On the Money: Presidential Portraiture and Power in D.C.

Kehinde Wiley's pre-presidential works criticized inequalities and hierarchies of power. His presidential portrait doesn't do the same.

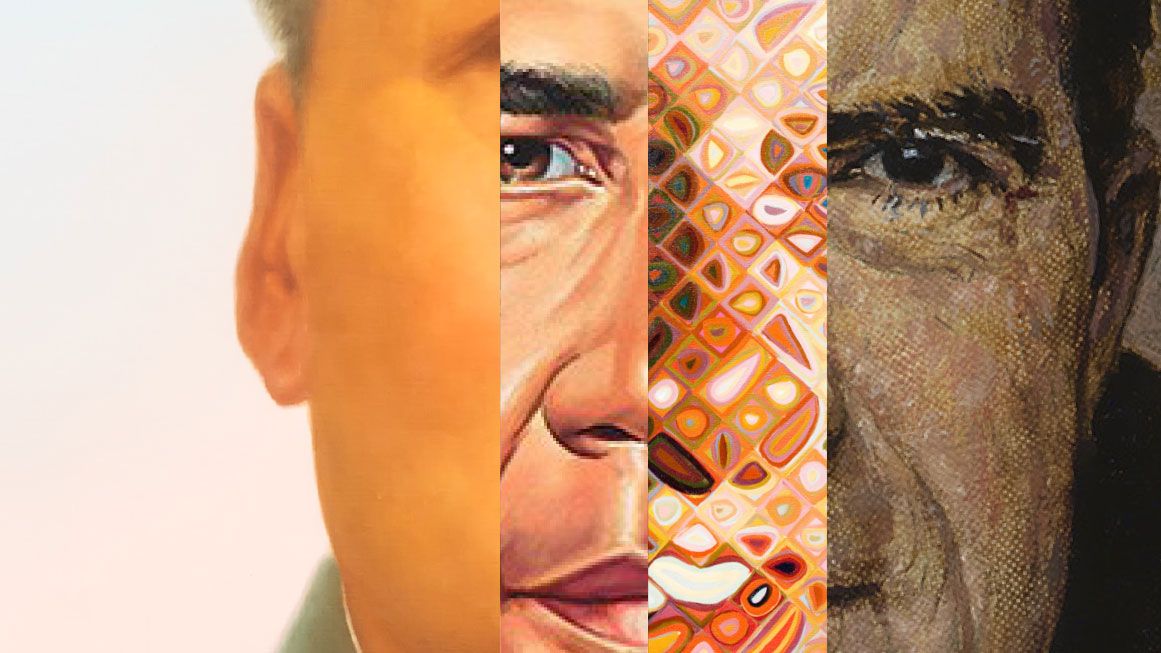

Kehinde Wiley's portrait of Barack Obama is in various respects quite different from the procession of presidential countenances in the National Portrait Gallery that you must traverse to get to it.

For one thing, it's more popular with museum-goers. For another, it's the only one that's a picture of, and the only one that's a picture by, a black person. And it feels very much of its moment—post-postmodern, we might say. Wiley's complex repertoire of techniques and meanings—figurative, collage-like, unrelentingly concerned with identity politics, stylistically eclectic but also coherent—is a pretty good summary of where art is now.

Despite the nowness, however, the Obama portrait also serves the same function as Gilbert Stuart's full-length George Washington: rendering a person into a symbol of state power.

Wiley's pre-presidential works criticized inequalities and hierarchies of power as well as the way such hierarchies are frozen into the history of art. His 2005 painting Napoleon Leading the Army Over the Alps is a pointed critique of Jacques-Louis David's heroic, neoclassical take on the same subject matter. The French emperor is replaced in the familiar equestrian composition with a black man.

Upstairs at the Portrait Gallery, near Amy Sherald's image of Michelle Obama, is a huge Wiley painting of LL Cool J enthroned, almost photoshopped over a rococo wallpaper in red and gold. It has a dynamic and amusing quality; Wiley is an extremely intense and conscious colorist. His Obama is, in comparison, frozen in his dignity, given a muted, hieratic treatment that suggests a medieval Madonna—though the 44th president is sporting a nice watch and features that pop into three dimensions, much like Cool J's, under the auspices of Wiley's dramatic, hyperreal modeling.

It's one thing to depict rappers and athletes with the triumphal dignity normally reserved for presidents, or to replace oppressive (and white) political or military leaders in heroic portraits with black figures. The project of depicting the most powerful person in the world in the same way risks conveying the opposite message. Wiley's Obama is a contradictory image in the America and the art world of this era. The portrait is an image of a hero of an oppressed race, like a portrait of Malcolm X or Martin Luther King Jr. In fact, Obama is often associated with King: As the 2008 T-shirt had it, "Martin marched so Barack could run." Yet President Obama was Martin Luther King with a world-annihilating nuclear arsenal and a sprawling system of internment facilities. It is hard, in this context, not to think of Wiley's Obama as conveying something of the same message as the other paintings of presidents in the Portrait Gallery. As with James Reid Lambdin's Zachary Taylor, for example, its subject is rendered as a hero: idealized, made classical. Both men appear implacable.

The Obama portrait, even if it is painted in the same style as Wiley's previous works (or perhaps especially because it is), serves power in the most traditional way that art can—in just the way David's portrait served Napoleon, portraying the emperor as he wished to be seen by the Europe he was in the process of conquering. The Wiley Obama participates in the tradition of street art celebrating cultural heroes and resistance leaders. At the same time, it participates in the tradition of the late Wang Guodong's official portrait of Mao, which still looms over Tiananmen Square and appears in thousands of iterations all over the country. It takes political power and turns it mythological.

I would like to believe that Wiley thought hard about such matters before he accepted the commission and as he executed it. But if he did, I can't read the results from the painting itself. Ultimately, it has settled comfortably into the Hall of Presidents since its sensational (for a painting) debut in February 2018, back when you had to wait in line to see it.

In Times Square in late September, Wiley previewed a large equestrian statue on a stone plinth, intended eventually for Richmond as an answer to its parade of Confederate generals along Monument Avenue. "Today," Wiley said, "we say yes to something that looks like us." That's what people seem to be looking for in all media all the time: something that allows them to affirm themselves, understood as race/gender/sexuality congeries. In the Portrait Gallery, however, Barack also looks something like William Henry Harrison or Bill and Melinda Gates, who share the upstairs gallery space with LL and Michelle. Having perhaps less sheer power to convey, Sherald's portrait is primarily about the former first lady's dress, whose designer is credited on the card.

The audience on the days I visited in October was notably younger and blacker than the Portrait Gallery's once tended to be. Visitors moved their way through the procession of dead white guys at speed, occasionally pausing for a selfie with William McKinley or Teddy Roosevelt. They were headed to the Wiley, of course, and gathered before it, though not in the sort of numbers it was pulling a year ago.

As you traverse the presidents at the Portrait Gallery, you traverse the art styles of the last few hundred years in attenuated or desiccated form. Often, in the 19th century, presidential portraitists were hired from or had trained overseas, where they learned their craft painting European aristocrats. Eliphalet Frazer Andrews' Rutherford B. Hayes has a touch of the pre-Raphaelites; Anders Zorn's Grover Cleveland has a whiff of impressionism, a bit bewitching (believe it or not) in the fundamentally charmless context. By the 1960s, when the United States had emerged as a center of world art rather than a provincial backwater, we start getting a flavor of the domestic and the contemporary in Elaine de Kooning's abstract expressionist John Kennedy and Chuck Close's disquieting Bill Clinton, which appears to be training its beady stare on the Wiley Obama as the latter looks away and tries not to notice. I haven't gone in with a measuring tape, but I think the Close Clinton is the biggest work in the Hall of Presidents.

I imagine that I wasn't the only one wondering where Donald Trump's portrait will be installed. You make the hall of presidents merely by being president, and so far no one has been disgraced or #MeTooed out of it (though Chuck Close himself has been accused of sexual harassment). Trump's natural spot would be opposite Obama, in confrontation but also in collaboration—because all these figures converge in the gallery into a single narrative, meant to move you as a solemn procession of great men.

And it is men, about which even the Portrait Gallery has a bad conscience. On the way in to the presidents, you get a group portrait of four female Supreme Court Justices (O'Connor, Ginsburg, Sotomayor, and Kagan). They seem pleasant enough, though they have a bit of the quality of caricature. They dangle over the uncanny valley, as though they were achieved by projecting photographs onto the canvas and painting over them. Wiley's Obama has the same effect. "He looks so real," said one young woman to her companion as they took pictures before it. "Yeah. So, so real," was the response, which may have been sarcastic. Regardless, the painting holds court, with people spread out before it in adoration.

The best actual painting might be Norman Rockwell's Richard Nixon, who, amazingly, comes off as the friendliest and most easygoing presence in the whole space. Putting it mildly, that wasn't the effect that Wiley was aiming for with his Obama, and there is no hint of mercy in that stare. The card next to the Nixon explains that Rockwell didn't know how to approach the man, about whom he no doubt had very mixed feelings, and that he settled finally on straightforward flattery. Indeed, all these artists flattered their subjects, though perhaps none so transformationally as Rockwell.

The one rival in this regard is Stuart's monumental Washington, who is portrayed as a noble classical statue, a chunk of roseate marble rather than a human body. Appropriately enough, Jean-Antoine Houdon's ultra-familiar portrait bust sits whitely nearby. These images are so familiar that it's impossible to truly see them. They function as civic emblems rather than works of art. Nevertheless, Rockwell's Nixon and Stuart's Washington make you wonder just how misleading the rest of the images also are. Portraits are part of the way we understand, and falsify, our history.

My hometown of Washington, D.C., is rich in presidential portraiture, from the flat to the statuesque, in paint and developing fluid and bronze and marble, in poetry and architecture. The noble countenances of our paramount political leaders preside over, or perhaps infest, the city named for America's first president. The District of Columbia was in fact conceived as a sort of portrait: a late constructive project of the Founders, a sort of three-dimensional Constitution that one might stroll or ride through.

The people walking grimly back and forth on F Street outside the Portrait Gallery when I was there probably had some presidential portraits in their pockets or pocketbooks. These images have a direct cash value; they are legal tender, backed by the full faith and credit of the United States of America, for of course some of the works in the Portrait Gallery have ended up on our currency.

If the U.S. is printing money still in 50 years, Wiley's Obama might be on the $20 bill. The Fed isn't likely to cash the Close Clinton, however, both because of the style of the painting and the lifestyle of its subject. Many presidential portraits don't end up burning a hole in our pockets; it's hard not to be struck by the sequence of mediocrities between the peaks—the run from Van Buren to Buchanan, for example, and the post-Lincoln parade into the 20th century. Personally, I'm not overwhelmed by the litany from Truman to Trump, either.

Millard Fillmore does not appear particularly impressive. Neither does James Knox Polk, so the card next to his portrait does the work for him: "Driven and determined, Polk took office with a limited agenda, accomplished all of it, and left office, as he planned, after only one term." We shall not see his like.

As David portrayed Napoleon with various emblems of power, Stuart gives Washington a sword, a modest throne (but still a throne), an elaborate silver inkwell, and some books (titled Constitution of the United States and American Revolution). There are classical pillars and a glimpse of sky. The general-turned-president makes a sweeping gesture with his right arm, welcoming the birth of a nation, as it were. The French emperor, in comparison, is at once grander in his full military regalia and more modest-looking, with his hand tucked Napoleonically into his waistcoat rather than sweeping the world like a radar. The sword is there, though, and the throneish chair.

Jefferson poses for his painting with a slightly sexy classical sculpture, no doubt French, but as time goes on, American presidents look less and less like European conquerors. Whereas the early visual language of republicanism was grandly classical, later presidents get stripped down to look more like ordinary (if prosperous) American citizens, though ones whose faces must somehow be made to convey authority.

John Quincy Adams, by George Caleb Bingham, sets the chastened tone of the generation after the Founders, a beautifully flat and direct approach that contrasts favorably with the grand gestures that preceded it and with some of those that followed. The relatively modest, friendly style still finds its proponents, as in the portraits of Jimmy Carter and the Bushes. But something tells me that Trump's will be very grand, with just a touch of the absurd. Perhaps we can see previews in the works on display at Mar-a-Lago.

Washington B. Cooper's portrait of Andrew Johnson seeks to convey power by sheer sternness of countenance. Its grim features take on some of the iconographic weight that was once conveyed by swords and classical columns. By the time you get to the Obama, however, the thronesque chair has returned. This is perhaps because Wiley—like the producers of the 2018 Black Panther movie—wants to convey the idea of a black king, or perhaps because he wants to parody the whole idea of kings. He needs also, in an official portrait, to illustrate that the president of the United States is a citizen, not a monarch. But despite the relative modesty of Obama's suit, it's the kingliness that comes through.

This dilemma has faced all the portraitists in some form: Their charge is to render a presidential face at once human and Olympian, both an ordinary American (straight from the log cabin, maybe) and a worthy element in an exalted pantheon, preferably suitable for coinage.

The purpose of a portrait is somewhere between verisimilitude to the subject and public diplomacy for the government of the United States. You're casting an iconography into history: It'll be in textbooks. The basic function of all these pictures is to establish the legitimacy of the presidency by direct visual evidence, as school groups mill around. The portrait of the dear leader has always been a daunting, complex task, the kind of commission that would make any artist a bit nervous, and its various contradictory demands account for the odd remoteness of the atmosphere in the presidential gallery.

The Wiley Obama definitely does not interrupt this atmosphere. But Alexander Gardner's wonderfully intimate photograph of Abraham Lincoln from 1865 does. Gardner's treatment of Lincoln opts for the ordinary human being, relieving the oppressively deified and rather boring ambiance of the galleries. He looks like he's seen a lot.

The direct humanity of that picture is fully contradicted in D.C., though, on the other end of the National Mall. The colossal Lincoln enthroned at his memorial takes the place of Athena in an American Parthenon. Unveiled in 1922, Daniel Chester French's statue of Honest Abe is 19 feet high and sits on an 11-foot pedestal. Its hands rest on marble fasces, bundles of rods that were an emblem of authority for the Romans and that were possibly used in executions.

They were also used symbolically by Napoleon and Mussolini. Fasces provides the root of the term fascism. Wiley's Obama quite consciously plays with the elements of grand portraiture. It might even be construed as a critique thereof, given the rest of his oeuvre. It cannot exactly be a critique, however, if it is also an official presidential portrait, whose very reason for existing is to exalt the subject in our collective memory. This is an excruciating contradiction.

In an argument or speech, a contradiction must be refuted. Embodied in a painting, it could conceivably be enriching, setting off verbal disputes wherein the contradictions might be worked and worried, bit by bit. But like all presidential portraiture, this painting is not exactly a work of art. This is true even if every other work by Kehinde Wiley is art, and even if the Obama portrait could be art in another context.

Wiley's Obama is not intended, ultimately, to be open to interpretation. In Washington, D.C., the pictures and statues and monuments and money come pre-interpreted—"overdetermined," as theorists put it—saturated with official meanings, embedded in official histories, imprinted on schoolchildren. Wiley is going to receive that sort of silver-dollar immortality, but he's going to have to accept the accompanying demotion of his most famous work from the realm of art as well.

Show Comments (29)