Trump Says Tariffs Are Driving American Businesses Out of China. Actually, 87 Percent Plan To Stay.

Foreign investment in China has not declined since the start of the trade war, either. In fact, it continues to grow.

As it has become increasingly obvious that the costs of the trade war are falling on American consumers and businesses, President Donald Trump and his supporters have taken to arguing that even if Americans are being hurt, China is being hurt worse.

Usually, this takes the form of a claim that businesses are fleeing China to avoid the costs of the tariffs.

China wants to make a deal so badly. Thousands of companies are leaving because of the Tariffs, they must stem the flow. At the same time China may be hoping for a Democrat to win so they could continue the great ripoff of America, & the theft of hundreds of Billions of $'s!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 10, 2019

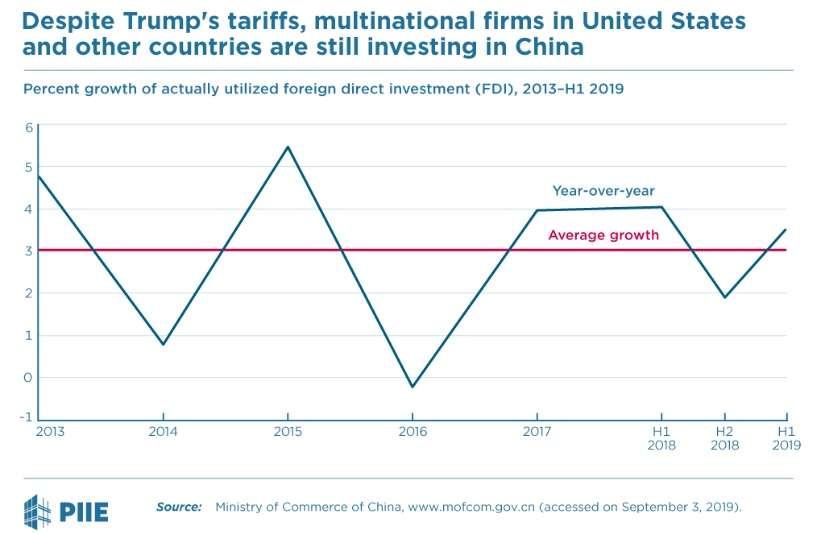

But like many other claims made by the Trump White House regarding the trade war, this one appears to be false—or at least way overstated. Foreign investment in China has not declined since the start of the trade war, according to Nicholas Lardy, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE), a trade-focused think tank. In fact, the growth of foreign investment in China has increased by about 3 percent on an annualized basis—about the same rate as in the years before the trade war started—since mid-2018 when Trump put the first round of tariffs on Chinese imports.

"Despite U.S. tariffs on China's exports to the United States, it appears, at least so far, that multinational firms, including those based in the United States, continue to find China an attractive environment for new investment," writes Lardy in a post published Tuesday on the PIIE blog. "Thus, Trump's claim that an exodus of foreign firms will force China to capitulate to US demands to settle the trade war is wishful thinking at best."

Lardy's findings track with what the U.S.-China Business Council, an industry group that represents companies doing business in both countries, reported in August. In a survey of its members, the group found that 87 percent had not moved out of China and did not have any plans to do so. That was down from 90 percent in a similar survey conducted a year earlier, but that slight decrease is a far cry from the Trump administration's claims that China is hemorrhaging businesses.

To the extent that businesses are trying to relocate supply chains outside of China, the main beneficiaries are countries like Vietnam and Mexico—not the United States. And such relocations were already ongoing before the trade war, according to A.T. Kearney, a manufacturing and trade consulting firm whose annual "Reshoring Index" measures domestic manufacturing of consumer goods against imports of the same products from 14 lower-cost countries in Asia. Vietnam's exports to the United States have doubled since 2013, for example, but the rate of growth skyrocketed during the first quarter of 2019.

Relocating out of China is a costly and complicated process—one that many businesses may be hesitant to undertake when there is so little certainty about trade policy. For American companies doing business in China, it probably makes more sense to just absorb (or pass along to consumers) the costs of the tariffs and hope things get better soon.

"If a manufacturer has to source different parts from different countries, that's not just as simple as picking up the phone and saying 'do you have this part and can you send me 500 of them,'" John Kirchner, executive director of congressional and public affairs for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, explained last month. "It's a long, expensive process for employers and businesses to change up their supply chains."

And it's a process that makes even less sense for American businesses that are actively engaged in making products for Chinese consumers. As Lardy has pointed out, "a large share of foreign firms in China, especially U.S. firms, are there primarily to produce goods to sell on China's still rapidly growing domestic market."

Once again, it turns out that international economics are more complicated—and more difficult to design—than the president seems to think.

Then again, Trump does appear to understand that on some level. After all, if the tariffs were having their desired impact, he wouldn't have to "hereby order" American companies to stop doing business with China.

Show Comments (67)