The Fight Conservatives Are Having Over Theocracy and Classical Liberalism Obscures How Beaten Their Movement Is

The postwar era has been an endless series of rebukes to social conservatives—and a win for libertarians.

Watching an ugly, name-calling rift on the right between theocratic Catholics on the one hand and classical-liberalish evangelicals on the other, you could be forgiven for thinking that the conservative movement still has some intellectual life left in it. In the scant week since New York Post op-ed editor Sohrab Ahmari attacked what he called "David French-ism" in a bilious article for First Things, the internet has exploded with dozens of pieces on the matter, including a long column in The New York Times by Ross Douthat, a detailed explainer in Vox by Jane Coaston, and an hour-long discussion of the stakes on a recent Reason podcast featuring Katherine Mangu-Ward, Peter Suderman, Matt Welch, and me.

But the deeper effect of the ideological slap fight is to underscore how social conservatives have lost essentially every culture-war battle they have prosecuted since the modern conservative movement got started with the launch of National Review in 1955. Whether they want to use power of the state to compel or restrict certain behaviors (as Ahmari argues) or believe they can win debates in a noncoercive marketplace of ideas (as National Review's David French, the specific target of Ahmari's ire, posits), both sides have wanted the same basic social and cultural outcomes over the past several decades, including a rejection of marriage equality, a ban on abortion except to save the life of the mother, the continued prohibition of most or all currently illicit drugs, an end to no-fault divorce, restrictions on the number and variety of immigrants, tighter controls on whatever they deem to be obscenity and pornography, a bigger role for religion in the public square, and an embrace of what they consider to be traditional sexual mores, marriage conventions, and gender roles.

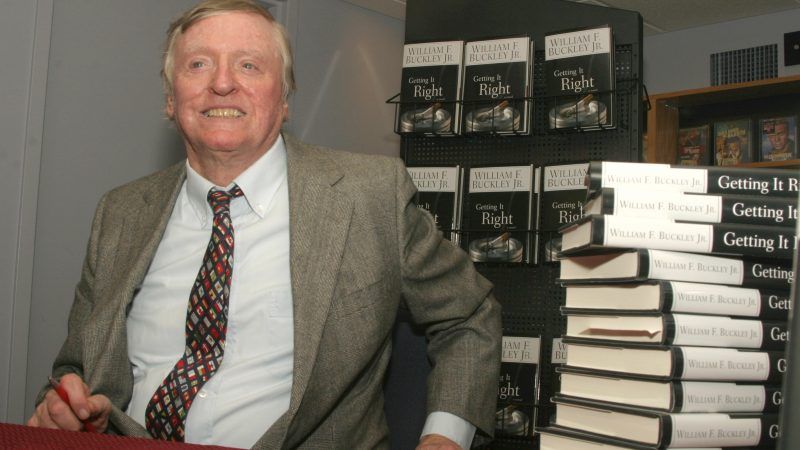

The most you can say is that conservatives may have slowed down social trends, thus validating National Review founder William F. Buckley's cri de guerre that conservatives existed to "stand athwart history, yelling Stop." In the mid-1950s, Buckley targeted "liberal orthodoxy" and "relativism" as the immediate domestic enemies to be engaged. Writing a few months after the 9/11 attacks and after the capture of John Walker Lindh, the "American Taliban" soldier who was raised by hippies in Marin County and captured fighting against U.S. forces in Afghanistan, National Review's Jonah Goldberg identified "cultural libertarianism" as the real problem:

Cultural libertarianism basically says that whatever ideology, religion, cult, belief, creed, fad, hobby, or personal fantasy you like is just fine so long as you don't impose it on anybody else, especially with the government. You want to be a Klingon? Great! Attend the Church of Satan? Hey man, if that does it for ya, go for it. You want to be a "Buddhist for Jesus"? Sure, mix and match, man; we don't care. Hell, you can even be an observant Jew, a devout Catholic or a faithful Baptist, or a lifelong heroin addict—they're all the same, in the eyes of a cultural libertarian. Just remember: Keep it to yourself if you can. Don't claim that being a Lutheran is any better than being a member of the Hale-Bopp cult, and never use the government to advance your view. If you can do that, then—whatever floats your boat.

As I argued at the time (and continue to do so), this is a serious misrepresentation of libertarian thought, especially regarding the right to question and critique the sagacity of other people's freely chosen decisions. (Any meeting of 10 libertarians will yield twice as many opinions about any topic.) For instance, granting freedom of religion, a core libertarian and classical liberal value, in no way implies that you're not allowed to question other people's theology or life choices. If anything, it may demand it. The same goes for the choices that particular businesses make. I believe that as a matter of law, Facebook and YouTube should have the right to adopt whatever content-regulation policies they wish, but that hardly stops me or anyone else from criticizing their specific choices, many of which are stupid beyond words.

But Goldberg was right to identify libertarianism, rather than liberalism or even progressivism, as the true engine of social change. Thanks to the rise of cheaper and better means of self-expression (most notably the internet), American cultural production and consumption has boomed and everything become more individualized and personalized. Since Goldberg's column, it seems inarguable that American culture has evolved in an increasingly libertarian direction, one that grants the individual, rather than the group, what Friedrich Hayek called in The Road to Serfdom "the opportunity of knowing and choosing different forms of life." Even in an age of political correctness, one in which governments, corporations, and social movements are constantly trying to surveil, nudge, and scold people into particular types of approved or "appropriate" behavior, we all continue to be that scourge of 17th-century England, masterless men and women who refuse to conform to what our political and social betters demand of us.

On the issues that conservatives especially care about, we are becoming increasingly secular, accepting of same-sex marriage, and welcoming toward immigrants even as support for abortion rights remains strong and steady. The recent spate of highly restrictive abortion laws in states such as Alabama moved no less a social con than 700 Club host Pat Robertson to say, "I think Alabama has gone too far…I think it's an extreme law." Far from indicating a groundswell in support, such laws, which will all be challenged on legal grounds and almost certainly struck down, suggest the death throes of a social movement that knows it no has chance of success.

We can put too much weight on coincidences, but it's striking to me that just as internecine warfare was breaking out among social conservatives, Jonah Goldberg filed his final column for National Review, where he worked for the past 21 years. He had previously announced that he and former Weekly Standard editor Steve Hayes were starting a new venture that is slated to come online later this year. Goldberg is hardly a stand-in for all of conservatism, but he is surely one of the most thoughtful and representative voices of that broad movement. (So, too, is Hayes, and the weirdly rapid demise of The Weekly Standard is one more indicator that the conservative movement has serious problems.) While conceding that he doesn't think "Sohrab's utopian society, if achievable, would be such a terrible place," Goldberg embraces something that sounds more than a little like the "cultural libertarianism" he once denounced:

Send power back to the communities where people live. If North Dakota wants to be a theocracy, that's fine by me as long as the Bill of Rights is respected. If California wants to turn itself into Caligula's court, I'll criticize it, but go for it….

And the glorious thing about this kind of pluralism—i.e., for communities, not just individuals—is that if the community you're living in isn't conducive to your notion of happiness or virtue, you can move somewhere that is. We want more institutions that give us a sense of meaning and belonging, not a state that promises to deliver all of it for you.

People are misdiagnosing the problem of social, institutional and familial breakdown. A healthy society is a heterogeneous one, a rich ecosystem with a thousand niches where people can find different sources of meaning or identity. A sick society is one where people find meaning from a single source, whether you call it "the nation" or "socialism" or any of the other brand names we hang on statism.

Or from work, gender, sexual orientation, the family, religion, ideology—you name it.

In "Why I Am Not a Conservative," his postscript to The Constitution of Liberty (1960), Hayek posited that a major dividing line between conservatives and libertarians (professing an intense dislike of the word libertarian, he used the term liberal) revolved around a fear of the future. Socialists and libertarians, wrote Hayek, were forward-looking in a way that conservatives were not. Conservatism "by its very nature it cannot offer an alternative to the direction in which we are moving. It may succeed by its resistance to current tendencies in slowing down undesirable developments, but, since it does not indicate another direction, it cannot prevent their continuance." Although Hayek was speaking of an older European vision of conservatism, his insight holds increasingly true for contemporary American social cons, who are simply more and more out of step with what most people believe or want out of life.

Especially in a world in which the progressive left is spending increasing amounts of time and energy trying to police not just our economic choices but our speech, thought, and all aspects of our lifestyles, the libertarian alternative is more appealing than ever. It offers "a rich ecosystem with a thousand niches where people can find different sources of meaning or identity," where we can learn from one another, and have the space to experiment with who we are becoming.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Nick, your party's VP candidate in 2016 would rather run for a party he thinks is inherently racist than run as a fucking Libertarian.

LIBERTARIAN MOMENT~!

Repbublicans and conservatives are beaten. That is why Libertarians keep running their loser cast offs and getting less than 5 %. If Nick were an actual Libertarian that might bother him.

Nick has his Coastal Blinders on. Conservatives are firmly in charge, both of government and of social institutions, in most of the country. Progressives rule only in the major cities, the universities, and the federal bureaucracy.

I am not sure if I would go that far but your vision is a lot closer to reality than Nick's. This article is just another example of why reason would be a better much better for it if it re-located it's headquarters to Wichita or Little Rock or somewhere far away from the coasts and university towns.

Never set foot in Little Rock, much less move there. But if Reason moves to the South, I suggest Nashville. I've lived in both places. One is heaven, one is hell.

That's the case for most of the media. Tunnel vision abounds. I love the demand for diversity from industries that are all huddled in tiny areas with people who have basically identical views on most issues.

A Walmart has more diversity, in every possible way, then ANY media conglomerate in the USA.

Nick really needs to read Michael Malice's new book "The New Right".

He is a bit out of touch with what is going on.

However his point that conservatives largely have no ideological direction is spot on. Especially when compared to progressives or libertarians.

If libertarians have a bunch of ideological direction, it shows how useless that is when it comes to winning elections.

You need a direction only if you think it's necessary to go somewhere else. If you believe things are pretty great where you are and you should stay there, no direction is needed.

I dont disagree. But how have we creeped so far left then?

When you compromise from the status quo you inevitably move left. Underlying principles are necessary. This is why Republicans are terrible defenders of liberty. They have no direction they are willing to push, and when they start to, they allow themselves to be beaten back into submission by the left.

Republicans have had no balls for decades. They are starting to grow a pair, but magazines like Reason are partaking in beating them back into submission.

But how have we creeped so far left then?

The childish simplicity of leftism is a much easier sell than principled liberalism, which requires making sacrifices in the name of principles and accepting there will be both winners and losers.

This is why Republicans are terrible defenders of liberty.

...

They are starting to grow a pair, but magazines like Reason are partaking in beating them back into submission.

That's funny, I'd say it's the other way. Libertarianism is all fun and games until somebody calls somebody else a white nationalist. Then we get to separate the

crypto-SJWs and cultural socialistscivil libertarians from the conservatives.Is reason really libertarian though?

The only people in the commetariat that agree with their editorial stances consistently are the trolls.

We had a ton of people just leave a few years ago.

Reason does not reflect libertarianism at all. At best they are neo liberals.

If Gary Johnson and Bill Weld represent libertarians with spines, then GOP members like Massie and Paul must have Ankylosing spondylitis.

At the very least, the GOP has stood for *something* longer than the LP has.

Most of the country lives in large urban centers of over a million people. This is unlikely to change and probably will become an even greater proportion in the future. The time when most people lived in small towns and rural areas is over.

Most people live in cities for convenience and access.

If anything, as tech and transportation and delivery advance, the less people will feel the need to live in cities.

Soon you can have the best of both worlds, unless the progs decide to make every bit of land outside of cities national monuments.

You'd think so...but then you see tech start ups ALWAYS starting up in hyper-expensive cities instead of lower-cost areas that will make growth easier.

Hell, Vox got HUNDREDS OF MILLIONS of dollars, is bleeding itself dry, and it STILL headquartered in Washington DC instead of, say, a hundred miles west where it'd be far less expensive.

Vox and other companies are based in metropolitan areas because they would not get the staff with the bias they require. Most metropolitan areas such as NY, Washington DC and the majority of California are full of progressives.

This is why Clinton lost. She had no understanding or views of millions or people outside of the big metropolitan areas and was wrapped in her bubble along with the vast majority of the media.

Progressives rule in places where most of the population Is located.

Progressives rule where about half of the population lives.

In many states, a large proportion of the people in cities run by progressives leave at the end of their work day and go home to their Republican suburbs, in their Republican townships, in their Republican counties, in their Republican states.

But the Republicans are losing the inner suburbs too..

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/26/upshot/suburbs-changing-midterms-democrats-hopes.html

Suburbs are getting more liberal *except* for NIMBYISM.

What could possibly go wrong if all the left controls is public television, the press, government,education and social media?

Nick's elision of today's neocons and the conservatives of the Goldwater & Reagan era is simply daft.

I do think the Libertarian Party needs to stop nominating Republicans to run for president. It's good to welcome new members from other parties into the LP, but it is embarrassing to keep nominating presidential candidates who were Republican a year before the convention and then return to the Republican party a year or two later.

Then maybe look at getting some LP members elected to the senate, or maybe governor of a state. Or maybe some LP business magnates that aren’t crazy weirdos like MacAfee.

It's because the LP sleeps three and a half years at a time, then wakes up in a start and pushes forward the first person the find to run for President. Then he loses and they all go to sleep again.

Granted, they could have run Jesus Christ as a candidate, and He would still get only 0.5% of the vote. Because it's so much easier to stay home and not vote than it is to take a chance and vote for someone without an R or D in front of their name.

Which is why the LP desperately needs to get involved in local and state politics. Instead of perpetually pinning their hopes on the impossible odds of making it to a nationally televised presidential debate.

If Nick were an actual Libertarian that might bother him.

It's honestly gotta be a joke. Something like 80% of the country is wondering how exactly the left when batshit insane and what happened to liberal democracy. Nick is saying the argument among conservatives between liberal democrats and social conservatives is a sign that the ship has sailed on Republicans.

"But the deeper effect of the ideological slap fight is to underscore how social conservatives have lost essentially every culture-war battle they have prosecuted since the modern conservative movement got started with the launch of National Review in 1955. "

Remember, though --- it is vital (VITAL, Y'ALL!) for the right to CONTINUE doing what has not worked in, oh, 64 years.

Because, dammit, that way is DUE to work, ain't it?

Yeah, insane that some folks might think "Hey, re-thinking strategies might be a solid gameplan now"

Maybe actually taking your own views seriously rather than cowering and apologizing to the liberal elite all of the time might work better.

No joke. We actually try to justify why men have a right to have a view on abortion. We allowed that much idiocy to become ingrained in the minds of influential morons.

"But don't you dislike unaccountable bureaucrats who can dictate your life, Mike?"

Why yes, yes I do. I fail to see how Twitter or YouTube employees stifling the public debate would be PREFERRED to government employees doing it. I, wrongly, assumed businesses would never be able to shoot themselves in the foot to simply pursue asinine goals.

Hey, I was wrong. Companies can be every inch as stupid as governments and when they are REALLY tight with governments, as Google obviously is, they are extremely damaging to your civil liberties.

Know what REALLY protects Americans? Atomized businesses. Companies too small to dominate the world. Lots and lots of companies like that. But even if that is a step too far...some clear and concrete rules that ALL have to play by. The government has protected YouTube et al for decades and how, precisely, has that benefitted me? I don't want them protected anymore. Until they treat a video the way a cell phone carrier treats a cal, they are not a platform.

Arguably, at least in some fields, the solution here is deregulation. I'm thinking primarily of payment processors. AML/KYC is rather complex to comply with, and really helps put up a barrier to newcomers.

But I am constantly informed that if the market decrees something, even if it is a few Orwellian corporations having enormous influence on society and greatly restricting our freedom, it is the moral judgement of the Gods and cannot be undone.

even if it is a few Orwellian corporations having enormous influence on society and greatly restricting our freedom

This is not a natural market state. Coercive monopolies will never exist without a government's guns to enforce them. If the tech companies are near-monopolies, then there is a problem with the regulations or a problem with the way intellectual property is being adjudicated. Follow the lobbyists - follow the money.

Yes. Once a company gets that big regulatory capture allows them to destroy anything resembling a free market.

Reason seems to think that large companies are capitalist.

Hardly.

You will not find a bigger foe of capitalism than a large company that has "made" it. They ALL seek strong protections from rivals, which is kind of one of the KEY aspects of capitalism.

Google hates capitalism a LITTLE bit less than Communists...but only a little bit less.

I would quibble only to say that it's free markets that large companies hate. Free markets threaten market share, and hence capital. That's the locus where capitalism is the enemy of free markets. Like in China.

That's a definitely more apt statement. They like capitalism because they feel it means they can keep the money. Free markets, you're right, they utterly despise.

No argument.

you know who opposes --- rigorously so --- any attempt to rectify this?

"Libertarians".

"Don't do away with Section 230!" they shriek...as if anybody is advocating that. We are advocating ENFORCING it. Be a platform...get protections. Be a publisher...don't get protections. Allowing YouTube to be a de facto publisher WHILE getting the benefits of a platform is horrifying.

Section 230 doesn't say what you think it does.

Section 230 absolutely allows the private company to moderate however they see fit- whether they have a viewpoint or not. If a forum wants to be a place where only liberal (or conservative) view points are allowed, they are welcome to do so.

Section 230 applies to any platform where its employees do not produce the content. That they heavily or lightly moderate that content- even for a specific viewpoint- has nothing to do with the protection.

And by the way, if you think for just a few minutes about that, it is a good thing. A company SHOULD be allowed to start up a "Conservative Twitter" where only conservative opinions are allowed. And they should be allowed to create a libertarian YouTube or a liberal MySpace.

YouTube produces content.

Section 230 doesn’t say what you think it does.

It says exactly what I think it does and it's a special protection that is a violation of the 1A. Otherwise, you would be able to explain why a section 230 is necessary for digital media but not for print media and how we got through 200+ yrs. of media distribution and 75+ yrs. of radio broadcast without it.

Even if common carriers needed protection in this form, it should be dictated by courts and/or at the state level. Congress can't say who can and can't be sued for speech a priori. If Brandon Eich makes a 'Conservative Twitter' and then starts a business that sponsors people to post, including libel and falsehoods, to 'Conservative Twitter' he damn well should be at least in part legally culpable for the damages.

The idea of common carrier protections is, to a degree, inherently anti-libertarian. When we were talking about water or people would die of thirst and electricity or people would freeze to death there's arguably a moral case or obligation but high speed internet (and "unbiased" at that!) as a human right? Fuck that noise.

Section 230, explictity, only protects moderation done in good faith. The words "good faith" are right there in the statute.

Arguably, until a few years ago, the social media platforms WERE moderating in good faith, or at least you couldn't conclusively prove bad faith. Sure, given who they tended to hire, errors in moderation went almost all in one direction, but they were still errors.

This is no longer true. For at least a couple years now, and to a rapidly escalating extent lately, these platforms are abandoning even the pretense of good faith in their moderation efforts. They're deplatforming and demonetizing the right on a wholesale basis, often using fraudulent claims of pornography, advocacy of violence, and so forth.

If they'd done this with a Democratic administration in power, they'd still have been violating the explicit terms of section 230, but they'd have been safe to do so.

But, no, they're doing it during a Republican administration, pretty openly in an effort to END that administration. And if the Trump DOJ decides to go after them, they'll have the law on their side.

Why is it 'horrifying'

YouTube launched in 2005. It has been around for decade. Not decades.

One of the things I learned from The Conservative Mind is that conservatives always lose. They're like Poland.

They are just playing the long game.

We could blame the Russians, we could point out the futility of international organizations, or we can say that France got tired of being the policemen of the world.

https://www.nytimes.com/1863/11/22/archives/napoleon-and-poland.html

The King of Italy may be sufficiently obsequious to his French patron, but, is it probable that the Pope will place at the mercy of a secular tribunal the sacred interests of the Catholic Church, or that Germany will submit to the consideration of a heterogeneous assembly, an affair which she has so much at heart as that of the Duchies -- or that the Emperor FRANCIS JOSEPH will consent to allow a European Congress to decide whether Austria shall any longer exist as a first-class Power? And if neither of those will assent to the convocation of a Congress for the solution of their difficulties, what will it profit to open a correspondence with the Czar on the subject of arbitration? -- or what prospect will there be of the scheme of NAPOLEON being realized?

Under these circumstances, he will find himself and France still in their old dilemma, with Russia better prepared than ever for war, and no alternative for his dynasty and his nation, save a single-handed conflict with their Titanic adversary, or -- "[???]".

Conservatives are sort of bound to lose a lot. It's built into the whole worldview. Conservatives want to conserve things and resist change. But things always change.

That's also why conservatives believe wildly different things depending on the culture and context they are in. American conservatives have some idea of liberty and self reliance that they hold onto (among other, sometimes more debatable traditional values). But a lot of European conservatives are closer to monarchists or authoritarians. Because that is the traditional order in those places.

This is also why I think the endless debates over whether Nazis are left wing or right are entirely silly. It depends on where you are looking at it from and what the context is. Nazis are pretty left-wing from a contemporary American perspective. But in Germany in the 30s they were the right wing to the communists' left. Or at least I don't think that's an unreasonable way to look at it. They were looking to restore the glory of a powerful German state.

Oh Zeb, the Nazis were never on the same side as the old families of aristicrats. Its why the Von whatevers of Greater Germany viewed Nazis as revolutionary thugs. Some did join the Nazis to play out tough guy fantasies. Goering comes to mind.

Nazis used old German symbols and history for propaganda to get Germans to feel good about doing bad things for the state under some twisted nationalistic motivations.

Social conservatives have learned to relax and let the Democrats do the heavy lifting for them:

https://local.theonion.com/conservative-floridian-enjoys-living-under-sharia-law-m-1830188924

HA!!!!

http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2019/06/07/ex-minneapolis-cop-sentenced-12-5-years-murder-unarmed-woman/1382798001/

Cop murders a woman in cold blood and gets 12 and a half years. He will be out in 8 for murder. At least they convicted him rather than permote him like they usually do. But 12 years for murdering a woman in cold blood is a disgrace.

12 years is a very harsh sentence. It's only because we're inured to incarceration in this country, being by far the world's most incarcerating nation, that such a severe sentence might seem light to some of us.

That is actually a fair point. I think 12 years is a harsh sentence, if he were a thief or the woman hadn't died. But 12 years is a joke of a sentence for murder.

I did a quick search. The average sentence for murder in the US is about 23 years. The average murder sentence in the UK is about 16 years.

23 years for the US? Where did you find that? That sounds very low. I would like to see that.

Average sentence or average time served, I wonder. And what crimes exactly are included.

Whatever you think of the harshness of the sentence, it is incredibly lienient compared to what he would have recieved had he not been a cop.

Unjust and uneven application of the law will be noticed by citizens. When they do, that's when trust in your institutions erode and cynicism begins to set in.

Some examples include: Hillary's emails (and he subsequent melt down and the rise of the 'remove the EC' movement for political reasons), Mueller (and his recalibrating of concepts. E.g. 'We couldn't prove innocence!'), Smollett and now VoxAdcolaypse with Youtube are three prime examples of how the law - or policy in private settings with Youtube - is used to be unjust.

True in some respects. But given that places like the UK actually prosecute for fucking speech...I'll still take the USA.

Hm, I am not sure I completely agree with this assessment. In some ways, things are better from the libertarian standpoint, mostly on social issues. That is a good thing. However, I don't think it has much of anything to do with libertarianism at all. It's not based on the right to conduct your life as you wish, but rather the emergence of support for certain things that used to be shunned and are now fashionable. My evidence for this is that in other regards, support for freedom is declining fairly seriously in the US. Support for privacy, whether it be in our chats or in our financial transactions, is all but gone. Economic freedom is on the decline as well, in both policy and culture.

I believe there are some people who genuinely support some of these social freedoms as freedoms (and not just as fashion), but don't regard the others (like privacy and economic freedom) as important or on the same level, but I am not sure where those people are.

I don't see how we are any freer today than we were 40 years ago. In the 50s and 60s then end of segregation was a real advance in freedom. But how are we more free today than we were in the 70s after all that happened? In some ways we are but in most ways we are not. We live in a very puritanical society where art is self censored, and people see their lives ruined over a single statement on Twitter that is deemed unacceptable to the mob.

Meanwhile, our privacy has erroded to virtually nil. We tolerate things like security searches at airports that would have shocked the conscience of our grandparents. Pretty much every aspect of our life is subject to inspection by the administrative state.

The only way you can say we are more free today is if your standard of freedom consists entirely of abortion, pot, gays, and porn, which come to think of it is Nick's view of freedom.

You forgot Mexicans.

He also forgot food trucks.

Mexican food trucks?

Luz Verde Tacos a Go-Go.

I think you are right. Culturally, we are in as you say a puritanical society. Legally, many things to enhance your privacy are at best viewed with suspicion. People unknowingly generate massive data trails of their activities. And on the economic freedom front, does that much really need to be said?

Even in a more colloquial sense, "does the average Joe feel free," I think he would feel much less free now than in the 70s. Maybe I'm wrong about something, though

Actually, as an addendum I will say that I think economic freedom did improve for a while in the 80s and 90s. Airline and trucking deregulation and financial services deregulation are two examples.

SLD that I use the term deregulation loosely.

...three examples. Need an edit button

Economic freedom absolutely did. But social freedom stayed about the same and then declined significantly after the turn of the century.

The classical libertarian concept of freedom as privacy and autonomy sort of peaked in the Reconstructionist Era. Progressives rebuilt the engine of government to attack groups that were outside the mainstream. After WWII, those groups started fighting back. Their fight was lead by self-interest, which is why it lead to identity politics and freedom for specific oppressed groups. Now it's time to remind Americans that we can skip the entire debate about which groups are OK and simply mind our own business. The tolerance of libertarians often means being passionate about doing nothing.

Completely agree.

40 years ago, you didn't have people working REALLY hard to fuck with your life. You could make a joke and not have your life ruined. "That happened years ago" was actually a valid defense for somebody bitching about some idiocy.

In the 1980's, the government didn't have the capacity to know where we were, every minute of every day.

In the 1980's, the idea that a state would try to fuck over a baker for the crime of turning down business from a gay couple would have been laughed at.

In the 1980's, you wouldn't have a "media" company (whose demise came far too late) obsess over a joke a young woman told before a trip and proceed to utterly destroy her life while she was on a flight.

In the 1980's, you'd realize that airlines have a WAY more intense interest in protecting its passengers than the government and a government monopoly in handling security would be retarded.

Times change, it seems. I guess this is freedom now.

Nick is showing where his priorities are. And it is not anything economic or based on freedom. It is a purely hedonistic pursuit. Which is fine for him. But let's not pretend he has any deep thoughts on society at large. He's demonstrated, repeatedly, that he does not.

Nick has been asleep under Fonzie's ski ramp for a decade now

it seems inarguable that American culture has evolved in an increasingly libertarian direction, one that grants the individual, rather than the group, ..."the opportunity of knowing and choosing different forms of life."

AYFKM?

What group(s) you belong to defines you entirely today. Moreso than any time since the 1800s. And the rights of certain disfavored groups are under swift and unrelenting assault on all fronts, culturally, economically, and sadly still in government policy.

Women have more options in life than 40 years ago. Most people don't care if you are gay and sodomy isn't illegal.

Pot legalization is something, though it's not being done in a libertarian way.

Otherwise, I can't think of many ways we are freer. And there are lots of ways we are less free. Though I do share a bit of Nick's optimism that technology will enable people to be more free in many ways even if government doesn't like it. He does get carried away, though.

John is right Even abortion became de facto legalized by Roe v Wade in 1973. Gays already had their Stonewall uprising in 1968. Hard porn was outlawed some places but I can't recall any sex offender registry. You could get on an airplane without waiting in line to be patted down. Nobody demanded special pronouns to be addressed by. You could smoke in restaurants but couldn't bring your comfort animal with you. As far as personal freedom, the 70s was probably the pinnacle.

@John

"I don’t see how we are any freer today than we were 40 years ago. "

40 years ago:

40 years ago sexual discrimination against women in the workplace was absolutely rampant. In 1978 you could still get immediately fired for getting pregnant or getting married, even for an office job and no one blinked. In 1974 women still couldn't get credit even if all other factors were equal. In 1975 Texas was the first state that allowed a woman to sue her doctor for messing up a childbirth. In 1977 (one for men) a law providing men less protection as surviving spouses than women was struck down. In 1979 (another one for men) a Missouri law allowing women to exclude themselves from jury service at will was struck down. Only in 1981 was workplace sexually harrassment considered employment discrimination. In 1983 Washington excluded its exceptions for marital rape. In 1984 Minnesota overturned it's law which did not allow women as members of the chamber of commerce.

There's a lot that made things freer in the last 40 years.

You realize that discrimination is an aspect of freedom? It represents people being allowed to make choices.

Sure, it sucks when somebody makes a choice that's disadvantageous to you, like firing you because you are predictably going to stop being reliable about showing up for work.

But it sucks in a somebody else exercising THEIR freedom sort of way.

So, yeah, in some ways things have improved, in some ways, even ways you obviously approve of, we're less free today.

A conservative is someone who believes that to ALLOW something is to APPROVE it. The corollary to that is that CRITICISM=INTOLERANCE.

LOL. Progressives are the most conservative of all?

At the extreme, yes. The left-right continuum is a circle.

I'm not even sure it works as a circle. It is more like an open field with "opinion booths" all over it and everyone buzzing around picking random ideas and beliefs from each one.

To consider one single group, anti-vaxxers hold varying beliefs on everything from creation theology to evolution to "a woman's right to chose" to "life begins at the first stirring in the loins of lustful sex partners" . They might be pro-"healthcare is a right" to anti-any regulation of medical care in any form at all. The may be die hard socialists or rabid capitalists. The may be pro- or anti death penalty.

People pick and choose their beliefs from a virtual cafeteria of belief systems and to expect ideological consistency from the unwashed masses is a fool's errand.

Only in the intellectually rigorous (and those suffering from OCD) will you find any kind of ideological purity.

It is not a circle.

There is no way that support for individualism, no matter how extreme, becomes collectivism and vice versa.

The idea that it is a circle was created so that the far left (international socialists/communists) could pin the crimes of another set of collectivists (national socialists/fascists) on the individualist ideologies.

You cannot get to fascism or national socialism by following individualist principles.

It's a circle with individualism/classical liberalism and totalitarianism 180º apart. If you start from liberalism, you can go around the circle to tyranny by going either left or right.

check your premises

Progressivism is the road to communism.

But there will be free porn and pot in the camps. And gays will be able to share a cell with their partners, and lots of fresh air, clean living, and reeducation.

Free porn and pot? Sounds tempting!

Better than no porn or pot.

Off Topic:

https://spaceflightnow.com/2019/06/07/nasa-unveils-plans-to-commercialize-low-earth-orbit/

I'm not generally a fan of Trump's bluster concerning trade and spending. However, put this one squarely in the positive column for the Trump administration.

Obama was pretty good on that issue as well.

Yeah commercial resupply and crew were really good steps. There's just a whole lot of bureaucratic inertia and congressional pork working against this. Hopefully it yields results that can't be ignored.

So they're going to transport civilians up there via Russian Soyuz capsules?

Boeing and Spacex should both have operational manned flights to the ISS by early next year. The NASA contracts require transport for four astronauts/cosmonauts, but both capsules actually are designed for six or seven seats. Possibility exists to fly privately contracted passengers alongside agency personnel. They could possibly do completely private flights as well.

It is comical to hear Nick talk about Hayak as some kind of social libertarian. He was nothing of the sort. Hayak believed that societal mores were a product of the collective wisdom of generations and had reasons for existing and positive effects that had been forgotten over the years. It is true that Hayak didn't think the government should enforce morals. But that didn't mean he was a social liberal. He was very socially conservative and rejected the idea that traditional morality should be torn down. I don't think Hayak and Nick would agree about much when it comes to social mores.

I also think that the subject of libertarianism and that of social conservatism are (or can be) orthogonal. Given that it's a pretty core principle of libertarianism that peaceful activities should not be interfered with, there's nothing about it that says that social conservatism itself is good or bad. It just says that conservatism shouldn't be imposed by government.

That is true.

word.

When has "social conservatism" not sought to use government to enforce it's "morals"?

As a political movement, of course it does that. That's what political movements are for. But there are plenty of individual conservatives who don't favor government enforcing their morals on people. Possibly excepting abortion.

John is not among them.

Of course he thinks rescinding the equal rights of gay people is simply small government treating Christians with due respect.

Depends on what it's a right to. If it's a right to force Christians to bake cakes and arrange flowers, it IS simply small government treating Christians with respect.

That's not "equal" rights, by the way: Only a minority of animals are "equal enough" to qualify as 'protected classes' that get to order people around that way. For most people, you walk into a bakery, and they don't like you, you're out of luck. If you're black or gay, suddenly they're in legal jeopardy if they don't want to do business with you.

Stated preferences, revealed preferences, and all that jazz.

Simply put, even the ones who say they don't want government enforcing their morals on people still vote like they do.

Many libertarians, even prominent ones, are personally socially conservative. I'm thinking primarily of the Lew Rockwell-mises.org crowd.

Calling Lew Rockwell a libertarian these days is a bit of a stretch.

Show me the Reason contributors who are, save for Stossel. It remains my belief that personal responsibility and autonomy are core values that both conservatives and libertarians share. The exercise of freedom is twinned with acknowledging and facing the results of your own actions. That Reason seems to drop that consideration is what makes them "libertines" and shallow thinking leftists rather than deeply principled libertarians. They've become little more than leftists with a handful of pet issues

Very well said.

The Fight Conservatives Are Having Over Theocracy and Classical Liberalism Obscures How Beaten Their Movement Is

Holy shit! Kirkland has taken over Gillespie! Or Gillespie is Kirkland? My world is shattered.

Nick's idea that social conservatism could ever be "beaten" in some final sense is comically absurd. Appearently Nick thinks sex and decadence began in the 60s. The pendulum swings both ways. People always have enough of heodonism and look back to try and find a stricter morality just like they always try and break free from a strict society.

The other thing of course is demographics. People from traditional societies are breeding and people in the open west are not. When you combine Nick's fanatical love of open borders with his view of an ever more decadent and open future, you have to wonder what kind of drugs he takes. The must be very good ones for him to convince himself that a society made up predominantly of Central American Catholics and African and Middle Eastern Muslims (which is what the US would be in a few decades if Nick ever got his way) will be even more "free" than society is today.

To further add to this point, I don't think this guy got Nick's memo about the great Libertarian socially liberal future.

http://disq.us/p/22bf82t

Meh,

I had a friend who pointed out to me that the local Spanish newspaper had a picture of the Pope with the article on one page and a picture of a woman in a bikini with the accompanying article on the other page. I responded with, "How do you think Latin families become so big?" Plenty of Muslims like the idea of polygamy and don't mind other men being gay (because the top is "straight", right?) This article about the sex lives of subsaharan men says that they sleep around because society permits it. By American standards, each of those groups has some shocking sex habits. Remember, the religious right in my homeland fought as hard as they could to keep prostitution legal.

From the article:

This explains the Democrats' opposition to Capitalism.

"a society made up predominantly of Central American Catholics and African and Middle Eastern Muslims"

The gender fluid woke white kids in the public schools will teach the Muslim and Catholic Hispanic kids how to love everyone (who isn't a Nazi Trump voter) and they will harmoniously join together in getting all their teachers fired for teaching them evil things like history and science

From todays morning roundup:

"The woke surveillance state welcomes you to Manchester's Gay Village. "Look fabulous, you're on CCTV!"

Nick, you are a FUCKING IDIOT!

Woke surveillance is different. Why would you worry about that unless you were some racist deplorable or something?

By the way, this:

Cultural libertarianism basically says that whatever ideology, religion, cult, belief, creed, fad, hobby, or personal fantasy you like is just fine so long as you don't impose it on anybody else, especially with the government. You want to be a Klingon? Great! Attend the Church of Satan? Hey man, if that does it for ya, go for it. You want to be a "Buddhist for Jesus"? Sure, mix and match, man; we don't care. Hell, you can even be an observant Jew, a devout Catholic or a faithful Baptist, or a lifelong heroin addict—they're all the same, in the eyes of a cultural libertarian. Just remember: Keep it to yourself if you can. Don't claim that being a Lutheran is any better than being a member of the Hale-Bopp cult, and never use the government to advance your view. If you can do that, then—whatever floats your boat.

is a perfectly valid description. Saying 'this is a serious misrepresentation of libertarian thought is an oversensitive rejection by a libertarian who wants to be perceived as an intellectual. Personally, I don't give a shit if I am perceived as an intellectual as long as I am taken seriously. That elitist BS is a big part of the reason why the libertarian party has such a gross split between the people concerned about civil liberties and the ones who just want pot legalized.

Own your dark side and you can rule this place! Why do refuse to learn anything from Trump?

The idea that government should solve every problem permeates all of society. Liberals and big government lovers control our entire culure. Yet, people like Nick think they can change any of that without being subversive and combative.

Having only discovered these forums about 2 years ago, I was not up to speed on many of the inside jokes like Nick getting invited to cocktail parties. After reading:

It offers "a rich ecosystem with a thousand niches where people can find different sources of meaning or identity," where we can learn from one another, and have the space to experiment with who we are becoming.

I get it now.

"Muffy, did you see this latest article? Do invite Nick to the next party, won't you?"

agreed ^^^

>>>National Review's Jonah Goldberg identified "cultural libertarianism" as the real problem

problem?

I always had a problem with the religious right. They were trying to force their moral dogma on me via legislation. Socialist Democrats are now the new religious right.

I wish people would understand that the left-right thing is ultimately just a choice about how to control a mass of people. Being in the center, a compromise between the Royalists and the Proletariat is not better than the extremes. Libertarians need to own the fact that the American experiment provides not just a 3rd option, but a 3rd dimension, not a place that exists on the scale that history has provided.

Conservative - Progressive, we are stuck playing out the 21st century version of the French Revolution. If people were just not so fucking ignorant of history, we could have some decent dialogue.

what specifically?

Treating marijuana as if it were alcohol was a capitulation by the left. Progressives want to use the coercive power of government to stop people from getting their hands on sugary soft-drinks--and their record on recreational marijuana is like that. Between 2004 and 2008, Barack Obama raided state legal medical marijuana dispensaries in California hundreds of times.

When California and other early states legalized recreational marijuana, it was over the objections of the progressives in Sacramento. That's why they had to do it by referendum. Same thing in Colorado and Oregon. It wasn't until recently that a progressive state legislature would go on the record for legalizing marijuana--and I'm supposed to pretend that its legalization was a victory for liberals over conservatives? I suppose that might be true--if by "conservative" you're referring to progressives who are resistant to change.

Take another "liberal" issue like free speech. Who today thinks that the biggest challenge to free speech is coming from the conservative right? The progressives are practically campaigning on restricting free speech so that people will be scared to say unacceptable things in public, at work, at school, or online. Free speech is more of a conservative issue than a liberal one these days. The prudes who can't stand to let people say offensive things in public are dominating things on the left. Why pretend that's a liberal issue at all?

The "cultural conservatives" of today aren't the people who want prayer and intelligent design in public schools. They're the people writing speech codes at universities in the northeast. The cultural conservatives are the people trying to impose similar speech codes online via Facebook and YouTube. The cultural conservatives are the police unions who undermine Democrat governors trying to legalize marijuana in deep blue states like New Jersey. The cultural

conservatives[prudes] dominate the editorial board of the The New York Timeshttps://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/25/nyregion/new-jersey-marijuana.html

You definitions of what's conservative and what's liberal are outdated if you think they still apply to the same demographics we were using those terms to describe back in the 1980s. The cultural conservatives of yesterday are listening to extreme metal today. Remember how the the pro-Vietnam War liberals holding the Democratic convention in Chicago beat the shit out of the New Left in 1968? The liberals you're talking about are the real cultural conservatives now. You've got your wires crossed, Gillespie. The cultural conservatives with all the power and influence now are the people you're calling "liberals".

"Take another “liberal” issue like free speech. Who today thinks that the biggest challenge to free speech is coming from the conservative right? The progressives are practically campaigning on restricting free speech so that people will be scared to say unacceptable things in public, at work, at school, or online. Free speech is more of a conservative issue than a liberal one these days. The prudes who can’t stand to let people say offensive things in public are dominating things on the left. Why pretend that’s a liberal issue at all?"

Heck, look at the ongoing YouTube controversy. Leftists want to not just de-monetize conservatives (gee, who actually thought Alex Jones was where it would stop? I mean, besides Reason) but to outright deplatform them everywhere. Vox whines that the media isn't able to shut out dissenting views in the news well enough.

Reason would give a more full-throated defense to Larry Flynt's parody of Jerry Falwell then to defend Steven Crowder from trying to have a chunk of his livelihood removed because he hurt the feelings of a dude WHO FUCKING WORKS FOR VOX WHO HAS PLENTY OF MONEY AND DOESN'T NEED A PENNY FROM YOUTUBE. But Reason behaves as if the Vox dipshit has a point. "Yeah, for sure, Crowder was kinda mean to him". I guess free speech is less and less of a libertarian concern as long as it is government supported monopolies doing the silencing.

A lot of people have lost sight of what it means to be "conservative". The word can't mean someone who's easily distracted by religious issues forever. Gay marriage was supported by a majority of white mainline Christians and Catholics in 2011.

https://www.pewforum.org/fact-sheet/changing-attitudes-on-gay-marriage/

People who oppose gay marriage may be more likely to have tattoos and listen to death metal than the average American these days. At what point do these issues stop being an identifier? Cultural conservatism is about using the government to control other people's behavior. That's about the left more than than the right anymore.

We're in danger of ending up like Shrike over in the corner sniveling about Reagan and Falwell--completely irrelevant. Might as well be a redneck grumbling about Vietnam and the dirty hippies. Some people come to Venice beach from the Midwest and think they're going to find hippies all over the place like it's 1969. Sooner or later, I guess we all turn into Disco Stu.

I have an aunt who is a retired CA college professor constantly raving about the evangelicals and how hey control everything. Just completely out of touch.

Look at who wants to criminalize ACTUAL scientific debate and inquiry on Climate Change, if it deviates from the religious orthodoxy

Shorter Ken: "I know you are but what am I?"

> Treating marijuana as if it were alcohol was a capitulation by the left.

Except it's not treated like alcohol. It's why there's still a massive black market in illegal pot in the states where it's legal. It's taxed up the wazoo because the progggies had a wetdream that the taxes would pay for bullet trains.

“It is the job of centralized government (in peacetime) to protect its citizens’ lives, liberty and property. All other activities of government tend to diminish freedom and hamper progress. The growth of government(the dominant social feature of this century) must be fought relentlessly. In this great social conflict of the era, we are, without reservations, on the libertarian side.”

WFB

Where are they now?

Long gone. Libertarians were radicals who had ideals. Old school conservatives were often on the same platform.

Y’all trumpists and apologists for the same are sailing on a different boat.

“Everybody wants to save the world but nobody wants to help mom with the dishes.”

P.J. O’rourke

“Everybody wants to save the world but nobody wants to help mom with the dishes.”

P.J. O’rourke

O'Rourke was Jordan Peterson before his time.

Only with a better sense of humor.

He was more like the Hunter S Thompson of libertarian writing.

Peterson takes himself way too seriously.

Well, taking yourself seriously is kind of his whole message.

He could stand to smile a bit more in public, though.

Well we can’t stay forever Jung.

I guess that beats my joke. I was just going to say that asking him to smile is sexist.

Life is too short to be taken seriously.

Y’all trumpists and apologists for the same are sailing on a different boat.

Y'all might wanna take a look at boat you're on before ya talk. Them skulls and twisted crosses they're paintin' on the sides might not be 'cos they're so metal.

We all might think it's better to sail with an idiot who only gets things right by accident than to sail off after good intentions towards a horizon that's burning.

Just like we're desperately in need of bigger slurs, we're in need of newer, updated terms. As the left has moved further and further left, their attitudes have become increasingly provincial and conservative. They're essentially acting as the Hayekian "social conservatives" of Europe.

The fact is, Libertarians like Reason decided that siding with cultural Marxists was in their best interests. Better we stifle free speech as long as everybody can be FORCED to call a man a woman and vice versa (how can Twitter can somebody for misgendering a "trans" woman --- who, mind you, is biologically male --- by calling it a "he"? It IS a he. Calling it a she is misgendering).

Better to force people to do jobs they oppose than possibly do anything to stop gay marriage from demanding applause (not acceptance).

How often does this site end up on the retarded side of history? They fucking chastised the Covington kids who, LITERALLY, did nothing wrong and their "sin" (not being, apparently, obsequious enough to an elderly leftist moron) was one that Reason SHOULD applaud.

Republicans want to end Obamacare and what is Reason's stance? WELL, YOU NEED TO DEVELOP AN ALTERNATIVE. Not, "It shouldn't be there" or "NO ALTERNATIVE is the better option"...it's "you need to find a large plan to replace this monstrosity with".

Conservatives want to force Google to treat people equally and Reason shrieks in agony.

The only way Libertarians WIN is by living up to their stereotype --- that they are just progressives who want to smoke weed. That is IT. All of the other mumbo jumbo about markets et al is utter bullshit.

Reason staff are not Libertarians. They are anarchists and Lefties hiding as LINOs.

Fonzie is a libertine. Plain and simple. Like how Bill Maher used to call himself "libertarian" a few years ago.

I'd be able to take you more seriously if you didn't use retarded as an all-purpose insult. Any PC concern for the feelings of the developmentally disabled - they are probably not reading this - or those of their relations and friends aside, it shows a paucity of imagination on your part, damikesc.

As compelling as I find minarchism in pursuit of individual liberty to be, the rebuttal to that that keeps people from voting for it that Libertarians have always had to deal with is the complaint that rolling back state control of and interference in the economy will have practical difficulties. In the short term, many people will be not only inconvenienced, but actually harmed: govt employees, and businesses which have units of government as their major or only customers, especially. As perfect a case as I may make for privatizing schools, some citizens worrying about the values of their houses that they paid a premium for because of "the good schools in the district," commingled often with "how will Miss Othmar make a living?"* are not only practical objections, they are emotional ones. Dismantling the Democrats' legislation intruding on the field of medicine will be a similarly emotional fight. Mere "Obamacare repeal" is far from enough. There was plenty of market-distorting state and Federal "law" built up before O took office.

Republicans want to end Obamacare and what is Reason’s stance? WELL, YOU NEED TO DEVELOP AN ALTERNATIVE. Not, “It shouldn’t be there” or “NO ALTERNATIVE is the better option”…it’s “you need to find a large plan to replace this monstrosity with”.

I think Reason is just being a realist regarding this issue. "Repeal and don't even replace it" is political suicide at this point. All the other side has to do is conjure up the usual images of little Timmy dying of some ailment because his family went bankrupt paying for his lab tests and couldn't afford lifesaving surgery or PharmaCorp jacked up the price of his medicine from $10 to $5,000 a dose.

Even if it's legislation curtailing patent restrictions, legalizing foreign prescription drug purchases, prohibiting "certificate of need" requirements or allowing interstate insurance plans, there's got to be some kind of legislation that tells the people we're not going back to the bad old status quo that got us ObamaCare in the first place.

Since when are libertarians supposed to be "realists" in that regard?

Anyway, there were plenty of "alternatives" on offer, just not from the Republican caucus, because they hadn't really intended to repeal Obamacare.

Libertarianism has no record of winning anything unless the right wing or the left wing joins their agenda. They barely win moral victories, and their last one required two of the most personally unpopular presidential candidate in modern history. And GJ nearly blew that too.

It's amusing to see a fractured movement with no discernible presence in national media (Stossel quit ABC decade ago) trying to have some fun at the expense of conservatives having a moment of disagreement.

Do you know why that little spat is making noise? Because conservatism is still a viable and organic movement that resonates will millions of people, even people who aren't SoCons. When pro life and pro choice libertarians debate, no one cares. Of course that's an indication that libertarians are less prone to tribalism, but if you want to make it big, you need passionate who care about the direction of their movement.

Repeating this same "It's a private company" anytime social media deprives content providers of their livelihood is NOT winning. That's like the GOP saying "private market will solve everything" instead of coming up with their vision of market driven healthcare.

I agree, and to be honest I think the bigger concern with regulating FB/Google/etc. is that the regulations will be eminently favorable to the regulated. They have already hired tons of lobbyists, not only for congress but the regulatory agencies. And Zuckerman has announced that he wants federal regulation. After all, what better way to remain a monopoly?

In other words, for those calling for the government to force something to happen, why wouldn't this turn out with a million unintended consequences just like all the other government boondoggles?

It most certainly will.

“Libertarianism has no record of winning anything”

We know.

Go join team blue or red. Warriors or Raptors this year? Better to go with the winners.

Thanks but no thanks. When the choices are between the team of "open border free-for-all" and "everything offends somebody", or "cops' shit don't stink" and "shut up and stand up for the flag", I'm bring a seat cushion for the fence.

It's fascinating to me how many of the previous comments just perpetuate a "conservative vs liberal" view of the world, and don't actually represent an actual Libertarian POV at all.

As long as we continue with this binary way of thinking, and the false perception that "liberal" or "conservative" are the only two options on a linear spectrum, the more things stay unchanged. But many of the comments reinforce something I've been observing for a long time - that a lot of people who love to think of themselves as "libertarian" are really just run-of-the-mill conservatives, and don't actually represent true Libertarian ideals at all.

This comment section is infected with people stuck in the left-right, us vs. them paradigm. Some people just never reach higher than the security/belonging layer of Maslow's pyramid.

From Jonah Goldberg today:

"This brings me back to Tucker [Carlson] and those rallying to his banner. The claim that Washington is run by libertarians makes no sense whatsoever if you define the word libertarian the way libertarians do – or, for that matter, the way dictionaries do. "

Somebody better tell Nick --- perhaps his definition of "libertarian" got mixed up with "progressive" as well!

In practical politics, the socons weren't defeated by libertarians convincing the public that freedom is better than coercion.

If that had happened, we wouldn't just be seeing legalized MJ, we'd be seeing the FDA curbed so people - especially those who are sick or in pain - could have greater right to buy experimental medicines.

We'd see the abolition of any vestiges of the former power of the police and courts to punish healthy adults for consensual sex in private. But we wouldn't see more and more categories of suspect classifications added to the civil rights laws, narrowing the rights of businesses, and we wouldn't be seeing the abrogation of actual constitutional rights (like freedom of religion) in favor of the statutory right to use an unwilling private company's services.

We'd see an end to any War on Porn (William Weld's former claim to fame), or the War on Prostitution, but we wouldn't see people arguing for a right of disabled people to hire prostitutes with tax money.

In short, these victories aren't libertarian victories at all - certain policies have gone out of fashion and others have gone into fashion, but arbitrary government is still in the saddle.

Come to think of it, we haven't seen the end of the War on Prostitution, we've seen a sinister social justice spin put on it, if ENB's accounts are reliable.

You are correct.

And if I remember correctly, didn't William F. Buckley quip something about the left caring more about prostitutes getting minimum wage?

That's what they used to care more about. Now I'm not sure what it is. Feminist identity politics, mostly, I think.

I want to call it "Baptists and Bootleggers", but it's more like "Baptists and Methodists" (or something like that).

Or "Baptists and RadFems".

Come to think of it, we haven’t seen the end of the War on Prostitution, we’ve seen a sinister social justice spin put on it, if ENB’s accounts are reliable.

This is the crux of it.

We're not getting legal pot because the government has no right to say what we put in our bodies--we're getting government approved pot through the expanded bureaucracy set up to monitor pot smokers.

And we're making selling sex nonpunishable.....but buying it is still a crime.

Homosexuals can now register with the government to marry.

These only look like libertarian victories--when they're actually victories for government control.

Now is the time for Reason-style libertarians to reap the reward of their alliance with progressive social liberals.

GILLESPIE: "Hello, comrades, it was a pleasure fighting shoulder-to-shoulder to you against the right-wing theocrats! Now that I've established myself as a reliable ally, I'd like to offer a few ideas..."

PROGS: "Wait, aren't you from that Koch-funded oil-company front? You published articles criticizing socialism and the Democratic Party! Get your corporate shill ass out of our victory party!"

Moar like:

PROGS: "Up against the wall you capitalist running dog lackey. We'd offer you a last vape but the FDA has ruled it is neither safe nor effective".

Even more like....

GILLESPIE: “Hello, comrades, it was a pleasure fighting shoulder-to-shoulder to you against the right-wing theocrats! Now that I’ve established myself as a reliable ally, I’d like to offer a few ideas…”

PROGS: “Wait, aren’t you from that Koch-funded oil-company front? You published articles criticizing socialism and the Democratic Party! Get your corporate shill ass out of our victory party!”

THE PARTY: "Don't worry, Comrades, it will all be sorted out after your de-lousing. Right this way. Follow the Rainbow arrows..."

Reason likes them some of that French sauce.

That musta been some cocktail side deal.

"I am pleased to inform you that The United States of America has reached a signed agreement with Mexico. The Tariffs scheduled to be implemented by the U.S. on Monday, against Mexico, are hereby indefinitely suspended. Mexico, in turn, has agreed to take strong measures to ...stem the tide of Migration through Mexico, and to our Southern Border. This is being done to greatly reduce, or eliminate, Illegal Immigration coming from Mexico and into the United States. Details of the agreement will be released shortly by the State Department. Thank you!"

A big win for the United States! #MAGA

----@realDonaldTrump

https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/1137155056044826626

We can only hope that the agreement includes Mexico agreeing to become a safe third country for asylum purposes.

This win (if it's a win) should give the China deal some momentum, too. Emperor Xi may be shitting his pants right now.

I opposed Trump using trade leverage this way, and even if he wins, I'll be glad if no president ever does something like this again.

If he was right and I was wrong, then I'm glad I was wrong--since me being wrong means that the border is more secure, it happened without a wall being built, it means it happened within the context of the Constitution and our duly ratified treaties, and it means that it's good for the U.S.A. I'm so glad to be wrong.

Hope I was wrong about China, too.

Peace thru superior firepower... if only that potential enemies know you will use it to defend yourself.

China.

You wanna talk defense.

It is California vs Canada now in the NBA.

What is a conservative to think? Who gets invited to the White House for burgers?

Nixon had ping pong with China. Jimmie Carter had hockey with the USSR.

What now, how can we compete with China in the arena? Beach volleyball might work.

Pierre Trudeau had the hockey diplomacy. Carter had the Olympics in Lake Placid, but lost whatever gloss that gave him with the summer games boycott.

+10000000000

Mexico, in turn, has agreed to take strong measures to …stem the tide of Migration through Mexico, and to our Southern Border.

Mexico is paying for a virtual wall.

MAGA!

And let’s hope the safe third country is on there, but it has not been mentioned on any news program.

"[Mexico] turned back U.S. suggestions that Mexico become a so-called Safe Third Country, where migrants would be forced to apply for asylum in Mexico instead of the U.S.

“Bottom line is Mexico has to keep asylum seekers temporarily but not permanently,” said Shannon O’Neil senior fellow for Latin American Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations."

https://www.wsj.com/articles/trump-says-u-s-has-reached-deal-with-mexico-11559954306?

On the downside (from my perspective), Mexico will not be a "safe third country", but on the good side, Mexico has agreed to formalize the arrangement where asylum seekers from Central America wait for their asylum hearing in Mexico.

About 90% of asylum seekers from Central America are either rejected for asylum by the U.S. or never show up to their hearing. They become illegal aliens after they're denied asylum, and their children become Dreamers. If this policy means that 90% of asylum seekers are denied entry to the US as they wait for their asylum hearing in Mexico, then that may be an effective deterrent without being 100%.

The sticking point of the "safe third country" designation from Mexico's perspective may have been that if Mexico were to agree to that, Mexico would be obligated to give all those Central American asylum seekers citizenship in Mexico. Mexico doesn't want to become a magnet for refugees either. They want to keep the option open to kick those people out someday, and they can't do that if they agree to become a "safe third country".

Meanwhile, anyone who opposed Trump starting a trade war with Mexico over this got their wish. No one should both criticize Trump for starting a trade war with Mexico and then turn around and criticize him for not starting a trade war. If Trump capitulated for less than 100% of what he wanted because he thought it was in America's best interests to do so, then that's a good thing. I opposed Trump starting a trade war with Mexico, and I'm glad he backed off.

People who opposed Trump's trade war threat against Mexico who now criticize him for backing down are probably not being honest brokers. That's like criticizing a president for NOT pulling troops out of Iraq and then blaming him for the emergence of ISIS. Can you honestly move from one position to the other without admitting that you were wrong in your initial position? You can say, "I was wrong to oppose Trump's trade war with Mexico, and he should have stuck with it to get a "safe third country" agreement with Mexico, but we can't honestly maintain our original opposition to a trade war and simultaneously criticize Trump for not starting one.

The trade war threat against Mexico was a bad idea for me. It shouldn't be the tool he uses in every international negotiation. It was even more onerous to me since Mexico has been slowly doing things that should be a fair compromise for Tump. A bit of a bad tactic to push an ally with a major threat as they are working with your demands. Results matter and I'll praise the end results if they are positive but hate the tactic

Yeah, I thought it was a bad idea.

I'm so glad there wasn't a trade war with Mexico.

There are people out there arguing against Trump's trade war with Mexico, and there are people who are out there arguing that Trump's trade war with Mexico was a failure. Both of those groups of people are wrong--because there was no trade war with Mexico.

The trade war with Mexico was set to start Monday, June 10, but Trump called off the trade war with Mexico, and I'm glad he did.

I also thought Trump sexually assaulting both Theresa May and the Queen of England was a bad idea, but Trump didn't sexually assault either one of them. The people we see on the news talk shows telling us about how Trump lost the trade war should be aware that there was no trade war and that talking as if there were one is both absurd and dishonest. Being absurd and dishonest doesn't bother them, though. Anything negative you say that's against Trump is perfectly appropriate in their minds--because it's against Trump--honesty and logic be damned.

The boy who cried tariff.

Trump threatened Mexico with the United States losing 400,000 jobs and $50 billion. Obviously that wouldn't be so great for Mexico either, but hailing this as good diplomacy is a stretch.

That's not even mentioning that the underlying goal is to throw a grenade at the Statue of Liberty so Trump's racist dumbfuck base thinks they can keep a few brown people off their lawns.

"Socialists and libertarians, wrote Hayek, were forward-looking in a way that conservatives were not. Conservatism "by its very nature it cannot offer an alternative to the direction in which we are moving."

Not sure this is true. Kirk made a compelling argument conservatives were an impetus for change citing, to name a couple, being early proponents of women's suffrage and abolitionism.

When Hayek speaks of "conservatives", he usually means in the European sense, which is a bit of a different animal than the American variety. Reagan and Bismarck do not have that much in common.

Still waiting on Nick interviewing Peterson.

What are you guys waiting for? I think Gillespie can do a good job while Peterson would likely feel comfortable in a libertarian interview.

Peterson can cross the philosophical divide as he showed with Zizek.

"But the deeper effect of the ideological slap fight is to underscore how social conservatives have lost essentially every culture-war battle they have prosecuted since the modern conservative movement got started with the launch of National Review in 1955."

The Drug War is coming to an end. That is a victory for National Review.

+1

W F Buckley Jr always had a "libertarian streak" in him, having been influenced by The Two Franks, Chodorov and Meyer, but he was also a Cold Warrior and a supposedly devout Catholic. The "fusionism" that NR posited drew on some libertarian principles, but it was always the traditionalism and pro-military statism that drove the bus. Making a "conservative majority" meant throwing scraps to libertarians, and much large portions of the feast to ex-Dixiecrats and socially conservative Catholics and Evangelicals who felt abandoned by the Democratic party, especially from the late 60s on.

Conservatism is young people waiting for old farts to die.

I can't be bothered to rtfa since the premise is dumb. I'll agree that social conservatives have done little more than giving up ground. On some points that is good, but on others it has been detrimental to our culture. Much of their losses can be directly attributed to the control leftists have over communication platforms and the bureaucracy. The remainder of the losses is R reps selling them out.

My bigger issue is the idea that theocratically minded people significantly represent conservatives. Which socon issues equate to theocracy?

The theocracy is mostly interested in imposing religious rules on sexuality. Catholic religious values such as "birth control is abortion" or "have babies or no sex" or "you can't tell your kids birth control exists in public schools". Those are rules that socon legislatures in red states want to institute. That's as least as authoritarian or more as the woke SJWs telling bakers they have to sell wedding cakes to gays.

Excellent article!

this a "joke" post right?

Does not compute.

Some people still haven't accepted the 14th Amendment.

More people than you might worry about still don't accept the 19th.

From a consequentialist viewpoint, the 19th probably was a bad idea.

Pretty much every amendment from the Wilson era could be thrown out and the state of the country would improve immensely.

Not merely from a consequentialist standpoint, but also from structural and process standpoints. Popular election of Senators removed the once voice State governments had at the Federal level.

It was an obviously terrible idea that has demonstrated terrible results.

See ^

Men, history's greatest leaders.