De Blasio Advisory Group Wants To Abolish Gifted Classes in NYC Public Schools

"It was the year 2019, and everybody was finally equal."

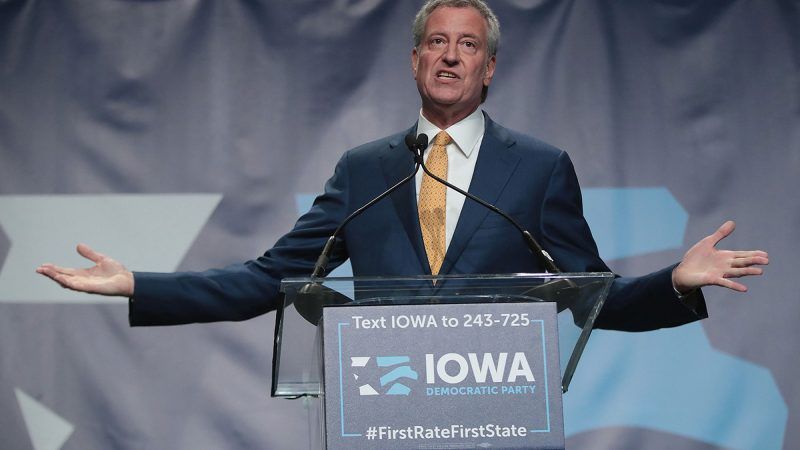

New York City Mayor and 15th-ranked Democratic presidential candidate Bill de Blasio professed his hatred last month for the "charter school movement," "high-stakes testing," and other educational policies bequeathed to him by his reform-friendly predecessor, Michael Bloomberg. Beginning Tuesday, de Blasio, who enjoys sweeping control over his city's school system, has a golden opportunity to act upon his prejudice.

The mayor's hand-picked School Diversity Advisory Group (SDAG) came out yesterday with a detailed set of recommendations to "desegregate" New York's public schools. Among the proposals: Phase out most gifted and talented programs and the tests upon which they are based, eliminate almost all criteria having to do with student performance (for instance, no more auditions for performing arts schools), and radically overhaul admissions policies so that "all schools represent the socioeconomic and racial diversity of their community school district within the next three years, and by their borough in the first five years…[and] the city as a whole" within 10.

That last sweeping item in particular illustrates the overarching goal that dominates discussion of New York's public education system (in which both of my daughters are enrolled). The report, consistent with the advisory group's name and leadership (the three co-chairs are Hispanic Federation President José Calderón, NAACP New York State Conference President Hazel Dukes, and Maya Wiley, senior vice president for social justice at the New School), is fundamentally mobilized around the issue of demographic composition, rather than the problem of school quality.

The most telling statistics concern not the vast achievement gap between, say, charter schools and traditional public institutions among otherwise comparable populations of poor and minority kids, but rather the fact that whites and Asians disproportionately make it through most school "screens," whether they be tests that can be prepped for, or simple attendance criteria that can (with effort) be met.

"The current 'Screened' and Gifted and Talented programs…segregate students by race and socioeconomic status," the report concludes. "Today they have become proxies for separating students who can and should have opportunities to learn together…These programs segregate students by race, class, abilities and language and perpetuate stereotypes about student potential and achievement."

The New York Department of Education, with 1.1 million students (including 123,000 serviced by charters), is the country's largest. It contains all sorts of anomalies, and the gifted and talented emphasis—which kids can start testing for at age four—is definitely one. According to The New York Times, "Last year, New York's elementary school gifted classes enrolled about 16,000 students and were nearly 75 percent white and Asian." This is in a system whose overall ethnic composition is 41 percent Latino, 26 percent black, 16 percent Asian, and 15 percent white, with 73 percent of kids defined as living in poverty. The city's political class has been on its heels ever since an influential 2014 report from University of California, Los Angeles' Civil Rights Project concluded that Gotham is "home to the largest and one of the most segregated public school systems in the nation."

Striving for uniform demographics among schools even within a sub-district, let alone a full district—or borough, or city—requires mandating that more students travel further distances away from neighborhoods that have different racial or socioeconomic concentration than the average. In a city full of ethnic clusters and housing projects, that's basically all of them.

An example: At the elementary school my eldest daughter just graduated from, just 12 percent of the student population either qualifies for free or reduced-price student lunch, lives in temporary housing, or is learning English as a second language. (These proxies for poverty and disadvantage frequently overlap with racial categories, and are routinely—if sloppily—used to measure racial composition.) The combined rate of the seven schools in our area is more like 30 percent, ranging from a low of 11 percent to a high of 100.

To recalibrate the percentage of disadvantaged kids at each sub-district school to between 25 and 35, as is the current goal of the re-zoning process, will require many more 5-year-olds having to travel further than walking distance to kindergarten, in a dense swath of South Brooklyn. When I pointed out at a Community Education Council meeting in June that such increases in travel hassle will necessarily lead to "a lot of unhappy parents," a woman bearing a strong resemblance to Elizabeth Warren snapped back at me: "You mean a lot of unhappy white parents!"

Which is not at all what I meant, though it is representative of the dialogue accompanying these changes—including and especially from district officials themselves.

"I can't tell you how many times I hear in this discussion where there's an equation [of] diversity and a lowering of academic standards," Richard Carranza, New York City's school chancellor, said at a contentious public meeting in May. "I will call that racist every time I hear it…So if you don't want me to call you on it, don't say it." (Carranza is currently being sued for $90 million by three fired ex-administrators who allege his actions stemmed from anti-white bias, litigation that a de Blasio spokeswoman characterized as a "racially charged smear campaign.")

In its brief advocating the discontinuation of specialized schooling, the SDAG cast the very notion of gifted and talented programs as at least abetting overt acts of institutional racism.

"While Brown vs. Board of Education mandated school integration in 1954, gifted programs were used as a method of avoiding required integration," the report stated. "A wave of new gifted programs were founded in the 1970s…This wave also coincided with a number of national resegregation efforts, which used anti-school busing legislation and other tactics to clandestinely reinstitute separated schools."

A layman might read such a formulation as suggesting that gifted and talented programs are a tool for keeping colored people out. In fact, as adopted in New York City over the past three decades, they were an attempt to bring the middle and upper-middle classes back into a public system that they had long since abandoned. And by that standard, the trend was unquestionably a success: School "uptake"—the percentage of resident K-8 kids enrolled in government-run educational institutions—jumped from 67 percent in 2000 to 76 percent in 2010.

But there are different standards in 2019.

As subscribers to The New York Times have come to learn, white and Asian parents are problematic for leaving the public school system (or the city as a whole), but they're also problematic for staying in. "If a substantial number of those families leave the system," noted Times reporter Eliza Shapiro, "it would be even more difficult to achieve integration." And yet:

As the city has tried for decades to improve its underperforming schools, it has long relied on accelerated academic offerings and screened schools, including the specialized high schools, to entice white families to stay in public schools.

But at the same time, white, Asian and middle-class families have sometimes exacerbated segregation by avoiding neighborhood schools, and instead choosing gifted programs or other selective schools. In gentrifying neighborhoods, some white parents have rallied for more gifted classes, which has in some cases led to segregated classrooms within diverse schools.

Eagle-eyed observers may note a crucial gap in the desegregationists' story—did the old system hurt or help students, and will the proposed new system improve on that? Here, de Blasio's SDAG engages in a lot of "yeah, but"-ing.

"Schools with exclusionary screens continually outperform the city mean for academic achievement and graduation rate," the report acknowledges, but that's "due to their selection policies." Sure, "many of these schools have high graduation rates and/or high standardized test scores," but "these statistics are not necessarily reflective of the quality of the school since many of these schools are populated by students who are considered 'high achieving.'"

What about those Asian immigrants who manage to bust ass and have their children succeed? "There are low-income communities, especially in New York City, where families make significant sacrifices to fund test prep and children spend large amounts of time preparing and sacrificing other developmentally appropriate activities to gain admission and do so at an unnecessary cost. This is not equitable even if it is effective for some." (Emphasis mine.)

Conclusion: "Schools that use exclusionary admission models must be reformed if their enrollment policies continue to enact inequity."

Will de Blasio follow the suggestions of his hand-picked panel? It's not clear, though the mayor did adopt 62 of the SDAG's previous slate of 67 diversity recommendations. Regardless, we can see which way the wind is blowing in New York, in other heavily Democratic polities, and maybe in a district near you: Inequality of outcome will be treated as equivalent to inequality of opportunity. Demographic leveling will be prioritized more than improving school quality for all kids.

And if all this effort fails? We'll know who to blame.

Show Comments (87)