Gorsuch and Kagan Clash Over Judicial Deference to the Administrative State

“It should have been easy for the Court to say goodbye to Auer.”

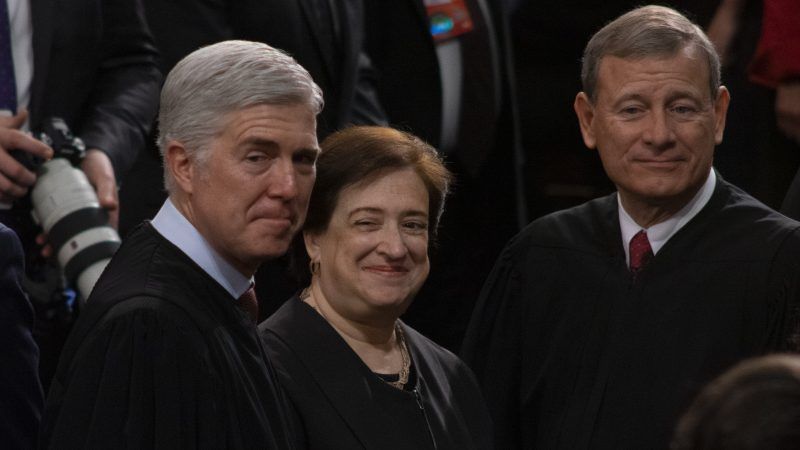

A major conflict is now underway on the U.S. Supreme Court between Justices Elena Kagan and Neil Gorsuch over the issue of judicial deference to the administrative state.

Their division centers in part on whether or not a contentious Supreme Court precedent, Auer v. Robbins (1997), should be kept in place by the justices or struck down in its entirety. In Auer, the Court held that when an "ambiguous" regulation promulgated by a federal agency is challenged in court, the judge or judges hearing the case should respect the expertise of the agency and its staff and therefore defer to the agency's interpretation of its own regulation. An agency's interpretation, the Court held in Auer, is "controlling unless plainly erroneous or inconsistent with the regulations being interpreted."

Last month, the Supreme Court decided a case that asked the justices to overrule Auer once and for all. Writing for a narrow majority in Kisor v. Wilkie, Justice Elena Kagan managed to save Auer from total destruction. "Auer deference retains an important role in construing agency regulations," Kagan wrote. "When it applies, Auer deference gives an agency significant leeway to say what its own rules mean. In so doing, the doctrine enables the agency to fill out the regulatory scheme Congress has placed under its supervision."

Critics of Auer deference argue that the doctrine is tantamount to judicial abdication, that it tells judges to stop doing their judicial duty. Kagan acknowledged those critics, but insisted that the doctrine, while deferential, does still have some teeth. "First and foremost, a court should not afford Auer deference unless the regulation is genuinely ambiguous. If uncertainty does not exist, there is no plausible reason for deference." According to Kagan, Auer "is a deference doctrine not quite so tame as some might hope, but not nearly so menacing as they might fear."

Justice Neil Gorsuch was not persuaded by Kagan's positive view. "It should have been easy for the Court to say goodbye to Auer," Gorsuch wrote. Not only does Auer require judges "to accept an executive agency's interpretation of its own regulations even when that interpretation doesn't represent the best and fairest reading," but the precedent also "creates a 'systematic judicial bias in favor of the federal government, the most powerful of parties, and against everyone else.'"

Gorsuch also challenged Kagan's claim that the Auer doctrine has some judicial teeth. On a daily basis, Gorsuch wrote, federal judges "reach conclusions about the meaning of statutes, rules of procedure, contracts, and the Constitution. Yet when it comes to interpreting federal regulations," he continued, "Auer displaces this process and requires judges instead to treat the agency's interpretation as controlling even when it is 'not…the best one.'"

It is no surprise that Kagan and Gorsuch are now squaring off over this particular issue. In their respective pre-SCOTUS careers, the two figures basically stood on opposite sides of the same general debate.

For example, in a 2001 article for the Harvard Law Review, Kagan, who was then a Harvard law professor, made the case for broad judicial deference not only to federal agencies, but also to those presidents who seek to wield extensive influence over federal regulators. As an example of this phenomenon in action, she pointed to President Bill Clinton:

Faced for most of his time in office with a hostile Congress but eager to show progress on domestic issues, Clinton and his White House staff turned to the bureaucracy to achieve, to the extent it could, the full panoply of his domestic policy goals. Whether the subject was health care, welfare reform, tobacco, or guns, a self-conscious and central object of the White House was to devise, direct, and/or finally announce administrative actions—regulations, guidance, enforcement strategies, and reports—to showcase and advance presidential policies. In executing this strategy, the White House in large measure set the administrative agenda for key agencies, heavily influencing what they would (or would not) spend time on and what they would (or would not) generate as regulatory product.

Under Kagan's view, the courts should generally extend the same deference to such presidential behavior as the courts already extend to the regulatory agencies.

Gorsuch, by contrast, established himself as a critic of judicial deference to the administrative state while serving as a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit. In his 2016 concurrence in Gutierrez-Brizuela v. Lynch, for example, Gorsuch challenged the notion that judges should defer to an agency's interpretation of an "ambiguous" federal statute. "Under any conception of our separation of powers," Gorsuch wrote, "I would have thought powerful and centralized authorities like today's administrative agencies would have warranted less deference from other branches, not more."

In sum, when the next big case testing the bounds of judicial deference to the administrative state reaches the Supreme Court, it will be Kagan and Gorsuch drawing the battle lines.

Show Comments (69)