Trump Trade Advisor Peter Navarro Says Trade Deficits Hurt Jobs and Growth. Here's Why He's Wrong.

Navarro's Wall Street Journal op-ed looks more like a deliberately deceptive attempt to argue that limiting imports will boost economic growth. It won't.

President Donald Trump's top trade advisor, Peter Navarro, tried to make the case in The Wall Street Journal yesterday that free trade advocates should hop aboard Trump's trade agenda.

Instead, he ended up highlighting a crucial blind spot in his, and the president's, understanding of the issue—an error that shows exactly why Congress should not trust him, or Trump, with greater powers to reshape global trade.

Most of the op-ed is premised on the idea that lowering tariffs all around the world would be beneficial to the United States' economy. And that's probably true. Trade isn't a zero-sum game, so more trade and fewer tariffs would generally benefit everyone. This isn't a novel idea—it's basically been the consensus among the nations of the developed world for decades, and it's been pretty phenomenally successful—but it is good to hear the Trump administration admitting as much. While Trump has at times talked about trying to get to a point where there are no tariffs at all, his actions (and his general "trade is bad" worldview) make it difficult to take that seriously.

But Navarro is playing a bait-and-switch here. To get to that world of lower tariffs, he says, Congress should give Trump more power to increase tariffs. As a negotiating tactic only, of course. Specifically, Navarro is calling for the so-called Reciprocal Trade Act, which Trump asked Congress to pass at the State of the Union address earlier this year. As I wrote at that time, this bill would effectively give the president more excuses to raise trade barriers and impose tariffs, which are really just taxes paid by American importers.

For example, the European Union currently charges 10 percent tariffs on cars imported from America while America charges only 2.5 percent on car imports from Europe. If the Reciprocal Trade Act were to become law, Trump could circumvent Congress and raise car tariffs to 10 percent—something that he's already threatened to do via a different mechanism, and something that would be disastrous for America's auto dealers and car buyers.

Should Congress trust Trump with those powers? Maybe you believe Navarro's claim that Trump would only use it to negotiate for lower tariff rates for American exports. But even then you should ask—as with all delegations of authority from Congress to the executive—whether you'd want the next president to have that same unchecked power.

You should also examine the argument Navarro makes at the end of the op-ed, where he suddenly shifts into protectionist mode—and ends up undermining his own argument for expanding presidential trade powers by demonstrating how little the current administration understands about trade.

Here's what Navarro writes (bolding mine, italics his):

For a ballpark estimate of the jobs impact from lowering the U.S. trade deficit through a reciprocal tariff policy, the Economic Policy Institute provides this yardstick: For every $1 billion deficit reduction, U.S. employment increases by approximately 6,000. This suggests a [Reciprocal Trade Act] jobs boost ranging between 350,000 and 380,000.

That last claim may disconcert free-trade economists, who insist higher tariffs always result in slower growth and less employment. But because imports don't contribute to gross domestic product, unfair trade reduces growth, and narrowing the trade deficit through higher exports and lower imports boosts growth.

There are two fallacies at play here.

First: Navarro is only half-right when he says that imports don't contribute to gross domestic product, and he's fully wrong to imply that imports harm growth. (In fact, they don't influence the calculation of GDP at all, but they do have a positive correlation with economic growth.) Second: Running a trade deficit or a trade surplus has virtually no bearing on how quickly a country's economy grows. Navarro uses these two errors to build a backdoor case for restrictions on imports that is not grounded in either economic theory or empirical evidence.

Let's start with the first mistake: that imports do not affect GDP, either positively nor negatively. Here's how economists Tyler Cowen and Alex Tabarrok explain this exact error in their book Modern Principles of Economics:

Here is a mistake to avoid. The national spending approach to calculating GDP requires a step where we subtract imports but that doesn't mean that imports are bad for GDP! Let's consider a simple economy where [Investment], [Government spending], and [Exports] are all zero and [Consumption]=$100 billion. Our only imports come from a container ship that once a year delivers $10 billion worth of iPhones. Thus when we calculate GDP we add up national spending and subtract $10 billion for the imports, $100-$10=$90 billion. But suppose that this year the container ship sinks before it reaches New York. So this year when we calculate GDP there are no imports to subtract. But GDP doesn't change! Why not? Remember that part of the $100 billion of national spending was $10 billion spent on iPhones. So this year when we calculate GDP we will calculate $90 billion-$0=$90 billion. GDP doesn't change and that shouldn't be surprising since GDP is about domestic production and the sinking of the container ship doesn't change domestic production.

But not only do imports (or the lack of them because all the container ships sank) not harm GDP, they likely add to it. Cowen and Tabarrok continue:

If we want to understand the role of imports (and exports) on GDP and national welfare. We have to go beyond accounting to think about economics. If we permanently stopped all the container ships from delivering iPhones, for example, then domestic producers would start producing more cellphones and that would add to GDP but producing more cellphones would require producing less of other goods. If we were buying cellphones from abroad because producing them abroad requires fewer resources then GDP would actually fall—this is the standard argument for trade that you learned in your microeconomics class.

This is all a bit technical, to be sure, but it applies to the real world. Last week, I spoke with Alex Camara, the CEO of AudioControl, a Seattle-based manufacturer of speakers and headphones. Although all his company's products are designed and built in the United States, about 30 percent of the component parts are imported from China—and are now subject to 25 percent tariffs. Navarro wants you to believe that those imports are a drag on GDP, but a business like Camara's might not even exist without them.

"Domestic production would not be as strong as it is without access to global supply chains, which reduce costs, raise productivity, expand the global market share of U.S. firms, and allow the United States to focus on what it does best: innovating, researching, and designing the cutting edge goods and services of the future," write Theodore Moran and Lindsay Oldenski, researchers at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. "The data show that when US firms expand abroad they end up hiring more workers in the United States relative to other firms, not fewer."

The second mistake is the more important one, but it builds on the first. Navarro is trying to argue that reducing imports will cut the trade deficit and boost economic growth.

As the Harvard economist N. Gregory Mankiw explained in The New York Times last year, countries run trade deficits because their governments and people spend more on consumption and investment than on the goods and services they produce. The way to reduce a trade deficit is to reduce public and private spending—which is why America's trade deficit has typically fallen during recessions, when spending drops—not by attacking the countries that are trading with you.

"To be sure, I would be happy to have balanced trade," Mankiw writes. "I would be delighted if every time my family went out to dinner, the restaurateur bought one of my books. But it would be harebrained for me to expect that or to boycott restaurants that had no interest in adding to their collection of economics textbooks."

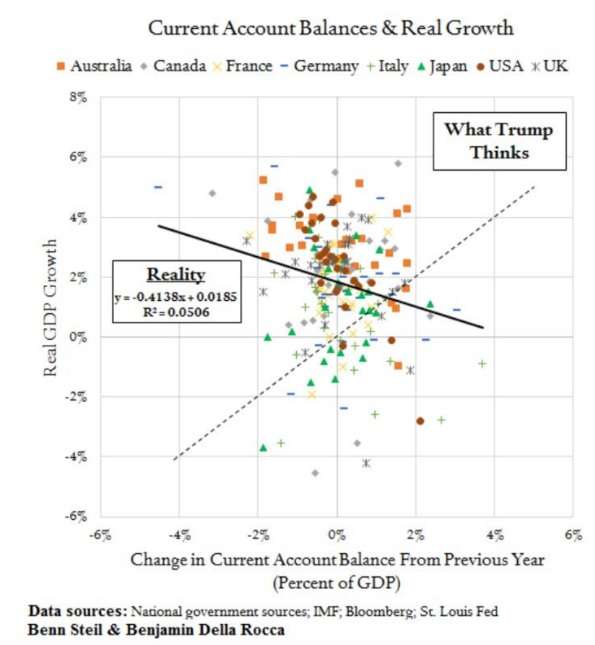

The idea that trade deficits are tied to economic growth also fails in practice.

In 2017, for example, the United States recorded GDP growth of 2.22 percent and ran a trade deficit of about $502 billion—"with a b," as Trump would say. But look at other countries that had similar growth rates. France grew at 2.16 percent but had a trade deficit of $18 billion. Germany grew at 2.16 percent too, but ran a trade surplus of $274 billion.

The same is true at the higher end of the growth scale. Ireland grew by 7.22 percent and had a $101 billion trade surplus in 2017; India grew by 7.17 percent with a $72 billion trade deficit. It's also true at the bottom. Italy's economy grew by a mere 1.57 percent with a $60 billion trade surplus; the United Kingdom grew by 1.82 percent despite a $29 billion trade deficit.

As Benn Steil so perfectly illustrated it in Business Insider last year:

If Navarro were truly interested in building a world with freer trade and lower tariffs, his influence on "Tariff Man" Trump would be welcomed. But his Wall Street Journal argument looks more like a deliberately deceptive attempt to push for greater executive powers over trade, which could be wielded to limit imports into America under the false premise that doing so will boost economic growth.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

According to Boehm, pre-Trump managed trade policy never hurt any Americans -- EVER!

Navarro's Wall Street Journal op-ed looks more like a deliberately deceptive attempt to argue that limiting imports will boost economic growth. It won't.

It has. The US economy has grown stronger over the last 2 years in spite of tariffs and increasing trade restrictions by our trading partners. Even Boehm does not know how long that will continue. Since Boehm lives in TDS fantasyland, he posts nothing but deliberatively deceptive op-eds.

Correlation is not causation. Yes, the economy has grown much stronger during Trump’s first term. But it is much more rational to attribute that growth to the reductions in tax rates (especially in corporate tax rates) and to the reductions in costly and counterproductive regulations. We’ll never know exactly how the country would have fared with the same tax cuts and regulatory overhaul but WITHOUT Trump’s idiotic tariffs and trade wars, but basic economics indicates that we would have been better off than we are. With Trump, we’ve had two steps forward -tax cuts and deregulation - and one step back with the tariffs. Sure, we’re better off now than we were, but we’re worse off than we could have been.

"Correlation is not causation. "

i.e.,

"My theories are unfalsifiable"

Should Congress trust Trump with those powers [to raise tariffs]?

The Founders wouldn't have trusted the President with those powers. Maybe someone around here who Loves the Constitution so much can explain why now we need Congress to cede power to the Executive when the founders didn't see that as necessary?

There is nothing in the Constitution that prevents one co-equal Branch from ceding some of its discretionary power to another Branch.

Congress has the enumerated power to coin money and gives power to the Executive Branch to carry out and enforce related monetary laws.

Congress has the enumerated power To regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes; (Article I, Section 8) and has given the Executive branch the power to negotiate on the USA's behalf.

You didn't answer my question... should they? And if they should, then why didn't the Founders vest that power with the executive in the first place?

Maybe my comment didnt clear it up.

The Founders created a system of government where the legislative Branch makes the laws and the Executive executes on those laws.

That is what the Founders deemed necessary. The Founders also gave very broad discretionary powers to the Executive Branch with a fail-safe being impeachment.

The most fantastic part of the Constitution is that does allow our government to adapt after over two Centuries of a changing World. Congress wanted to give the President power to set tariff rates and negotiate trade agreements. Congress can set trade policy and ratify/reject trade agreements at any time.

I'm not asking you what Congress can do, I'm asking you what you think Congress should do. Trump thinks Congress should give the President broader powers to raise tariffs without consulting Congress through the Reciprocal Trade Act.

My argument is that Congress shouldn't give him more power, in fact they should be taking back the powers to raise tariffs that the Founders (and people) who ratified the Constitution said belong to the people (Congress).

Do you support the Reciprocal Trade Act? I'd love to hear the true libertarian argument for more executive power in raising tariffs.

As I said is the current arrangement, I also want a single person negotiating with foreign nations relating to managed trade policy. Trump is doing that.

If we had free trade, there would really be no details to negotiate anyways.

Its why most corporate boards dont negotiate contracts with other companies. They let the CEO do it and sign off on it or not.

FYI: Congress can set trade policy and bind Trump's strategy at any time that they want to and there is nothing Trump can do about it.

Congress has chosen not to.

For the best most knowledgeable answers -> loveconstitution1789. No sarcasm at all; Have totally enjoyed your comments.

Good point!

Congress has no constitutional power to divest its powers to another branch. Someone who understood the constitution and the concept of separation of powers would know that....

[…] Source link […]

Help me to get this right. If I buy $100 worth of goods from a guy in China and he loses my check and never buys $100 in goods from me, then I've "lost" $100? It seems like I actually "gain" every time I buy imported goods and the foreign guy loves my payment so much that he never uses it.

The U.S. taxpayer pays for Mr. China guys shipping cost to you. China exempts Mr. China from all VAT taxes (shipping to you). Mr. China just dumps his loses onto the U.S. federal debt by means of holding Treasury Bonds the U.S. cannot back but will try to print their way out of.

You confuse trade outcomes with government profligacy and then fail to understand that it doesn't matter WHO buys government debt...

Just so you know, Paul Krugman is 100% on board with Trump on this issue.

The article's conclusion:

And what exactly makes you think that Paul Krugman knows anything about economics? Because all of the recent evidence is against that.

Is that meant to be an appeal to authority, or guilt by association?

Seeing as KrugMAN! thinks it would be swell if aliens came down and broke all our shit in order to boost the economy, I’m gonna go with they’re both retarded?

Stopped watch...

Anyone who is making ANY economic argument by using GDP is a complete moron. GDP is not actually a thing in the real world. It is a bookkeeping entry. And one thing is for certain - everyone who has ever made such an argument has missed everything that is actually important in economic terms.

Current account deficits and surpluses DO matter in an era of floating/reserve currencies. A country that runs perpetual deficits will see their currency decline - which also means that everyone being paid for their labor in that currency is also seeing their income decline in relative terms. However, because current account deficit is fully offset by capital account surplus (again mere bookkeeping entry) while the group of people earning an income in the currency is seeing a decline, those who own assets in that currency are seeing an increase in demand. But those who own assets and those who earn non-asset income are almost NEVER the same group of people.

Reserve currency changes things a lot for the very few countries that have the reserve currency. Too long to explain - but basically those few countries are only able to sustain deficits over time (and that is pretty much only the US and UK) by protecting their financial sector at the expense of every other sector. Which IS protectionism for the industry that produces currency from thin air - at the expense of every other industry that produces something else. And again, those protected are never the same group as those harmed by deficits.

Once you see what is actually happening, then it is no longer real economics but mere utilitarianism. Some may be better off - some worse - and whoever has the power can tell the others to FYTW. That AIN'T economics. Using economic terms to describe that is deceitful.

Current account deficits and surpluses DO matter in an era of floating/reserve currencies. A country that runs perpetual deficits will see their currency decline – which also means that everyone being paid for their labor in that currency is also seeing their income decline in relative terms. However, because current account deficit is fully offset by capital account surplus (again mere bookkeeping entry) while the group of people earning an income in the currency is seeing a decline, those who own assets in that currency are seeing an increase in demand. But those who own assets and those who earn non-asset income are almost NEVER the same group of people.

It seems here you're making an argument about budget deficits whereas this article is talking about trade deficits which are different things. What am I missing in your argument?

Current account deficit is trade deficit that includes both goods and services

Sorry, but there simply is no validity to your claim that trade deficits have ANY connection to a currency's purchasing power. That is solely dictated by the relevant government's monetary policy...

You got the relationship backward.

A current account deficit either corrects on its own via currency float. Deficit turns to surplus turns to deficit so over time the net balance is 'close enough' to zero to be noise. And that also means that sometimes imports/finance is favored, sometimes exports/mfg.

Or monetary policy is used to PREVENT it from correcting. In the case of China/HK/Taiwan, monetary policy is used by their central bank to peg their currency to the dollar. In the case of Germany, monetary policy is used to link their economy to a bunch of deficit countries and handle it as a eruozone instead of a markzone. In the case of Japan, govt debt is used outside Japan for a carry trade. Those are the only countries on the permasurplus side. US and UK are the only ones on the permadeficit side (x India which is a statistical fluke cuz IMF/etc don't know how to account for actual gold in trade).

However, because current account deficit is fully offset by capital account surplus (again mere bookkeeping entry) while the group of people earning an income in the currency is seeing a decline, those who own assets in that currency are seeing an increase in demand. But those who own assets and those who earn non-asset income are almost NEVER the same group of people.

Are the asset holders stock investors, business owners, and real estate holders? And the non-asset holders the checking and maybe savings accounts only?

Basically yes for the first question.

Non-asset holders are basically people who rely purely on income (doesn't matter in this instance whether the source of that income is wages or govt payments). People whose only asset is something they can't really sell or borrow against (eg a homeowner who wants to pay off their mortgage to reduce housing expenses rather than borrow against it to produce/shelter income) are for practical purposes in that second group as well.

"Current account deficits and surpluses DO matter in an era of floating/reserve currencies. A country that runs perpetual deficits will see their currency decline – which also means that everyone being paid for their labor in that currency is also seeing their income decline in relative terms."

Since the Asian Flu of the 1990s, the U.S. Dollar has been the safe harbor currency of the world--despite our soaring budget deficits and increasing trade deficit by way of trade with China.

When it comes to deficits, we may be a horse in line at the glue factory--but we're the prettiest horse in the glue factory.

Plus our horse will always make it to the front of the line at the glue factory.

Its not hard to see all the Socialist horses dying much sooner.

been the safe harbor currency of the world–despite our soaring budget deficits and increasing trade deficit

Our trade (or current account) deficit is actually a NECESSARY (mathematical) precondition to being the reserve currency. That country has to perpetually supply (net export overall) its currency to the rest of the world because that safeharbor or reserve currency is what provides liquidity to others in the event of financial crises elsewhere. For the reserve currency countries (and only them), the 'trade deficit' is not driven by our demand for imported goods but by other countries demand for our currency/liquidity.

Govt budget deficits are actually semi-irrelevant. What matters is the total (private and public) borrowing since that borrowing is what creates the currency in the first place (in a fiat/bank-based money system). If private isn't borrowing to create currency, then public/govt has to otherwise the currency doesn't get created and if its not created then it can't be exported to provide liquidity.

It worked the same way when we had a gold standard. Except that a hard gold-currency link forces entire economies into crisis because the entire money supply gets drained from a country whenever intl trade flows need to be settled in gold. Hard to see unless you are looking at BRITAIN during that era cuz they were the reserve currency then.

When people elsewhere in the world flood into dollar denominated assets, it is not because they're taking our current account deficit into account.

Reality is reality even if it doesn't behave in line with our preferred theories, and a flight to safety is what it is--regardless of where our current account deficit is clocking in at the time.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flight-to-quality

They flood into dollars because:

either a)their own debt is denominated in dollars and so they need dollars for the interest payments and their own trade flows become an uncertain way to guarantee those payments in a fear type environment

or b)because dollars are available and liquid and both of those features are more valued when markets get fearful.

Both of those are only possible because we run current account deficits.

That's what I've been saying too. The trade deficit is not a problem in itself, but it's a symptom of a long-term problem: the sucking of the entire world into this banking scheme, because their local swindle is worse than this worldwide swindle.

If there were any banking system in the world that wasn't based on government fiat, it would get the business, and this dollar swindle would end, along with the large and persistent trade deficits.

Sorry, but there simply is no validity to your claim that trade deficits have ANY connection to a currency's purchasing power. That is solely dictated by the relevant government's monetary policy...

"Prettiest horse in the glue factory"

I call dibs for band name.

"First: Navarro is only half-right when he says that imports don't contribute to gross domestic product, and he's fully wrong to imply that imports harm growth. (In fact, they don't influence the calculation of GDP at all, but they do have a positive correlation with economic growth.) Second: Running a trade deficit or a trade surplus has virtually no bearing on how quickly a country's economy grows."

From where I'm sitting, the biggest fallacy here may be equivocation.

Sometimes "growth" looks like it's being used to describe economic growth and sometimes "growth" looks like it's being used to describe job growth.

There is nothing wrong with the argument that tariffs could cause labor demand to grow in the short term. Whether extremely low unemployment and increasing wages due to artificial trade barriers are good for economic growth over the long term is another question entirely.

This is the same kind of argument we have over things like minimum wage laws and stimulus spending.

It is wrong to argue that minimum wage laws don't increase wages for low skilled workers in the short term--if it's implemented amid a rapidly growing economy. What happens over the longer term, when unskilled workers are locked out of jobs they'd get if it weren't for the laws making wages so high, is another question entirely.

Stimulus spending does increase employment over the short term. Why wouldn't it? Whether those jobs are desirable or sustainable--or a drag on real economic growth over the long term--is another question entirely.

Regardless, criticizing Navarro for saying wrong things about economic growth--when he may be talking about jobs growth in the shorter term--is getting it wrong. Also, if Navarro is pretending to talk about economic growth by way of the domestic economy when he's really just talking about jobs growth, that is also getting it wrong.

P.S. Wage inflation can be a serious problem for an industry and an economy. The reason the City of Detroit once asked the military to come in and use their city for target practice--to destroy all those uninhabited homes and take the pressure off their police and fire departments--was not because of trade with China. It was largely because workers in the auto industry were way overpaid for far too long by a union that tried to monopolize the access of labor to the auto industry.

What I see is Trump lower income taxes and increasing tariffs under the assumption income taxes are always bad and tariffs have the slight positive of increasing domestic employment. Lesser of 2 evils?

You don't see Trump clearly then. He's an ignorant, protectionist loon...

No doubt, and you forgot thin-skinned egotist, but given Sophie's choice between an income tax and a tariff, I'll take a tariff. I'm hoping he shames Congress into taking on the deficit/debt next but there's no glamour in that.

Whether or not a trade deficit hurts an economy depends on the type of economy and who you're talking about hurting. A deficit or surplus itself doesn't cause anything, but the underlying causes do. Deficits occur in net importing countries and surpluses in net exporting countries. Countries like Japan have large trade surpluses because they export more than they import. Were Japan to have a smaller surplus or a deficit, that would indicate that net imports were greater than net exports. That's bad when your economy is export based. Such a condition could result from relative deflation (this is why Japan does QE and keeps the yen weak against foreign currencies).

America acts like a net importer, but that's why our economy was lagging before Trump. We are not the kind of small, white collar, service-based, hyper wealthy country that people think we are. America is massive and most people, while relatively better off, are not white collar. Many jobs in the US depend on exporting, typically for the lower and middle classes. Plus we continue to import millions of low-skilled illegals on top of our existing problems, namely with minority populations.

This is an oversimplification, but the US is top heavy. White collar workers are doing well, but everyone else suffers from a strong dollar and inability to compete on the global stage. Contrary to what many libertarians and economists say, this isn't their own fault. Government has just as much a role to play with central banking and currency manipulation as the market does. A bit of protectionism and some scraps for the lower classes, while academically inefficient, transfers welfare from foreign exporters to domestic producers who, in turn, spend in their local economies, unlike the Chinese who spend everything in China.

Like Trump so often says, I'm not blaming China. They would be stupid to fly to our small towns to frequent local businesses. That's why we need some national-level redistribution.

Socialist crappola...

Trump is a very stable genius with a very good brain and he attended Wharton* so I'll trust him rather than several centuries of economic theory.

*Or so he says, but he refuses to release his transcripts. Or his birth certificate. Still, Trump has demonstrated the unique ability to look at a problem for 15 or 20 seconds and become the world's foremost expert on that subject so I'm sure he knows more than all the economics textbooks in the world.

Which is why I posted about his statements about steam catapults versus the new electromagnetic ones, he calls them “digital”, when he visited the aircraft carrier the other day. He hears something or gets an idea in his head and that is it.

"I’m sure he knows more than all the economics textbooks in the world" -- Ya know what is super sad. That's probably entirely true. Reality has been debunking the "Bookies" textbook for the last decade.

Adam Smith is on Trump's side on both retaliatory tariffs and the desirability of tariffs to offset taxes on local production.

Adam Smith on Retaliatory tariffs as a negotiating tactic.

"There may be good policy in retaliations of this kind, when there is a probability that they will procure the repeal of the high duties or prohibitions complained of. The recovery of a great foreign market will generally more than compensate the transitory inconveniency of paying dearer during a short time for some sorts of goods. To judge whether such retaliations are likely to produce such an effect, does not, perhaps, belong so much to the science of a legislator, whose deliberations ought to be governed by general principles, which are always the same, as to the skill of that insidious and crafty animal vulgarly called a statesman or politician, whose councils are directed by the momentary fluctuations of affairs."

Adam Smith on tariffs to offset local taxes on production:

"It will generally be advantageous to lay some burden upon foreign industry for the encouragement of domestic industry, when some tax is imposed at home upon the produce of the latter. In this case, it seems reasonable that an equal tax should be imposed upon the like produce of the former. This would not give the monopoly of the borne market to domestic industry, nor turn towards a particular employment a greater share of the stock and labour of the country, than what would naturally go to it. It would only hinder any part of what would naturally go to it from being turned away by the tax into a less natural direction, and would leave the competition between foreign and domestic industry, after the tax, as nearly as possible upon the same footing as before it."

+1 🙂

[…] Peter Navarro, Trump’s top trade advisor, argued in a recent Wall Street Journal op-ed that lowering America’s trade deficit would boost growth. In fact, no such correlation seems to exist for other countries around the world. As I’ve previously written: […]

[…] Peter Navarro, Trump’s top trade advisor, argued in a recent Wall Street Journal op-ed that lowering America’s trade deficit would boost growth. In fact, no such correlation seems to exist for other countries around the world. As I’ve previously written: […]