The 2020s Will Be the Decade of Deficit Doomsday

America will have to pay for its spending spree and its wars.

The decade that just ended saw a period of uninterrupted economic growth. In the decade to come, we'll pay for squandering it.

Since the so-called Great Recession officially ended in the third quarter of 2009, the United States has enjoyed 42 consecutive quarters of solid if unspectacular economic growth. That's the longest run of uninterrupted growth since government economists began tracking the business cycle in the 1850s, far outpacing the average economic expansion of 18 months. Employment has increased by 12 percent, the jobless rate reached record lows, and America's gross domestic product (GDP) has increased by more than 25 percent.

It has been, by almost any measure, one of the best times in American history. Almost.

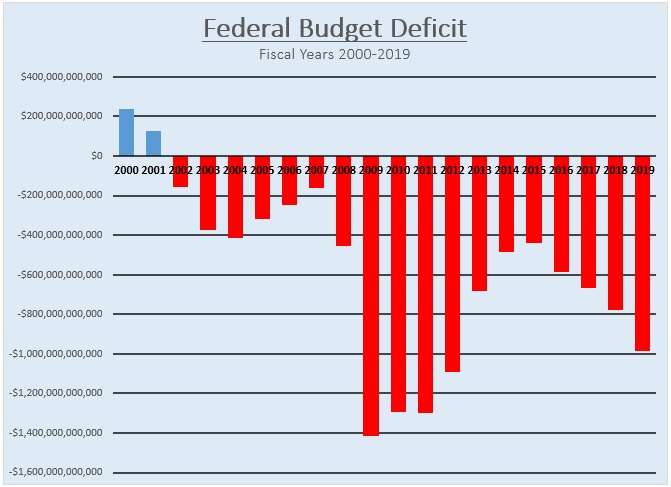

Hanging over this decade of good news is the gloom of a missed opportunity. After piling up trillions of dollars in deficit spending during the last recession, the federal government took some modest steps towards reducing that red ink during the middle years of the 2010s. But after Republicans took full control in 2017, spending skyrocketed and the deficit inflated again.

Since Trump was inaugurated, Washington has added $4.7 trillion to the national debt—almost entirely the result of a gigantic spending binge, but with a small assist from the 2017 tax cuts, which reduced revenues without offsetting spending cuts.

Now, more than a decade after the last recession ended, the United States is carrying a record amount of debt: more than $23 trillion. The country is on track to add more than $1 trillion to that total in every year of the coming decade, with old age entitlements ramping up as Baby Boomers retire and the country as a whole ages.

"Debt matters because it's the one issue that impacts all others," says Michael A. Peterson, CEO of the Peter G. Peterson Foundation, a nonpartisan policy center dedicated to fiscal issues. "Debt threatens our economic health and hinders our ability to make important investments in our future. If we want to tackle big issues like climate change, student debt or national security, then we shouldn't saddle ourselves with growing interest costs."

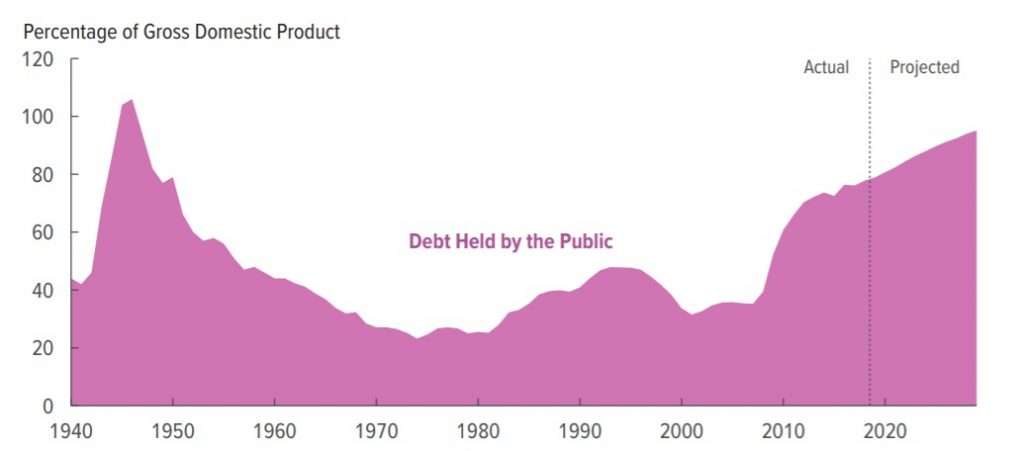

According to the Congressional Budget Office, the national debt will approach the size of the entire U.S. economy by the end of the current decade—and will keep on growing until it hits 144 percent of U.S. GDP in 2049. The current situation, warns the Government Accountability Office (GAO), is "unsustainable."

Compare all this with early 2001, at the end of the second-longest economic expansion in history. The federal government was running a surplus. The national debt was falling and amounted to only 31 percent of GDP. That's what you'd expect to see now, since deficits typically fall when the economy is growing and grow when the economy is rotten.

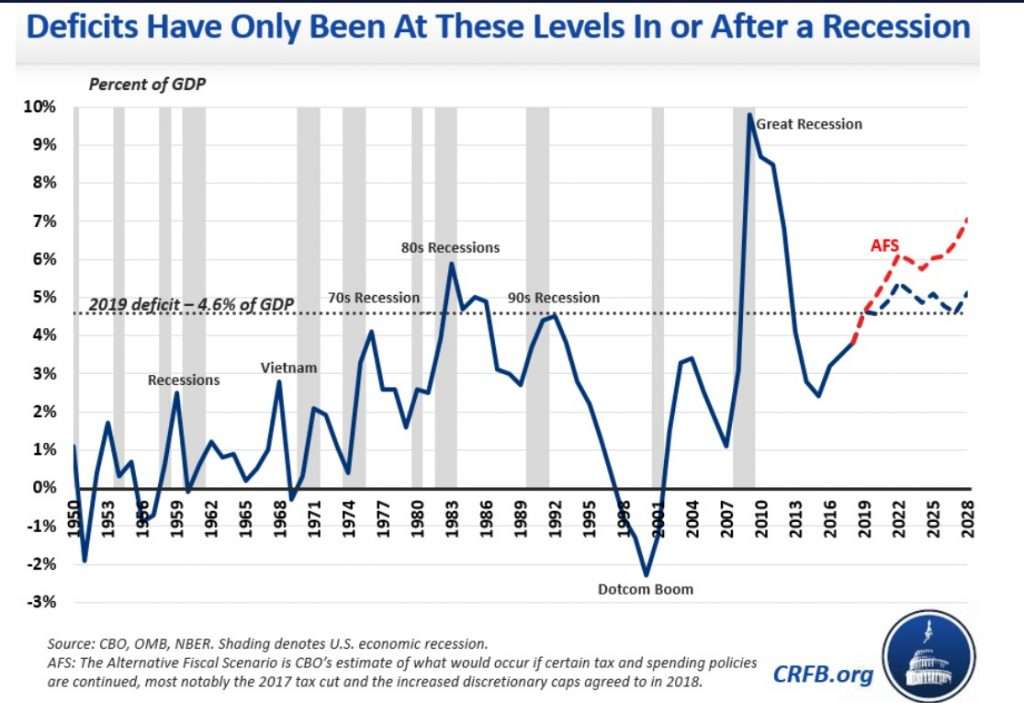

Indeed, since the end of World War II, the U.S. has seen deficits greater than 4 percent of GDP only in years when the country was either deep in the throes of a serious recession or emerging from one.

In the short term, deficit spending—or tax cuts that aren't offset with spending cuts—can juice the economy and boost growth. But in the long term, high levels of debt drag down economic growth. The CBO projects that the average American household will lose between $2,000 and $6,000 in annual wealth by 2040 if the current trajectory continues. It also says America's GDP will shrink by 2 percent over the next two decades if current policies continue and the debt keeps growing.

And the CBO projections are probably too rosy. They predate the approval of a new bipartisan budget deal in late 2019 that is expected to add another $1.7 trillion to the national debt over 10 years. Furthermore, the CBO is required to build projections based on current policies. Those assume, among other things, that some of the 2017 tax cuts will expire in the middle of this decade. Politically, that's unlikely to happen.

Worse yet, the CBO's projections don't account for the inevitable eventual end to this run of economic growth. If we're running a trillion-dollar deficit in the good years, what happens when the next downturn occurs?

"A recession could quickly push the deficit up towards $2 trillion," says Brian Riedl, a former Republican congressional staffer now based at the Manhattan Institute. A recession would likely trigger politically motivated calls for even more deficit spending, causing the debt to skyrocket even more than it already has.

It might also cause interest rates to spike, compounding America's debt problem. Every percentage point that interest rates rise will add $1.8 trillion in added costs over the decade.

"A nervous bond market could demand higher interest rates, further weakening both the economy and the deficit," says Riedl. "So while the economy looks strong and the deficit seems irrelevant, the fiscal situation is quite fragile."

It may require a crisis before anyone in Washington takes the situation seriously. The American political system seems incapable of planning for the long term. Even passing a federal budget through the normal committee process appears to be impossible, a testament to the failure of both parties' current congressional leaders. Congress lurches from one crisis to another—some real, some manufactured to score political points—and Trump's tempestuous presidency has only made things worse.

Assigning blame isn't the most important thing, but there is plenty to go around. The Trump administration and current crop of Republicans in Congress have made the problem worse than it already was. Some of them—like former deficit hawk Mick Mulvaney and former House Speaker Paul Ryan, who made his name in Congress as the GOP's budget-maker—deserve special ignominy for abandoning their fiscal conservatism when it was most needed. Trump came into office promising to eliminate the national debt in eight years, and that's even more of a joke now than it was then.

Meanwhile, Democrats' aversion to spending reductions and their refusal even to consider changes to entitlement programs—the biggest driver of the national debt—are equally large obstacles to any meaningful attempt at fixing this mess. The party's progressive wing is pushing for Medicare for All and expanding Social Security benefits, while elevating economic theories that say we should ignore the deficit.

And neither party seems to have a serious plan to rein in military spending, despite two decades and more than a trillion dollars spent in the Middle East quagmire.

In contrast to their elected officials, most Americans believe the debt and deficit are important. A Pew Research Center poll conducted earlier this month found that 53 percent of Americans view the federal budget deficit as a "very big" problem facing the country. That's a larger share of the public than the portion that views terrorism (39 percent), racism (43 percent), or climate change (48 percent) as a major problem.

But you'll hear much more talk about climate change, terrorism, and racism during the 2020 election. You'll here much more talk about many other things too. Neither party is taking the debt seriously right now, and no prominent national politicians appear positioned to lead a deficit reduction effort—at least not until the next Democrat is inaugurated and Republicans pretend to care about spending again.

"Lawmakers should work to manage our fiscal outlook now, when the economy is performing well and while we have time to manage the debt gradually and responsibly," says Peterson.

We had time. We may yet have more. But Washington is more likely to squander the 2020s, just like it did the latter half of the 2010s.

Show Comments (157)