American Manufacturing Is Growing, but Trump's Tariffs Aren't the Reason Why

A new report shows that American imports from Asia continue to grow, although the tariffs might be responsible for shifting some manufacturing from China to Vietnam and elsewhere.

At the White House's third annual "Made In America" event on Monday afternoon, President Donald Trump singled out a bicycle-maker from Tennessee for special praise. The company, Litespeed Bikes, moved its manufacturing operations back to the United States last year, Trump said, and had seen an explosion in sales since then.

That was evidence, the president said, of "an extraordinary resurgence of American manufacturing."

"When I took office, I was told by the previous administration that manufacturing jobs would be disappearing," Trump said. "There was no way. They said you'd need a miracle."

It's true that American manufacturing has enjoyed a rebound during Trump's tenure, with more than 500,000 new jobs added in the sector. But while that increase is something to be celebrated, a new report finds little evidence of so-called "reshoring"—that is, of jobs being brought back from overseas, something Trump promised would happen as a result of his tariffs on Chinese-made goods.

In fact, more than a year after the first round of tariffs on Chinese imports took effect, the growth of imports from Asian countries to the United States increased by 9 percent in 2018. That's the largest annual increase in more than a decade, according to analysts at A.T. Kearney, a manufacturing and trade consulting firm that publishes an annual "Reshoring Index."

That index—which measures domestic manufacturing of consumer goods against imports of the same products from 14 lower-cost countries in Asia—fell for the third year in a row, which shows that manufacturing firms continue to view Asia "as a more desirable location than the U.S. to produce or purchase a wide variety of goods, notwithstanding the trade measures emanating from Washington, D.C.," the analysts noted.

The report says Trump's trade policies have had a "backfiring" effect on U.S. manufacturing. Although the tariffs were intended to bring jobs back to America, the data indicate that the higher costs created by tariffs have not outweighed the benefits of manufacturing in lower-cost countries. If anything, higher input costs have harmed American manufacturers who import component parts. American audio equipment companies, like Seattle-based AudioControl, might import electronics from China and assemble finished products in the U.S. The company's CEO, Alex Camara, says he's been forced to raise his own prices by between 8 and 12 percent.

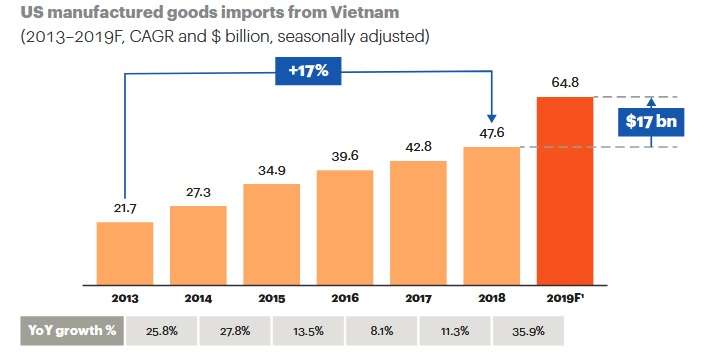

In some cases, the tariffs have encouraged manufacturers to shift production to India, Vietnam, and even Mexico to avoid tariffs—but that's merely an acceleration of shifts that were already ongoing before the trade war, A.T. Kearney's report notes. Vietnam's exports to the United States have doubled since 2013, for example, but the rate of growth skyrocketed during the first quarter of 2019.

Still, China remains by far America's biggest source of imported manufactured goods. Of the $816 billion in Asian-made goods tracked by A.T. Kearney during 2018, about two-thirds came from China.

It may seem pedantic to point out that Trump's tariffs aren't the cause of the manufacturing jobs boom that the president like to talk about. But it matters. American consumers and businesses are paying higher prices as a result of Trump's trade war—and even industries that were supposed to be protected by those tariffs now seem to be losing. If the tariffs are not helping the ongoing resurgence in American manufacturing, why should the president continue to force those taxes on Americans? Unless he's secretly trying to make Vietnam and Mexico great again, the tariffs seem to be failing to achieve one of their primary policy aims: bringing jobs back to the United States.

Trump should enjoy his manufacturing boom while it lasts—because he's not helping it. In fact, the A.T. Kearney report warns, the tariffs might end up having the opposite effect from what was intended. As tariffs increase costs for American manufacturers, they might make CEOs "more likely than ever to orient supply chains" towards lower-cost countries in Asia. And the longer American companies are subjected to higher input costs because of tariffs, the greater risk there is of an economy-wide slowdown.

"If increased tension between the US and its trading partners persists or escalates," the A.T. Kearney analysts warn, "we may simply be seeing the first harbingers of a considerably darker scenario."