Democrats Are Retreating on Single Payer Health Care

It’s not just obstructionist Republicans who won't buy into Medicare for All—it’s Democrats themselves.

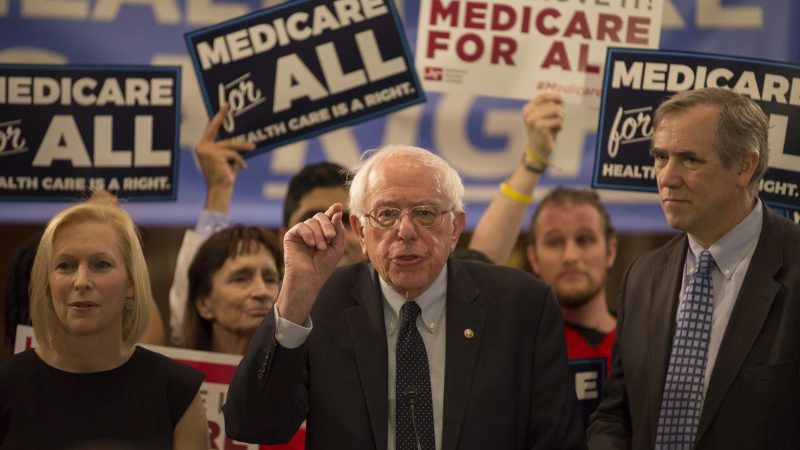

A decade ago, single payer health care—the government-run health care system that Sen. Bernie Sanders (I–Vt.) refers to as Medicare for All—was a fringe idea in the Democratic Party. President Obama positioned his health care law as an alternative to the notion of a fully government-run system, and the few Democrats in Congress who supported single payer tended to do so softly, believing that most Americans would reject the idea.

When former Sen. Max Baucus (D–Mont.) led negotiations over the legislation that would become the Affordable Care Act, he had one rule: All options would be up for discussion—except for single payer. As Baucus tells Robert Draper of The New York Times in a sharply reported feature on the rise of single payer as a force in Democratic politics, the senator was sympathetic to the idea, but didn't believe America was ready. Given how difficult it was to pass the comparatively less radical plan that became Obamacare, I'd say he was right.

Over the last decade, however, single payer has become a widely held policy preference on the left—what Draper describes as a "litmus test for progressives," with more than a hundred backers in the House, and multiple top-tier supporters in the race for the Democratic presidential nomination. Medicare for All, Draper writes, has gone mainstream.

Yet in recent weeks, there are also signs that the momentum has slowed, and that some Democrats are retreating—or at least proceeding with caution.

Most prominently, there is Sen. Kamala Harris (D–Calif.), one of the original co-sponsors of Sanders' Medicare for All bill in 2017. After months of backtracking and flip-flopping on whether she supports eliminating most private health insurance, as the Sanders plan calls for, she appears to have fully reversed course, expressing discomfort with the Sanders plan and releasing her own (confused) competing plan.

The party's old guard meanwhile, continues to think Medicare for All is a bad idea, with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D–Calif.) repeatedly questioning it, and former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D–Nev.) saying last week that it would be a problem for Democrats to back it in the 2020 election because it couldn't pass. Former Vice President Joe Biden, who represents this wing of the Democratic Party and is the primary field's most prominent critic of Medicare for All, remains at the top of the polls.

Sanders himself, meanwhile, recently modified his plan in response to concerns from unions, suggesting that even Sanders is not completely unmoved by criticism of his plan, at least if it comes from the left.

Meanwhile, it appears that there's little enthusiasm for single payer legislation where it matters—among the Senate Democrats positioned to exert the most influence over any future legislation.

Ezra Klein of Vox recently spoke to a quartet of upper chamber Democrats about their health policy plans. He found that they had ambitious expansions of Obamacare in mind, and no plans to seek Republican votes, assuming that their opponents would oppose any plan Democrats put forward. So these Democrats are feeling ambitious and expansive about health policy and unburdened by the need to compromise with Republicans. Yet even now they remain wary of the sort of full-fledged single payer system called for in Sanders' plan, largely because it would abolish most private coverage:

Which isn't to say Senate Democrats are prepared to abolish private health insurance. As in Wyden's comment, the word "choices" came up a lot in my conversations.

"As a practical matter, the way we move forward on health care has to be recognizing people's current insurance system and allowing people to make choices," says Stabenow. "If everyone chose the Medicare public option, then it would be very clear what the public wanted."

"I understand the aspirational notions around Medicare-for-all, but if there's one thing that I think we still have to wrestle with, it's that Americans want to see more of their fellow citizens covered but they are very nervous about losing what they have," says Sen. Mark Warner (D-VA). "There's a huge risk aversion."

Brown, who has long supported single-payer, agreed. "I think you want people to have choice still," he says. "You don't want to take people's insurance away. A lot of people don't want government insurance. I understand that."

Single payer supporters like to argue that the energy is on their side, that the public broadly supports their plans, and that incrementalism has proven disastrous as both politics and policy. And they can point to polls like the one released this morning reporting that about two-thirds of Democratic primary voters are more likely to back a candidate who supports Medicare for All versus one who wants to expand Obamacare.

But while there's certainly truth to the notion that Medicare for All has risen in prominence and popularity, especially among the left, it also seems clear that there are limits to its rise. A separate poll from Monmouth released this week finds that less than one-quarter of Democratic voters want a system that replaces private insurance with a government-run plan—which is exactly what Medicare for All as envisioned by Bernie Sanders would do. And remember: This poll result is limited to self-described Democrats, who are almost certainly more favorable to wiping out private insurance than others.

Even if Democrats somehow managed to win control of the White House and both chambers of Congress—which looks unlikely at this point—it would be a real struggle to pass the sort of radically disruptive plan that Sanders has called for. And it's not just obstructionist Republicans who won't stand for it; it's Democrats themselves. A decade after Obamacare, it seems that Baucus' intuition that most Americans aren't ready for single payer remains correct.

So yes, Medicare for All has gone mainstream, and yes, it will likely remain a prominent part of the Democratic Party's policy vernacular going forward, and worthy of discussion and criticism as a result. But for the foreseeable future, at least, it will probably remain out of reach.

Show Comments (140)