalism is needed more than ever:

As I wrote about in Hate Inc., the news business in America has for some time been cleaved into two groups. Roughly speaking, commercial news outlets are right-leaning or “left”-leaning. I put “left” in quotation marks because the orientation of outlets like MSNBC or the Washington Post is not really “left” but “aligned with the Democratic Party,” not the same thing.

This dynamic accelerated in recent years. Because Donald Trump is central to the marketing strategies of most outlets – MSNBC crafts news for Trump haters, Fox for the MAGA set, etc. – political reporting is mostly shaded in pro- or anti-Trump directions. When breaking stories happen (the assassination of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi is just one example) outlets scramble in the first moments to find pro- or anti-Trump angles, because audiences have been trained to look for them.

I have little doubt that average registered Democrat voters are further to the center than average journalists, these days, and I think that will prove to be a big problem for the Democratic party come November.

If you watch the Dean Scream video on YouTube, it's hard to see why that had such a big impact and, basically, knocked him out of the race. It made him look weird, out of touch, and bizarre. The Democrats didn't want that to be the face of the party--for fear they'd lose.

The thing is, since people have come to associate the news media with the Democratic party, nowadays, it's like the face of the Democratic party is doing a Dean Scream every day on national television. The news media is making the Democratic party seem weird and bizarre and out of touch--even to the center of their own registered voters.

Pelosi and Biden need to find a way to distance themselves from the news media, and I don't know how they can do that. It's not like they're about to stop covering Trump that way in an election year, and like a lot of the trolls here in comments at Hit & Run, they don't realize they're trolls. They think what they're doing is normal and everyone's just being mean to them.

HYEAAAHHGGHHH!

Nailed the spelling on that

If you watch the Dean Scream video on YouTube, it’s hard to see why that had such a big impact and, basically, knocked him out of the race. It made him look weird, out of touch, and bizarre. The Democrats didn’t want that to be the face of the party–for fear they’d lose.

In hindsight, the DNC probably used that as the excuse they needed to crowbar him out of the race, offering him the DNC chairmanship as a consolation prize. I didn't actually watch the incident until about four or five years after it happened, and my reaction was, "Really? His numbers tanked over THAT?" Probably should have been the first indication that the DNC employs a selection rather than an election process in picking presidential candidates.

The Coronavirus Pandemic Will Forever Alter the World Order

NEW New World Order?

I wish these fucking neocons like Henry A. Kissinger would just die already. These people fuck up the World and dont get the clue how bad they fucked it up.

new new new world order

4 life!

I prefer an even newer world order where marxists are a hunted, endangered species.

America has now seen nearly 10,000 deaths from COVID-19.

0.003% of the population? That can't be right.

Stop it with your mathsplaining.

But they were boomer's. Worth 100x any other generation.

Yup. Much more tragic when some 85 year old with near-terminal heart disease and emphysema dies compared to a random pre-teen. But panic on!

The boomers are in control and protecting their own.

Boomers still have decades of damage to do before they finally free this World of the horrible pain they have caused.

Not all, but there are some truly horrible Boomers who want to steal, control, and destroy.

Yeah, some say that the hysteria and fear is because this is a "boomer virus" and they are protecting themselves, but only the oldest boomers are on the margins of being in the highest risk group. Basically, this is hitting anyone who is older than a boomer (the remnants of the Greatest Generation and the Silent Generation). I have no doubt that the boomers are driving this, but they really don't have all THAT much to fear yet. Just wait a few more years when stuff like this that routinely kills old people starts hitting the heart of the boomer generation born in the 50s. They will lose their shit. Hopefully all the other idiots in society catch on to the BS by then and tell them to shut up and stay home if they are worried about their meaningless, soulless lives coming to an end.

A tiger at the Bronx Zoo has COVID-19.

If the virus spreads into the feral cat community what would TPTB do?

Thought it was a couple of their tigers and lions that tested positive? Also, can't the bug reside within Felis cattus, without the cat getting sick from it?

Though the zoo animals got diagnosed because of listlessness and dry unproductive coughing, so I guess at least the big cats can be affected by the virus.

I want to know why NYC is wasting tests on animals instead of humans? Are they a different kind of testing kits? But then why spend time developing animal testing kits? Is their a good reason to test the animals because of mutations or something I am missing? To me it just seems like a waste of resources while NYC needs everything it can for the humans.

I think it's a totally different test w/ a different testing lab.

5G-coronavirus conspiracy theory spurs rash of telecom tower arson fires

I mean, Jesus, Lefties have brain damage.

It may not be lefties.

Priests reveal how coronavirus crisis has unleashed ‘intense demonic activity’

they would know

No matter how many times I read some article like that, I'm always flabbergasted at how differently some people's minds work. I couldn't even read it all - I simply lack the endurance to wade through that much delusion. A mind like that is entirely alien to me. I find it far more disturbing than ENB's cherry-picking.

There's actually very little evidence that Jesus has, or had, brain damage.

What about Paul?

Well, Paul is a lefty.

Paul is dead.

Yeah, I suppose that's about as brain-damaged as you can get.

"That was, um, a hoax, right?"

Pink Floyd had Brain Damage, but Gilmour is a righty. No matter which hand Waters prefers, he is definitely a lefty.

Eh. Lame.

FTR, Gilmour is just as left-wing as his erstwhile bass player. He just doesn't screech about it every time he opens his mouth. Unlike Waters.

More bad economic news.

Charles Koch current net worth: $48.7 billion

We. Need. To. Open. Our. Borders. Now!

#HowLongMustCharlesKochSuffer?

#Meh

...there are very few meaningful differences between the Republicans and Democrats.

Well I certainly hope that Gillespie didn't get the coronavirus just to figure that out! Also, I hope he doesn't get the coronavirus.

"This is the moment to not be going to the grocery store, not going to the pharmacy, but doing everything you can to keep your family and your friends safe."

No.

This is the moment to accept that 'saving just one life' is not the reason to demolish the economy and nose-dive into poverty.

Stuff that PANIC!! flag up your ass, lady, stick first.

This is what happens when you get liberals teaching science for the last 4 decades on public schools, a belief that humans are fragile. This is peanut allergy bullshit cranked up to 11.

Cops break up Brooklyn funeral for coronavirus victim as mourners ignore social distancing

Police were forced to break up a Brooklyn funeral on Sunday after dozens of mourners gathered in violation of the state’s social distancing rules.

See, the media are liars who are propagating this hysteria as if any of these state rules on keeping distance from one another are constitutional at all.

Tell the government to fuck off.

The media rooting so hard for hydroxychloroquine to not work gives me a sad

Chernobyl radiation levels skyrocket as forest fires surround power plant

For anyone who hasn't watched the show "Chernobyl", watch it. It's terrifying.

Replace the nuclear reactor with a respiratory virus, and you're getting a look at China's response.

This mess.

It's looking like more and more the 'self-isolation' and quarantines should have been targeted to the most vulnerable demographic. For the rest, it should have been go about your business. Keep your social distance, wear gloves, and a mask preferably. Be responsible.

Instead, an irrational 'one-size fits all' blanket is forced where some people will pay a heavier price than others.

In my circle of friends, one guy is gung-ho we must do it to save a life!

But he's not going to be affected on any level. He'll continue to get his six figure salary.

Me? Because the government shut my business down, I have to go on EI. Ask me how I feel about this. Ga'head. The paper work alone makes me want to vomit.

Same friend, when I mentioned about our buddy's business also being shut down and isn't sure he'll have a business to return to because the suppliers may all be gone, said, 'they have money. I'm not worried for them.'

He softened his take but that was his initial feeling which disappointed me greatly.

Except, if he'd think it clearer and deeper he'd realize the company employed 35 workers with minimum salaries of 50k CDN.

Notice how during the GM bail out, that was justified because if the suppliers failed the economy collapses. Here, we probably have a case where thousands of suppliers could go under if SME's are shut down.

But in this case, crickets.

Sure Canada is responding by giving us loans but these are still LOANS. Not bail outs. So at best, we go back to our businesses and pick up the pieces for Lord knows how long this will take with the added albatross of debt we didn't want.

Mob Panic 1.

Healthy skeptical minds 0.

But keep pointing fingers at Trump or other wrong places.

Assholes.

the added albatross of debt

During times of crisis added debt doesn't count. You know, like added calories during vacation.

Doesn't count for assholes like Bill Gates and other unaffected.

Speaking of which, we also need to reign in the doctors. Of course they're gonna force the precautionary principle. They have one mandate: Save as many lives as possible. We should take their advice and make a decision. I fear we're letting them dictate policy.

They'll still have a job after the dust settles.

And then will come in the unfalsifiable assertions 'we had to do it! We saved your lives!' narratives.

http://www.zerohedge.com/health/peter-navarro-explodes-faucci-heated-showdown-over-hydroxychloroquine

The doctor/nurse/etc. worship was insufferable, even before this turned it up to 11. These people are acting like it's a tragedy they have to watch patients die. I mean, if seeing old, sick, weak people die really bothers you that much, I think you might have made the wrong career choice. And if you think not being able to save every sick person is a failure on your part, you are an idiot.

If a doctor or a "climate scientist" says it (as long as they're not a heretic like Dr. Drew or any scientist who questions climate change orthodoxy), it is gospel and any recommendations must be implemented immediately and without consideration of repercussions.

It's not quite as obnoxious as the "thank you for your service" silliness during the 2000s, but it's getting there.

I hope it doesnt get to thin blue line levels of worship

"Instead, an irrational ‘one-size fits all’ blanket is forced where some people will pay a heavier price than others."

Actually, when many will pay, in money, life quality, and even health, for the benefit of a few. And the benefit of the media. And maybe some politicians.

"'It’s looking like more and more the ‘self-isolation’ and quarantines should have been targeted to the most vulnerable demographic. For the rest, it should have been go about your business. Keep your social distance, wear gloves, and a mask preferably. Be responsible."'

As a member of one of the "vulnerable" populations, I have been saying this since the get-go. Since a huge percentage of the older, more vulnerable, population (65+) are retired or semi-retired, "self-isolation" is of little consequence. And for those in this group for whom it is a major deal, it certainly wouldn't cost $2.5 trillion to bolster their income for a few months. In fact, in most instances, family and friends would be enough support. For me, self-quarantining is little more than an inconvenience.

Exactly. I’ve been saying this for the last month.

+

It's what we've done regarding pneumonia since, like, forever. Covid-19 is one cause of viral pneumonia. There's never been a push anything like this to stop the spread of pneumonia viruses in the general public, except for the particular type of agent (that can cause pneumonia), influenza. Mostly we don't even try to track the viruses that can cause pneumonia.

Pneumonia kills 50,000 Americans in an average year. Of course they're almost all debilitated to begin with, and frequently institutionalized.

When the vital statistics for 2020 come out, if they count Covid-19 deaths separately, watch and see if there isn't a corresponding dip in pneumonia deaths other than from Covid-19. It's killing those who would've died from some other pneumonia.

One thing seems for sure, the "lock-down" will also reduce the deaths from the "regular flu." I suspect the overall death from flu will be on the high side (there were 90,000) deaths just a couple of years ago, but not as bad as some are predicting.

We don't have to wait that long!

https://imgur.com/N9Z4LcF

Exactly. Here, all the local "retirement communities" (SNFs, assisted-living facilities, etc.), locked their doors even ahead of the governor's order, and we still don't have a single reported case in the County.

A tiger at the Bronx Zoo has COVID-19.

Good to know where we stand relative to tigers in terms of getting tested for the Boomer Doomer flu

Be they find a ventilator for it.

Bet it's all the fault of that bitch Carole Baskin.

Johns Hopkins ABX Guide Coronavirus COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2

Updated March 30, 2020 ABX Guide for COVID19.

The mortality rate is less than that commonly ascribed to severe community-acquired pneumonia (12–15%)....

Early Wuhan experience suggested a case fatality rate as high as 4.3%, but likely 2% elsewhere in China.

Preliminary evidence suggests two strains of SARS-2-CoV circulating: one associated with milder illness (~30%), the other with severe illness (70%). Additional sequencing studies may help define if further mutations may lessen virulence and also help trace spread.

Case fatality rates in other countries (as of March 2020) appear lower, but are higher in elderly, sick populations (e.g., Evergreen Health, Seattle, WA; Northern Italy).

Preliminary evidence in humans and SARS-CoV-2 infected rhesus macaques suggest that reinfection does not occur.

Most but not all patients recovered from COVID-19 producing neutralizing antibodies that are likely sufficiently protective against infection.

Coronaviruses immunity may not be long-lasting (e.g., 1 to 3 years) based on work with routine coronaviruses, SARS and MERS.

They forgot to add:

-Started in China followed by a massive cover up of lies enabled by the WHO.

-Intense propaganda campaign begun to summon useful idiots to the cause.

- American media focuses on blaming Trump. Wishes if it contacts Wuhan, they be treated in China because of the best care provided.

"Corona suspending production

That's one way to stop all the Corona parties.

When do we get our ration cards our our quota of fun?

If you're dumb enough to listen to anything Trump says then you probably deserve what you get.

"If you’re dumb enough to listen to anything Trump says then you probably deserve what you get."

If your TDS is this advanced, we can only hope for a very slow, very painful death.

Why waste a ventilator?

Anyone else getting inundated with commercials calling this covid reaction the new normal? They are now trying to engrained this panic into us

I was told, over the weekend, that the government is recommending now that people wear masks outside since the virus is transmitted through the air more easily than was originally understood. That's why this person doesn't want to read in the gorgeous flower garden in her backyard anymore--because she doesn't want to wear a mask and she's afraid of the airborne virus.

Huh?!

Turns out, she was talking about something she saw on television, where the federal government was suggesting that people wear masks "in public places". When you go to the grocery store, when you go to the pharmacy, when you're in a public place with a lot of other people, in an enclosed building, they suggest you wear a mask. But guess what? The primary purpose of those masks isn't to prevent you from breathing in other people's air. The primary purpose of those masks to prevent you from infecting other people!

Regardless, the fear that by sitting in the beautifully landscaped flower garden in your backyard, that you need to wear a mask because someone down the street has the coronavirus and by exhaling in their homes or yards or driving down the street, they're putting you at risk of infection is . . . not what the government is saying. That announcement was mostly directed at people in New York City. It's just that other people have a tendency to assume that what's being said is being said to them, especially when they're scared.

If you're an older person with a cancer history and a heart condition and they're giving advice to New Yorkers about what to do when they all go to the same grocery store, it can feel like they're talking to you--even though you're in suburban southern California, you've had all your food delivered for weeks and haven't left the house, and you have acres of land between you and your neighbors . . .

Just a little tweak of context, and suddenly everything President Trump or anyone else in the government else says is life or death for you and everyone you love, and I'm seeing so many journalists exploit that shit. It's making me sick. When this is over, I will endeavor to defend the First Amendment rights of journalists everywhere, just like I defended the human rights of terrorists, but, wow, the news media is really putting itself in the same boat with some nasty fucking people.

Truth #1: people are idiots.

Now construct a civilization, society, and institutes from there. Or maybe we already did.

They're not stupid. They're just scared.

And the news media exploiting their fear to sell them incoherent bullshit doesn't help one bit.

And this is the way a lot of people become educated on a topic.

Before 9/11, the average American knew about as much about Islam as they do about Sikhs or the Druze today. A year from now, average Americans will know more about infectious disease than well-educated people did a year ago.

In the wake of 9/11, an awful lot of people believed Saddam Hussein was involved because of the anthrax attack--and because they didn't understand Al Qaeda's goals or why Al Qaeda would never have collaborated with Saddam Hussein. As people became more knowledgeable, they became less susceptible to bullshit.

A year from now, seniors probably won't fear sitting in their giant backyards without a mask--even if there is another coronavirus. They'll get the truth sooner or later--in spite of the incompetence of the news media.

The stupid and scared are making the rules. The rest of us are trying to placate them but it's not working.

Time for some tough love. Tell these lunatics to sit down and STFU.

Your absolutely right here.

I often wonder why journalists nowadays are so hive-minded and well... such terrible people by-and-large.

I'm also baffled by all the normalization of lying.

And it's not just differences of perception or little-white-lies, but enormous, easily detectable, outright falsifications. And once they are caught they immediately drop the lie like it never happened and start a new lie.

Particularly in political journalism today... constantly, over the entire political spectrum, in virtually every article and column.

"Fauci pushed back against [economic adviser Peter] Navarro, saying that there was only anecdotal evidence"

Even if this exchange actually happened, it doesn't mean much. Another two European national health agencies have approved hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19 and Italy has just authorized the wide distribution of hydroxychloroquine on medical prescription from the very start of the infection.

In a normal time a nation could wait for the traditional double-blind tests that Fauci wants to see, but these aren't normal times. He’s a good man who's done his job for decades, but he’s never faced a crisis like this, and at 79 he’s not super mentally flexible. Anecdotal evidence is still evidence, and when it's overwhelmingly observed as in this case, it's time to pay attention.

Which brings me to the tone ENB uses above;

"President Donald Trump has been hoping so hard for hydroxychloroquine to work against COVID-19. But Trump advisor and infectious disease expert Anthony Fauci isn't so sure."

Does anyone else get the feeling ENB is actually 'hoping so hard' for hydroxychloroquine to fail, because Orange Man Bad? It certainly seems that way to me.

Well, I think it's fair to say that if President Trump weren't in office, there wouldn't be any uncertainty or difference of opinion, not even if there isn't any scientific consensus hasn't been established yet because we just don't have the data.

And that's because if President Trump weren't in office, the news media would take the word of the Democrat in office, more or less without question--instead of taking things Trump says literally, like someone who suffers from Asperger's syndrome, to make him look ridiculous.

The news media would certainly defend everything President Hillary said--as if not doing so made you a conspiracy theorist or a misogynist.

That's what they do. That's who they are.

I don't like Fauci, and his public... skepticism... of hydrochloroquine both goes against statements he made years ago and is a bit suspicious.

ENB definitely hopes it doesn't work.

Progress uber alles

The answer is Yes = Does anyone else get the feeling ENB is actually ‘hoping so hard’ for hydroxychloroquine to fail, because Orange Man Bad? It certainly seems that way to me.

Brown perfectly encapsulates the Left. She would rather see the deaths of Americans to bash POTUS Trump than to see the medication work. The revolting birdbrain Brown is not alone in her thinking. There are many sick people who think this way.

One thing driving this may be a desire not to drop the ball again on COVID-19 prep, as the administration has already done with tests, masks, and ventilators.

Not a fan of the president here (evergreen statement) and the administration made huge mistakes for those inclined to believe the federal government has more power than it legally and logically does, but Jesus Christ. This is a libertarian magazine. Nuance this a little more.

"...Nuance this a little more."

Orange man bad.

How do you add nuance to that?

The people who make tests, masks and ventilators are just like journalists and have been too distracted by Trump's tweets to do any real work since 2015. He should've done the world a favor and impeached himself the day after his inauguration.

It's been pretty disappointing to see ENB pushing this government-must-do-something mentality.

You should probably check your expectations

Orange Mag Bad

Yeah. Anyone who doesn't know how unreason staff will act like this have not been here for long or are in denial.

People are understandably frightened. Most national news is coming from cities and it's telling us to freak right out because that's what they're seeing outside their windows. And it may very well come in earnest for the suburbs and rural America. But city dwellers more than most are going to look to government for answers.

There may very well be no libertarians in a pandemic among urbanites.

It's hysteria. The media started the hysteria and they see the effects of Lefty Sheeple around them.

Most people in rural areas are not freaking out because we have been skeptical of MSM lies for decades.

Even john caught it... then he disappeared.

I know multiple trumpies who sound just like cnn. Its disheartening.

Considering the models they've been using are WAAAAAAY off in their predictions on the amount of healthcare resources required, even with these shelter-in-place and social distancing orders assumed in the model, it's eventually going to hit people that all this panic-mongering and economic destruction is fruitless.

Huge revisions to the model yesterday cutting resource use by up to 75% in some places. And since that model assumed full social distancing, reality should be EVEN WORSE!

Yep, I saw that. Here's IHME's Colorado numbers for April 5th that were displayed yesterday morning:

Projected beds needed: 4,507

ICU beds needed: 863

Invasive ventilators needed: 690

Here's the numbers after their 11:50 pm update last night:

Projected beds needed: 739

ICU beds needed: 137

Invasive ventilators needed: 116

I'm pissed now that I didn't get a screenshot of the chart from yesterday; should have assumed someone was going to catch that and change up the numbers. They're in full-on "cover our ass" mode now so they can justify all the panic-mongering and post hoc-"these worked out better than we thought!" rationalizations.

Note that you can't access their previous estimates anywhere on their site for comparison, although The Hill reported on April 2nd that they predicted peak resource use and peak deaths in Colorado for mid-April.

Somewhere, somebody has those things saved and will be doing a very public comparison.

I have been doing just that for the States that our business operates in: and it parallels what RRWP is saying for the 3 west coast states.

RNC Chairwoman Ronna McDaniel: Democrats' coronavirus voting plan – this is the way to undermine democracy

After failing with their first left-wing laundry list disguised as coronavirus relief, Democratic leaders are already plotting their next attempt to use the pandemic for political gain.

To be fair the DNC plots to use absolutely everything for political gain. It doesn't matter if it's cattle ranching, drinking straws, colorful area rugs, elemental copper, string theory or fake house plants.

The spirit of William M. Tweed deeply imbues his party.

+100000

LA doctor seeing success with hydroxychloroquine to treat COVID-19

It's almost like Trump is correct about a lot of things. Maybe the media should tell Americans about this fact.

I was assured by the medical experts on twitter that hydroxychloroquine is actually snake oil that should only be used by Lupus and arthritis patients. So I guess the good news is that snake oil isn't ALL bad.

He said he has found it only works if combined with zinc.

We've been throwing money at this thing all wrong. It should have been pennies, not (trillions of) dollars.

The press six months from now: "Demand for zinc to treat COVID-19 has led to an increase in mining activity for the mineral, which threatens to destroy precious wildlife habitat and increase pollution."

OK, folks, now is the time to keep Patrick Henry's stirring call to action in mind:

"GIVE ME LIBERTY (unless it means I might catch the flu)!"

The initial French test of hydroxychloroquine had half of the patients given a placebo, that half had longer recovery times and I believe one died.

Oh great. Now there's going to be a shortage of placebos.

Ug. Maybe we can make some fakes with sugar water or something?

That will require 18 months of testing with the FDA.

Well, I guess if it saves just one life.........

Field dispatch from state-controlled Soviet America, week 4:

Uneasiness is spreading throughout the land, as more and more people are starting to wonder if they'll ever go back to work again. The coordinated mass hysteria being spread by the state-controlled dependent media doesn't help. Some friends are reporting having difficulties sleeping. Meanwhile, critical supplies of certain items are still low. Don't know how we're going to make it to June like this.

In the hopes an adult monitors this newsletter, I'll let you know that after 30+ years of being a supporter and contributor, you guys can promptly F-off. You contribute NOTHING to the conversation and have become just another useless gnat buzzing around the left wing echo chamber. I'll take me time, attention, and money, and go somewhere else.

I hear you dude, but the sad truth is they don't care. The only people who really matter around here are the very tiny handful of billionaires who keep them afloat.

Yup 🙁

Word

"This is the moment to not be going to the grocery store, not going to the pharmacy, but doing everything you can to keep your family and your friends safe."

Which prompted another run on grocery stores. This is looking more and more like a political experiment.

It's really bad when even administration spokesmen are spreading fear and misinformation, and scaring the average person in thinking that anyone who gets this will be at serious risk of dying within a couple of weeks.

Trump knows perfectly well that it's complete, 100% total horseshit, but even he has been intimidated into no longer telling the truth about this now.

As long as we can agree that Orange Man Is Still Bad.

But Trump advisor and infectious disease expert Anthony Fauci isn't so sure about the anti-malarial drug as a cure for the new coronavirus.

This balloonhead also said the economy shouldn't be reopened again until we got down to "essentially no new cases, no deaths." He should have blown up his credibility right then and there, but people keep taking his dumb ass seriously. Now he's stating that if it doesn't get "globally under control," it's going to be a recurring problem. Someone needs to inform this moron that the Spanish flu strain is STILL active, 100 years later. He then said that we need to expect a resurgence next year. No shit--that's what happened during the Spanish flu, because the "social distancing," quarantines, isolations, and prohibitions against mass gatherings at the time utterly failed to prevent the spread of the virus, and the final resurgence in 1919 ended up being the worst of the spikes.

This guy is dangerous. He's actively working for the utter destruction of the economy in the name of a zero-risk policy, and the tell here is that he's trying to warn people off about a medication that's shown to have helped people recover, even though Cuomo and Whitner finally gave in and allowed off-label use for it, the FDA has provided a waiver for it, and European nations. He's claiming that we need to get cases and deaths down to zero before we can tell everyone to go back to work. That's not how viruses work. They stick around until people either get some kind of herd immunity, and/or a vaccine is developed.

Someone needs to get this clown off the stage, because in about a month or two, local/county/state governments are going to see their budgets implode from the lack of tax revenue, and then things are really going to get salty. Think 6.5 million unemployment applications is bad? Now imagine trying to process even more of those claims with about half the staff in place, because the rest have been put on furlough or are working for free.

I'm becoming concerned that Trump might be losing his balls, because this asshole should be fired yesterday.

He knows damn well that 100% permanently eradicating a virus is impossible, which makes him a lying, fearmongering piece of shit.

I think Fauci is doing his job. It’s Trump’s job to balance Fauci’s medical concerns against legal and economic concerns, and so far he has done that. I also think it’s good that this is happening out in the open.

The fact that progressives and leftists prefer a presidential pretense of competence and certainty from otherwise incompetent and insecure presidents like Obama is their problem.

Not to worry, POTUS Trump is properly focused on opening things up as soon as possible, when it is safe. Doctor Fauci is just an advisor, nothing more.

I'm REALLY curious as to what caused the sudden change in tone from him a few days ago, when he went from optimistic to full-on doomer.

Yeah, it's like Fauci started slipping something in his diet Coke to make him depressed and compliant. One hypothesis of mine, and I hope I'm right, is that he became convinced that we were approaching the worst of it so he switched to pessimist mode in order to make it look that much better when we turned the corner. Basically setting the stage for a "this was a dark time for our nation, but we pulled through together, now it's time to get back to business" post-apocalypse narrative in a couple weeks.

Imagine trying to pay all of those extant pensions.

Totally agree. It's going to be fiscal Armageddon already, without waiting another six weeks like these people want us to do.

FDR and Churchill projected optimism in very trying times. "Nothing to fear but fear itself", Victory etc. Some people won't be happy until Trump runs around yelling "the sky is falling, the sky is falling."

Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards attributed the high death rate to the state having "more than our fair share of people who have the comorbidities that make them especially vulnerable."

"All the diabetic fatasses around here are raising the mortality rates."

Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards attributed the high death rate to the state having "more than our fair share of people who have the comorbidities that make them especially vulnerable."

Is one of the comorbidities a susceptibility to sickle cell anemia? Albany, Georgia is a hotspot for the coronavirus largely due to an unusual number of people getting infected at a funeral - guess what race? AOC has claimed POC are more at-risk than white people, is this true? Is it racist to even suggest we might look into that? Because I've heard a story going around about some researcher suggesting the problem with the coronavirus is that it screws up the way red blood cells deliver oxygen to the body and creates a massive problem for the liver which explains why an anti-malaria drug seems to work on a virus. And why so many people on ventilators are dying, because assisted breathing is not the best way to deal with somebody with fucked-up red blood cells when what they need is oxygen and a blood transfusion to give their own immune system time to deal with the coronavirus. And why diabetes is also a strong comorbidity - problems with your lungs are bad enough, problems with your liver are just as bad.

But this is purely anecdotal and I'm sure the good Dr. Fauci is right to be skeptical that an anti-bacterial drug could possibly do any good against a viral infection. Give him and his buddies about 15 or 20 years to study this thing properly and I'm sure they'll come up with something to fix the problem. In the meantime, just keep yourself locked in your room until they tell you it's safe to come out.

Possibly sickle-cell related, but I doubt it. The greatest common denominator, if you go off of NYC's numbers, are obesity-related issues like heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, liver disorders, etc.

The family in New Jersey that attended a wedding and a bunch of them got sick--the same one used by the media to screech, "SEE IT'S NOT JUST THE ELDERLY LOOK HOW CONTAGIOUS THIS IS"-- was full of fatties.

Whatever the reason, it sure seems like there has to be some demographic aspects at play. Whether that is biological or just lifestyle/social norms related. In NYC, Manhattan has the lowest infection rate by far- almost half the infections per million that Queens and the Bronx have. Brooklyn is second lowest, followed by Staten Island. There seems to be a pretty strong correlation between degree of gentrification and infection rates there. In my state, WI, Milwaukee county has 1206 infections per million. The next most populous county, Dane county (i.e. Madison) is 501 per million. Now Madison is a less "urban" city than Milwaukee, so part of it could be a function of simple density. But, the demographics and types of living conditions are very different between the two areas as well. Consider some of the other hotspots- Detroit, New Orleans, Atlanta. And then there are counterexamples of populous regions that are not particularly hard hit, such as Hennepin County, MN (224 per million). This is admittedly subjective, but I don't think of Minneapolis as being "urban" in the way I do some areas of Milwaukee, Detroit, New Orleans, or Queens.

We have studied enough viral infections to know that it often not the virus that kills you, but an opportunistic infection. Antibiotics are not effective against HIV, but they are effective against toxoplasmosis. Given the distribution of COVID-19 deaths, cofactors are almost certain, and a bacterial infection is a likely cofactor. If the good Dr. Fauci doesn’t understand that much, perhaps he’s in the wrong line of work.

"AOC has claimed POC are more at-risk than white people, is this true?"

I have no doubt that AOC probably believes that the causes for that higher risk are "billionaires", "being unbanked", "capitalism", or any number of other things she doesn't actually understand.

So far, it's all but certain that COVID-19 runs roughshod over anyone who is already ill. Black folk in the US have much higher rates of diabetes, HIV, obesity, and hypertension than whites (not sure about "non-white Hispanics", or whatever the label du jour is for that group). COVID-19 is exceptionally dangerous for anyone with hypertension.

So, AOC is very likely right about this one, but for mostly the wrong reasons, as usual.

Averaging the gestimates of coronavirus fatalities in the U.S., you have about a 1 in 2,000 chance of dying from it (probably less if you're in good health). Only around 329,300,000 Americans should survive.

“The president now regularly describes the supply of ventilators and masks in terms of negotiations he allegedly made well and states didn't, making this into a competition where there should be cooperation to save lives.” Oh, so the opposition and the press (but I repeat myself) are allowed to slag off on him but he’s not allowed to rebut their claims? Is Reason staffed with a bunch of altruists now? He can take effective action but it doesn’t count if anyone knows about it? Fuck you assholes.

“Try hydroxychloroquine” means “try it with a prescription from your doctor under controlled conditions”. In fact, that’s the only way you can get the drug legally in the first place.

And if you have been asleep for the last few years, ENB, let me point out that drug stores actually have no-contact delivery right to your very home. I know, what will they think of next, right?

★i making extra PACHUP 19k $ or more US DOLLARS. Stay at home safe avoid from suffering from corona virus and work on line. Join now this job and start making extra cash online by follow instruction on the website......Check All Details…...

COPY HIS WEB...... Www.hit2day.ⅭOⅯ

"Anecdotes" piling up from coast to coast are showing nearly 100% effectiveness treating COVID-19 severely ill patients with the malaria drug hydroxycloroquine, azithromycin (Z-pak), and zinc.

https://www.facebook.com/drericnepute/videos/seriously-how-much-longer-are-we-goin-to-put-up-with-all-the-bs/212203320055065/